- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

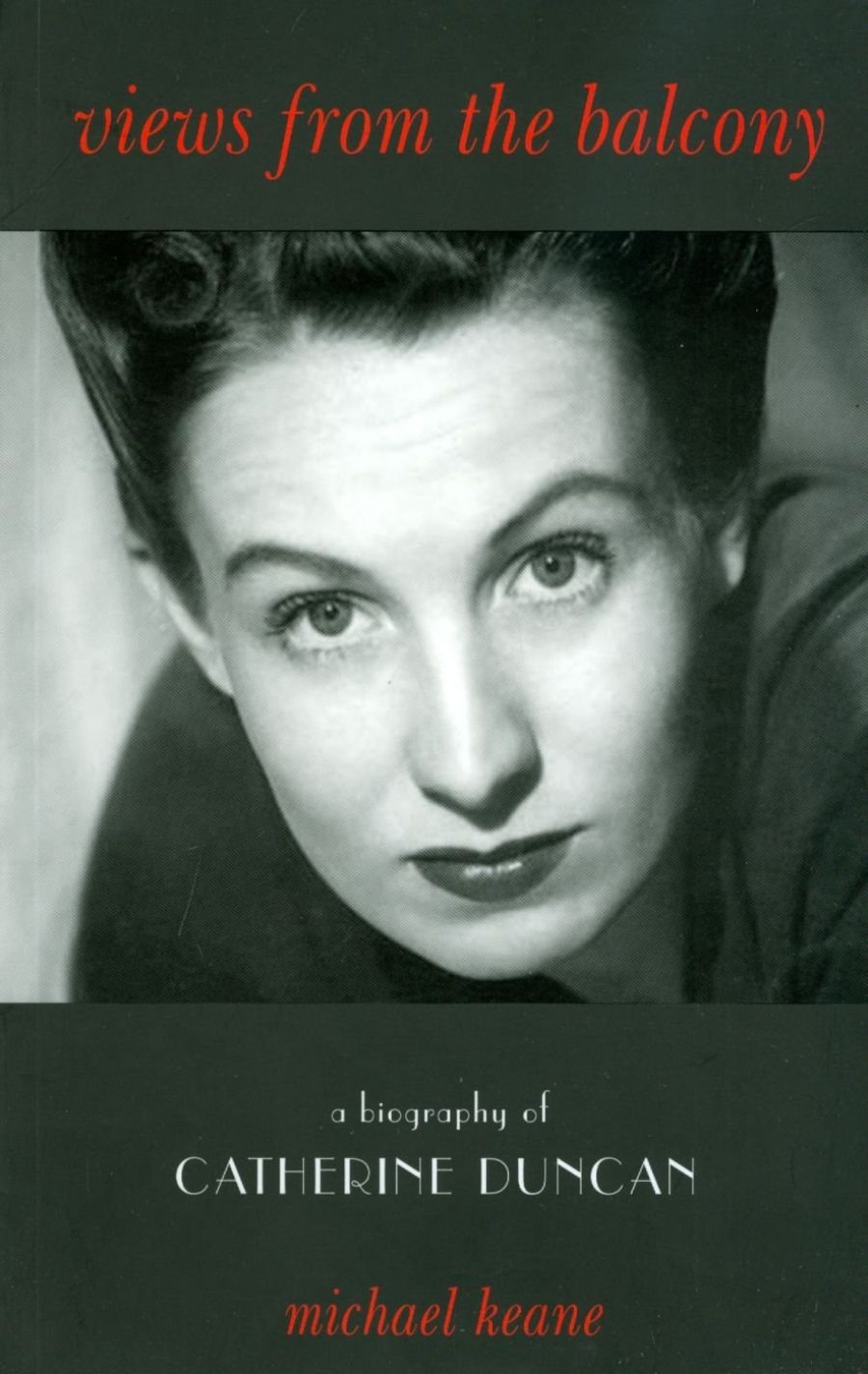

Catherine Duncan looks like becoming the poster girl for Australian women playwrights of the 1930s and 1940s. Her sleek, sophisticated face – the epitome of the 1940s career woman – looked out from the cover of Michelle Arrow’s Upstaged: Australian Women Dramatists in the Limelight at Last (2002), and now it graces the cover of Views from the Balcony: A Biography of Catherine Duncan, written by her son, Michael Keane.

