- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Few who saw them will forget the grainy newspaper images of Australian drug traffickers Kevin Barlow and Brian Chambers. Despite high-level diplomatic pleas from the Australian government, they were hanged at Pudu jail in Kuala Lumpur in July 1986 for possessing 180 grams of heroin. In the post-execution mêlée, their bodies were concealed by blankets, but one foot was casually left uncovered. The poignancy of those toes was heart-rending, their vulnerability encapsulating the brutal and ruthless efficiency of law in that region of South-East Asia.

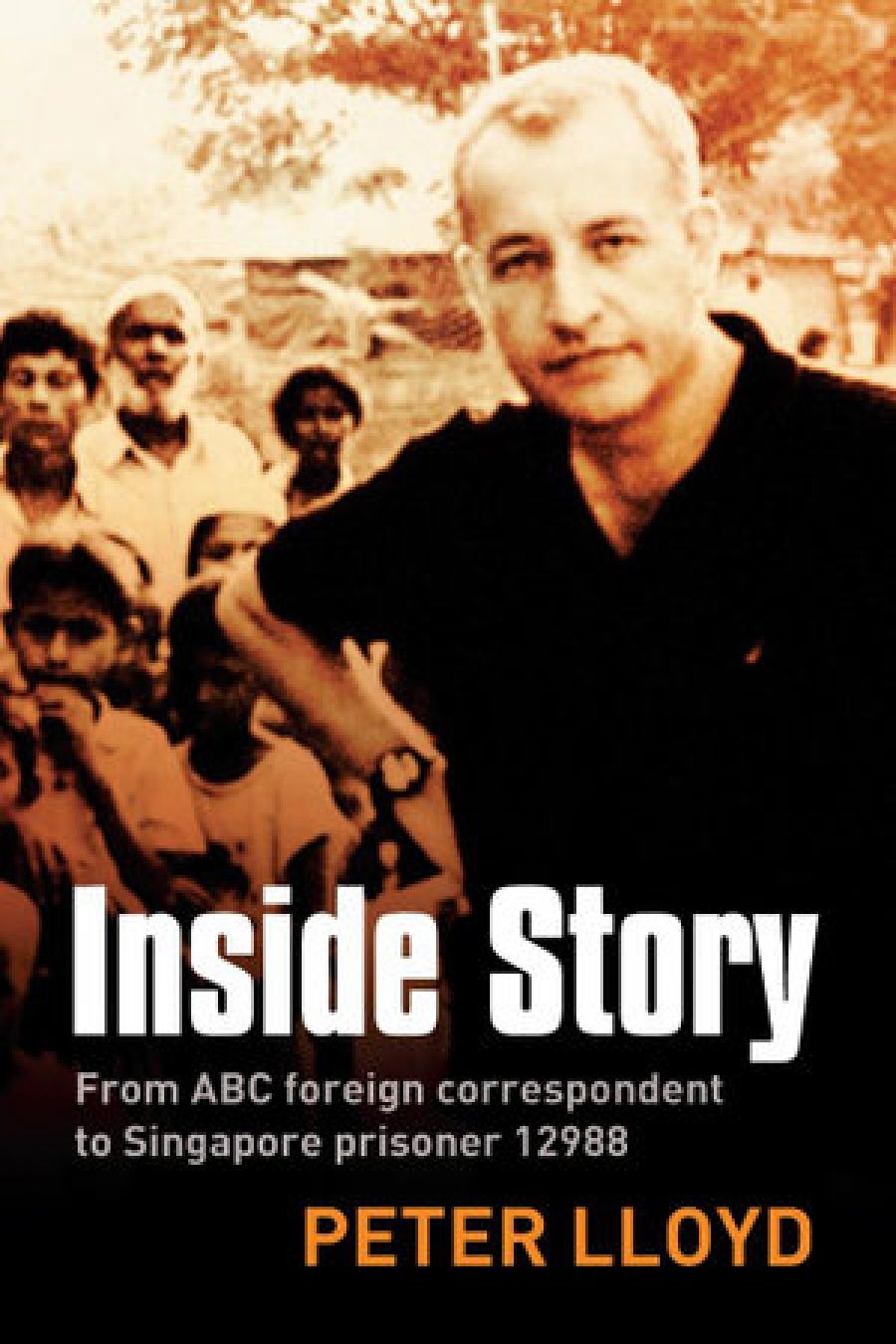

- Book 1 Title: Inside Story

- Book 1 Subtitle: From ABC correspondent to Singapore prisoner #12988

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $35 pb, 296 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/rZnjj

Over the past decade, Singapore has been keen to promote a gentler global image of itself as a modern, ‘can do’ business/leisure hub, and Westerners have generally escaped the worst excesses of its punitive practices, although that clemency cannot be taken for granted. So it is not hard to imagine the panic that overwhelmed Australian television journalist Peter Lloyd when he was confronted in the streets of Singapore by a posse of undercover police, accused of trafficking in methamphetamine, or ‘ice’, and dragged away in handcuffs. There was a Kafkaesque element to his situation as he learned he had been fingered by a passing acquaintance and faced a minimum five years’ jail and five lashes.

