- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

My Brilliant Career, the book Miles Franklin published in 1901 when she was twenty-one, cast a shadow over her entire life. It sold well and made her famous for a time, but it did not lead to the publication of more works. The glittering literary career foretold by the critics did not eventuate, at least in Franklin’s opinion. ‘The thing that puzzles me,’ she wrote to Mary Fullerton on New Year’s Day, 1929, ‘is how are we to know whether we are a dud or not at the beginning; I mean how long should a poor creature smitten with the egotism that he can write, keep on in face of rebuffs’.

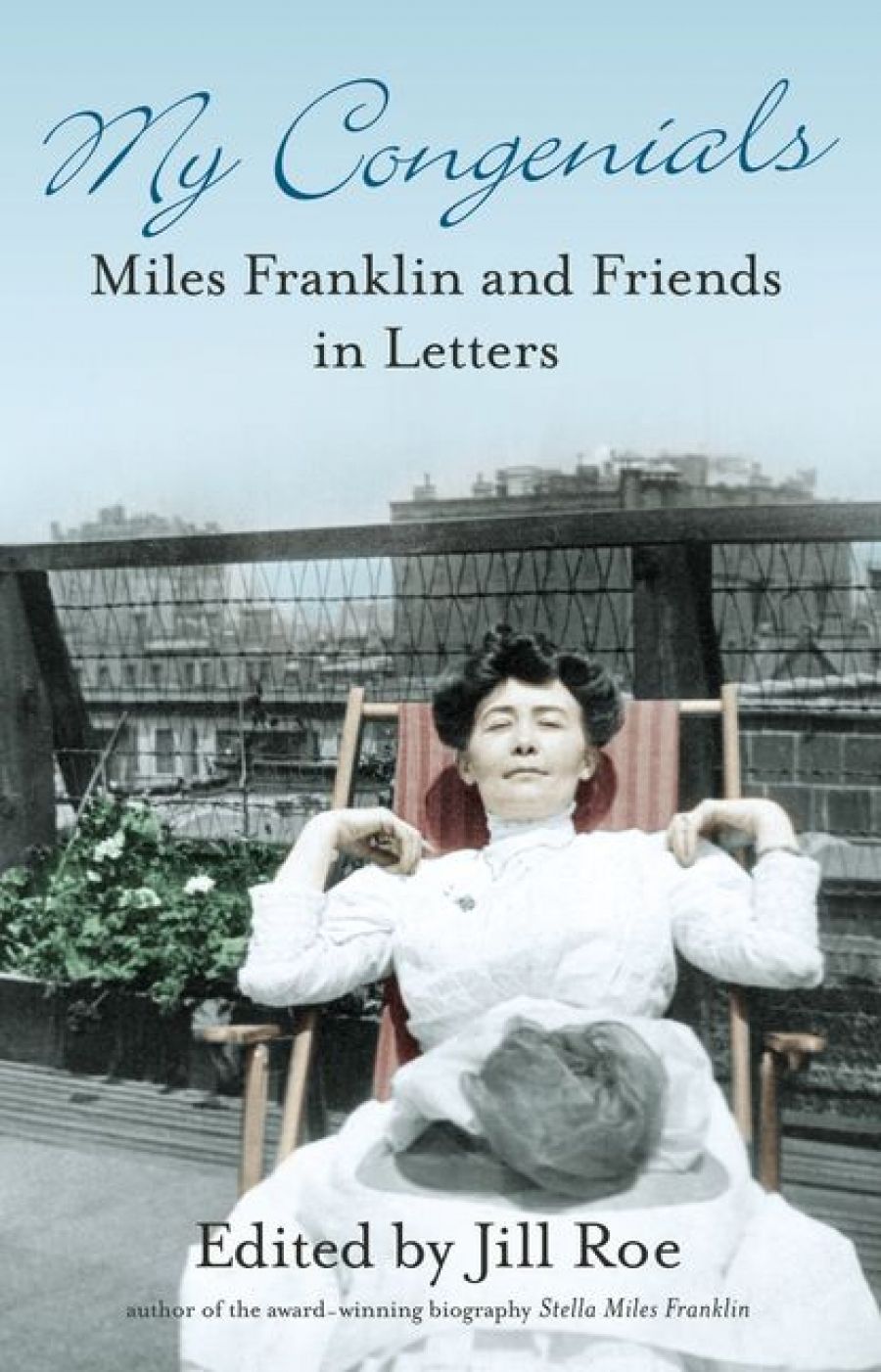

- Book 1 Title: My Congenials

- Book 1 Subtitle: Miles Franklin and friends in letters

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins, $35 pb, 832 pp

In 1932 she returned to Australia, publishing All That Swagger in 1936. It was My Brilliant Career all over again, but more financially rewarding. She received good reviews and hundreds of fan letters, one of which said she was as exciting as Don Bradman. The book was broadcast on the wireless and reprinted regularly during Franklin’s lifetime. It was too late. A subsequent string of publications right up to the year of her death could not change that. Nothing would convince her that she was not a literary failure.

