- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As contemporary author fan bases go, Margaret Atwood’s must be among the broadest. She is read at crèches, on university campuses, and in nursing homes. Feminists, birders, and would-be writers jostle to see her perform at literary festivals. Yet despite an Arthur C. Clarke Award and, in her own words ...

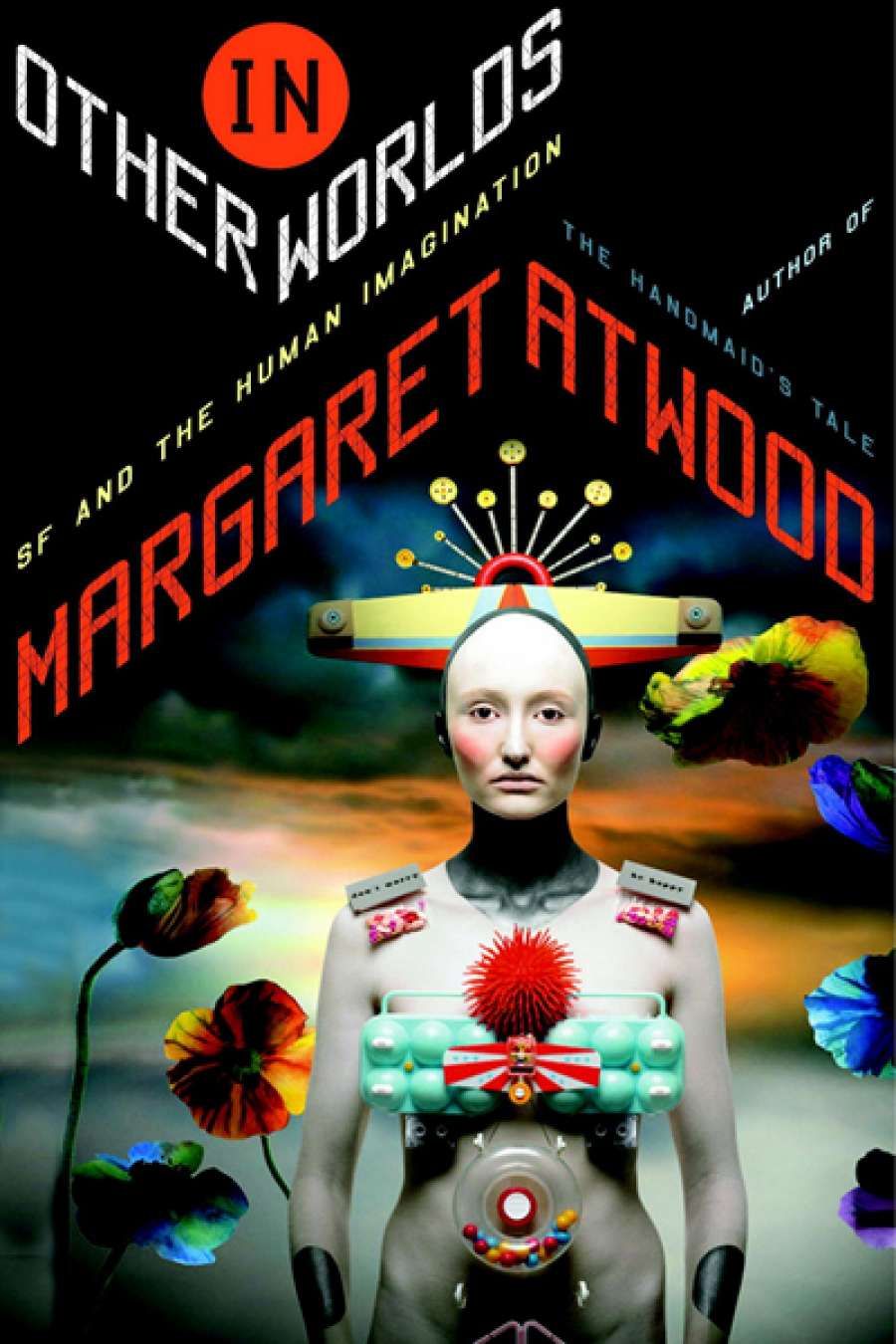

- Book 1 Title: In Other Worlds

- Book 1 Subtitle: SF and the Human Imagination

- Book 1 Biblio: Virago, $40 hb, 272 pp, 9781844087112

As in any serious relationship turned sour, the fault lies on both sides. Atwood’s attitude toward science fiction has always been what could be best described as squeamish. She has steadfastly repudiated attempts to have The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), Oryx and Crake (2003), and The Year of the Flood (2009) thus categorised. Matters came to a head during an interview on BBC1 Breakfast in 2003 when she appeared to dismiss the genre entirely by synopsising it as ‘talking squids in outer space’. While science fiction fans didn’t baulk too much at the description, they did resent the condescension. Few writers of recognised literary merit – let alone women writers – have tried their hand at the oft-maligned genre (Nobel Prize winner Doris Lessing is a notable and rare exception).