- Book 1 Title: Views From The Balcony

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Biography of Catherine Duncan

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan Art Publishing, $39.95 pb, 224 pp

Duncan is one of a number of women writers from what has been considered a fallow period between the late 1920s and the 1960s whose careers have been restored to public notice, notably by Arrow and by Susan Sheridan in Nine Lives: Postwar Women Writers Making Their Mark (2011). These women wrote for the theatre, for the ABC and commercial radio, for the Women’s Weekly, for little magazines, and later for television, some also being aspiring novelists and poets. Many lived unconventional lives as they tried to work out how to combine love, work, and families. Professional women such as Roma Mitchell (in Susan Magarey’s biography, 2007) and Frank Moorhouse’s fictional internationalist Edith Campbell Berry faced similar dilemmas.

Catherine Duncan (1915–2006) was one of the women playwrights who dominated a period remarkable for its encouragement of local writing. In 1938 her anti-war play The Sword Sung won the playwriting competition of the New Theatre League, a communist organisation to which she belonged and which gave zest to Melbourne’s theatre world in the 1930s. This success launched her busy acting and writing career in radio. Her play Sons of the Morning, first broadcast as part of commercial producer John Hinkling’s Living Theatre, won the 1945 Playwrights’ Advisory Board competition. The following year, she and Peter Finch received the first Macquarie Awards for the best female and male actors. Radio historian Richard Lane considered that Duncan’s was the most exceptional career of any Australian woman of the period: ‘There have been better actresses, perhaps better writers, but no one who combined the two … with such verve, wit, and lively intelligence.’

In 1945 Duncan joined the newly formed Australian National Film Board, first as writer then as director, bringing documentary pioneer John Grierson’s ideas on the social purpose of film to bear on Australian themes. This led her to work with Dutch documentary film-maker Joris Ivens, on his now-classic Indonesia Calling (1946), for which she wrote the commentary.

Duncan recalled how the New Theatre had introduced her to ‘a yeasty mixture of art and politics that burst the seams of prosaic living’ and encouraged her to think of herself, like Edith Campbell Berry, as a ‘world citizen’. This exhilarating atmosphere stimulated not only the determined pursuit of a career wherever it may take her, but also the search for sexual happiness. Her marriage to foreign correspondent Kim Keane evaporated in the face of his frequent absences and her long affair with commentator Peter Russo (who ended their relationship with a telegram informing her of his marriage). In 1947, inspired by Ivens and lured by the possibility of a job with the BBC, she set off for Europe on a ship bound for Marseilles. She fell in love with the captain and settled with him in Paris, where she remained for the rest of her long life. Although she stayed active creatively, that was essentially the end of her professional career.

When Duncan embarked for Marseilles she left her two children, Michael, aged eight, and Margherita, aged four, in the care of her parents. Kim Keane left at the same time to begin a new marriage and career in New Zealand, and the children never saw him again. This seems incredibly callous to us. But this was a period when women thought it impossible to combine love, work, and family. Doris Lessing did the same in 1949; and P.D. James sent her three-year-old daughter to boarding school when her invalid husband returned from the war and she had to earn a living.

Michael Keane seems to have emerged from what he describes as a miserable childhood with no bitterness towards his mother. This biography is not an exploration of any wounds that childhood may have inflicted. Instead, it is an admiring portrait of an unusual and talented mother with whom he appears to have had an affectionate relationship in his adult years.

Keane’s book might have been more interesting, however, if he had included more about his own feelings. He draws on his mother’s extensive writing and letters (now in the State Library of Victoria) to tell her story, but without the historian’s or literary biographer’s skills to place that story in its context or to evaluate her place in Australian literary history. As it is, the book’s main virtues are that it alerts us to the existence of interesting new material and gives us a sense of the full arc of Duncan’s life. What I longed for was what only a son can tell us – what she meant to him, what his grandparents were like, what they thought of her desertion of her children, what his relationship with his sister was like. These things would tell us much about the expectations women faced in this betwixt-and-between period after the feminism of the early twentieth century and before that of the 1960s and 1970s. Ultimately, that is what Catherine Duncan’s story is about: the difficulties of being a career woman, a mother, and a lover in a period of indecision about women’s roles. Keane’s book gives us enticing glimmers of that story.

Comments powered by CComment