Franklin’s letters throughout her life are testimony to this feeling of rejection. In 1919 she told Alice Henry: ‘But I’ll be dead some day with nothing but a miserable little bit of uncomfortable life behind. I hope this is the purgatory of the Catholic faith and something better will come later.’ In 1941 she wrote to Eleanor Dark: ‘The buckram has gone out of me. I sometimes think I am dead but still walk around. I am paralysed by desolation.’ In the month of her death, she wrote to Marjorie Pizer: ‘I have never gained self-confidence & my writing fills me with a sense of tortured failure. Critics don’t see the underside or innerness of what I attempt.’

The point, though, was that Franklin never did give up. She had told Joseph Furphy as far back as 1904: ‘a phrenologist gave his opinion that I couldn’t be crushed, because I could never be brought to accept defeat as final’. ‘I bewilder myself, I’m so complex,’ she wrote to Emma Pischel in May 1947, ‘so how could he who knows me not, be able to unravel me?’ These letters help with the unravelling. While they document the lifelong fears of a wasted life, they also document an extraordinarily varied and adventurous one and demonstrate what all her contemporaries recognised – her vibrant, life-enhancing personality.

In Chicago, she undertook pioneering and important work for the National Women’s Trade Union League with a group of talented women who remained friends and correspondents. ‘I love my work very much as it brings me in to close friendship with everyone in the world who is making thought and history,’ she wrote to her aunt, Annie Franklin, in 1913. These years were also very active socially: singing lessons, piano lessons, French lessons, lunches, dinners, dancing, the opera, concerts, theatres, learning to drive an automobile. There were a number of eligible young men – as there always had been and would be. Franklin’s sister, Linda, wrote to her just after her departure from Australia in 1906: ‘You bad girl to leave such a lot of broken hearts behind. To be hoped you won’t break so many in America, if so stay with one of them & console the poor thing.’

Franklin was forever attractive to men – that combination of indomitability, sensitivity, and vulnerability is lethal. In 1943 she wrote to Dymphna Cusack:

I recently went into a great trunk and destroyed scores of letters. One dear old friend went around telling everyone how I had refused him. I used to argue that he had never really proposed. Had entirely forgotten; but there among the letters were his very definite proposals; not only from him but from others I had similarly forgotten. A Senator from another state called me up some months ago and asked me had I forgotten his proposal to me on board the ship when I first left Australia. I’m sure he never proposed, but he swore he had done so. So I said flippantly, ‘Are you proposing again now?’ He said, ‘Yes, if you are the same radiant creature that I knew’. ‘Don’t be an ass,’ I replied; ‘how radiant would you be after thirty years?’ I’m sure this man never proposed to me, but I think he imagines he did. I think that when a girl is the rage lots of men who have never said a love word to her imagine they have had great sentimental sessions …

In Britain, Franklin worked as Secretary with the National Housing and Town Planning Association and organised a women’s international housing conference in 1924. She enjoyed the cultural offerings of the great imperial capital. As she wrote to Mary Fullerton in 1934: ‘Times do eat into us but we had those lovely days of inspiration and association and the feasts of culture provided by old London and they cannot be taken from us.’

Back in Australia, she plunged into the literary scene with gusto and, such was the force of her personality, it was as if she had never been away. She spoke up for literature that was distinctively Australian. She wrote to the Prime Minister Ben Chifley in 1945:

Without a literature of our own we are dumb. In the disturbed world of today more than ever we need that interpretation of ourselves, both to the outside world and to ourselves, which is the special function of imaginative writers.

She was known for her sparkling wit and keen powers of observation. Jean Devanny wrote to Franklin in 1952: ‘That’s your trademark – a brilliant whimsical originality.’ And Katharine Susannah Prichard wrote the following year: ‘Such a treat just to hear you talk. I do love the wit & play of your so original mind. Nobody makes me laugh so much … so delightfully Miles, gay, intrepid & unique!’

Jill Roe has edited this collection superbly, providing contextual information about Franklin and all her congenials. She has selected 486 letters (out of approximately 10,000) by and to Franklin, covering the years from 1887, when Franklin was seven, until her death, aged seventy-four, in 1954.

I have only two criticisms. It is a pity that none of the letters Franklin wrote to the publisher William Blackwood in the recently discovered publisher’s file were included. These cast fresh light on Franklin’s use of the Brent of Bin Bin pseudonym. My second criticism is the production itself – poor paper, and illustrations that lack clarity. This really is not good enough, Angus & Robertson. ‘You rejected my first book and now 110 years later you dress me in sackcloth and ashes’, I hear Miles saying.

However, as Franklin wrote to Margaret Dreier Robins in November 1930 in relation to her lack of modish dress: ‘my friends who are ashamed of the look of me can see me behind closed doors.’ When we plunge, behind closed doors, into what Roe rightly calls this ‘sample of riches’, we forget the packaging. In July 1929 Franklin wrote to Nettie Palmer: ‘I am happy that you consider I have achieved “Communicable delight”.’ And that is just what this volume is – communicable delight.

Comments powered by CComment