Lloyd, an accidental tourist to the island, was on a flying visit from his base in India to have medical treatment. But he was, by his own admission, not well in more serious ways. The calm control he displayed in his prominent career as a foreign correspondent for ABC Television had become a brittle veneer for a man on the edge of mental collapse. In the previous decade, he had covered both Bali bombings, the earthquake/tsunami in South-East Asia, bombings in Jakarta, the Karachi bombing of Benazir Bhutto’s retinue and the Afghan war. There was an emotional toll to reporting dispassionately on tragedy and witnessing charnel-house displays of blood, dismembered bodies and horrific injuries. Lloyd began to buckle under what he called the relentless demands of being a one-man South Asia foreign correspondent office in a network whose appetite for news content was growing. By the time he was dispatched to Pakistan for post-Benazir elections,

I was pretty jumpy about being blown up ... we had to limit the amount of time we spent on the street because we were worried about suicide attacks. I was smoking two packets a day, and sleeping with the curtains drawn all the time. I was certain the windows were going to explode.

This was not the same man who, as a novice covering the first Bali bombing, had discovered the power of adrenalin charging around the body and that ‘disaster focuses my mind. Under ridiculous pressure, I manage to organise, prioritise and respond to work-crazy demands with, mostly, good humour.’

His ambivalent response to Bhutto’s assassination marked his descent: on the day she was killed, he was flying to New Delhi.

I sat with a copy of the newspaper reporting her death in my lap. Above the fold was a huge and flatteringly beautiful photograph of the woman who had so fascinated and frustrated me. For two hours I sat and cried. Once I started weeping, I could not stop.

He had, during his time on the frontline, undergone considerable life changes. He had left his wife and two children on realising that he was gay, he was existing in a rarefied atmosphere of dangerous events and country-hopping, mixing with both the power élite and the socially distraught. He was on an emotional rollercoaster accelerating out of control, self-medicating with drugs and drink. He was sleep-deprived, and even when exhaustion knocked him out, he had recurring nightmares of cinematic intensity and unbearable clarity. What happened in Singapore, he writes, ‘was a perfect storm of circumstances: I was on an unscheduled visit and unwell. I acted unwisely. I made a huge mistake.’

It was a mistake seized on by many of his erstwhile colleagues, generating glaring headlines and some Schadenfreude. The repercussions were personally and professionally devastating. It was, he says with commendable understatement, a horror movie that seemed at every turn to become more horrendous. He had been set up, but he was a big catch for the self-righteous system, an opportunity to parade its ‘no one is exempt’ message.

Singapore, he says, is what happens when a lawyer with a narcissistic need for absolute control invents a country. Citizens’ rights are a platitude rather than a reality.

Lloyd had not long before begun a relationship with a Singapore-based Malay airline steward, and was racked with guilt over subjecting their nascent bond to such stress. He worried that he had exposed his very proper partner as a member of a minority ‘in an intolerant, deeply conservative Chinese community. The people who run this place have a long memory, and they are good haters.’

It was only after his release on hard-won bail that Lloyd began to have therapy and to realise how traumatised he had become. There is a high attrition rate among foreign correspondents who cover the tragedy trail: one in six suffers extreme post-traumatic stress disorder, and many have to leave their careers permanently.

Over months of waiting for trial, Lloyd worked to heal himself, while trying desperately to hold himself together as lawyers negotiated down the worst-case scenario to something almost bearable. Eventually, in the ‘no escape’ environment that is the Singaporean justice system, he pleaded guilty to charges that carry ten months’ jail, which, with good behaviour and remissions, was reduced to 200 days.

Anywhere else in the world I would fight these charges, pleading for mercy and commonsense. But with no jury to plead to and a conveyor-belt one-size-fits-all legal system, winning is impossible ... Singapore’s criminal judges work off a printed sentencing schedule, handed down by the higher courts ... it is impossible for a lower court judge to circumvent the system of predetermined sentences and exercise independent-minded judgement.

Jail, while no picnic, was not the inferno of his imaginings. Before long, he was made a ‘cookie’, the junior member of a trusted detail that dispensed food to their cellmates. This brought privileges: $1.50 pay a week, selected non-political television viewing and ten hours a day out of his tiny cell. He read incessantly, ran endless laps of the exercise yard when given access, wrote a diary, generally kept his nose as clean as possible, made superficial friendships and reassessed his values.

I am under constant human and video surveillance. I find that reassuring. Prisoners cannot get away with anything untoward but nor can officers; we are mutually accountable for our actions. Singapore prisons are probably cleaner and safer and more secure for prisoners than many penal institutions around the world.

When he was released from jail, Lloyd was determined not to look back – and he hasn’t. In many ways, despite its intimacy, his memoir is of a similar mien. For all its facility and apparent confidences, it is no deep trawl into the mind of the man. It is honest, as far as it goes, and written with pace and some style, as befits a journalist of Lloyd’s standing, but it is more imminent than eminent.

In the end, there is a Boy’s Own gloss to the tale that leaves more than the odd question unanswered. In all writing, what is left out is more important than what survives the inner censor, and Lloyd is a little like the magician who focuses attention in desired misdirections to obscure the real legerdemain. His back-story is mostly noticeable by its absence, and the breathless emphasis on the debilitations of traumatic stress, while worthy of sympathy and understanding, begins to seem like a concealing rationale. The fears and doubts, and the long nights of the soul during his incarceration, vanish under a doughtiness that reads like the journal of a stiff-upper-lipped schoolboy at boarding school. Which is not, I hope, to demean a cautionary tale written with gusto and guts – it is just that it could have been so much better with less protective coating.

Comments powered by CComment