‘Atwood’s attitude toward science fiction has always been what could be best described as squeamish’

It is in this context that In Other Worlds can be understood as a kind of olive branch. There is little dodging of the SF label – it is, pointedly, there in the subtitle. The book collects Atwood’s lectures, short stories, essays, introductions, and reviews on science fiction topics from 1976 to 2011, testifying to what she now admits has been a ‘lifelong relationship with [the] literary form, or forms, or subforms, both as reader and as writer’. The key documents of rapprochement are Atwood’s three Richard Ellmann Lectures, which were originally presented at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, in October 2010 and make up the first one hundred pages. The provocation for the volte-face on science fiction appears to have been Ursula K. Le Guin’s 2009 Guardian review of The Year of the Flood, from which Atwood quotes expansively in her introduction. In it Le Guin accuses her of literary toadyism, of complying with the prejudices of ‘hidebound readers, reviewers and prize-awarders’, and of putting the lure of accolades before the obligation of advocacy by renunciating genre. Stung by the charge, Atwood has been actuated to come clean on her indebtedness to science fiction and to make claims for its seriousness.

As is often the case with apologies, Atwood’s comes with a smidgen of self-justification. Those exceedingly slippery things – words and their meanings – are to blame. For more than twenty years Atwood has preferred the term ‘speculative fiction’ instead of ‘science fiction’ to describe her work in order to distinguish between narratives ‘about things that could really happen’ and stories with martians in them. The more latitudinarian Le Guin thinks that it is all science fiction, with the term ‘fantasy’ there to deal with the genre’s more preposterous outer reaches. Atwood has always been fascinated with Queen Bee female figures: it is revealed in this book that she began a PhD in English Literature at Harvard in the early 1960s examining them; having abandoned studies for a writing life, she has done a pretty good job of turning herself into one (see any recent author photograph and meet a white witch or dowager). It takes the say-so of someone of Le Guin’s standing – Atwood calls her science fiction’s ‘reigning monarch’ – to accept finally that she has been writing science fiction all along. In Other Worlds is dedicated to her.

On closer inspection, however, the conciliatory embrace of science fiction only goes so far. Atwood is at pains to shake off the snooty tag and parade her egalitarian and eclectic reading habits in the Ellmann Lectures in particular. She tells us that at nine or ten she was devouring ‘anything that was handy, including cereal boxes, washroom graffiti, Reader’s Digests, magazine advertisements, rainy-day hobby books, billboards, and trashy pulps’. At high school she lived ‘a double life’, reading Shakespeare in the classroom but Donovan’s Brain after the final bell sounded. Then at Harvard, the Lamont Library and its Woodberry Poetry Room denied to her because of her gender, she compensated with the stacks of the Widener Library and the ‘sidebars of literary history’ there contained. But for all of Atwood’s sometimes unwitting, othertimes wilful disregard of the canon and notions of literary value as a reader, In Other Worlds reveals that her engagement with science fiction as a writer has been almost exclusively high-end: H. Rider Haggard’s She: A History of Adventure, H. G. Wells’s The Island of Dr Moreau, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. No talking squids from outer space here; indeed, there is virtually no mention of authors working in the period following science fiction’s so-called Golden Age, except in passing. To paraphrase George Orwell’s Animal Farm, which Atwood tells us she read aged nine, taking it for ‘a book about talking animals, sort of like The Wind in the Willows’, ‘All Science Fiction Books Are Equal, but Some Are More Equal Than Others.’

‘But for all of Atwood’s sometimes unwitting, othertimes wilful disregard of the canon and notions of literary value as a reader, In Other Worlds reveals that her engagement with science fiction as a writer has been almost exclusively high-end’

It is up to the Ellmann Lectures to correct this bias, and, with passing references to Batman, B-movies, and William Gibson, big claims are made for the genre, generally. These claims turn on a series of paradoxes, which isn’t so surprising given that there is one of sorts inherent in the term ‘science fiction’ itself. First, Atwood speculates that non-naturalistic narratives might be our most natural mode of expression. Exhibit A is her own juvenilia, a series of drawings and tales about the adventures of two flying rabbits in a place called Mischiefland. While Atwood acknowledges the inspiration of her older brother’s Bunnyland, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, and the family home’s one small book on the solar system, she maintains that her attraction to the fantastic in early life was born of an essential human tendency, one that separates us from the animals: an awareness of here and there, and a curiosity about other worlds.

The second paradox Atwood pursues is that science fiction, so often conceived as a genre of the future, is actually a living trace of our past, ‘hav[ing] deep roots in literary and cultural history, and possibly in the human psyche’. Wonder Woman is a modern-day Artemis, and caped crusaders are just angels in disguise. Science fiction is where myth and religion have gone to survive. All ask the same fundamental questions, such as: Where did the world come from? Why do bad things happen to good people? What is right behaviour? The final paradox Atwood treats is that science fiction permits us a more real engagement with the world than realism. The Handmaid’s Tale, she explains, was prompted by time spent living in real-world ‘ustopias’, her term for places that act on utopian intents but result in dystopian effects: East Berlin, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and (tongue firmly in cheek) Alabama. Science fiction is the best vehicle, she maintains, to ruminate upon the current challenges that fundamentalism, environmental catastrophe, and economic collapse are laying down to Western-style liberal democracies.

As literary critic, Atwood makes for lively company. Like the perfect dinner party guest, she is informative but never ponderous, intimate in a way that never gets too deep. She does not, on final account, rank among those writers – Virginia Woolf, Samuel Beckett, Martin Amis – whose occasional criticism of other people’s writing dazzles and challenges us to new interpretations. But it is in her decision to cosy up to and never alienate readers unfamiliar with the literature she discusses that she, conclusively, casts off the imputations of snobbery.

Comments powered by CComment