- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This book is long overdue. It is eighty years since affable Joseph Lyons, often depicted by cartoonists as a koala, was elected as Australia’s tenth prime minister. He would be re-elected twice before dying in office in April 1939. During his seven years as prime minister, Lyons had to grapple with the Depression ...

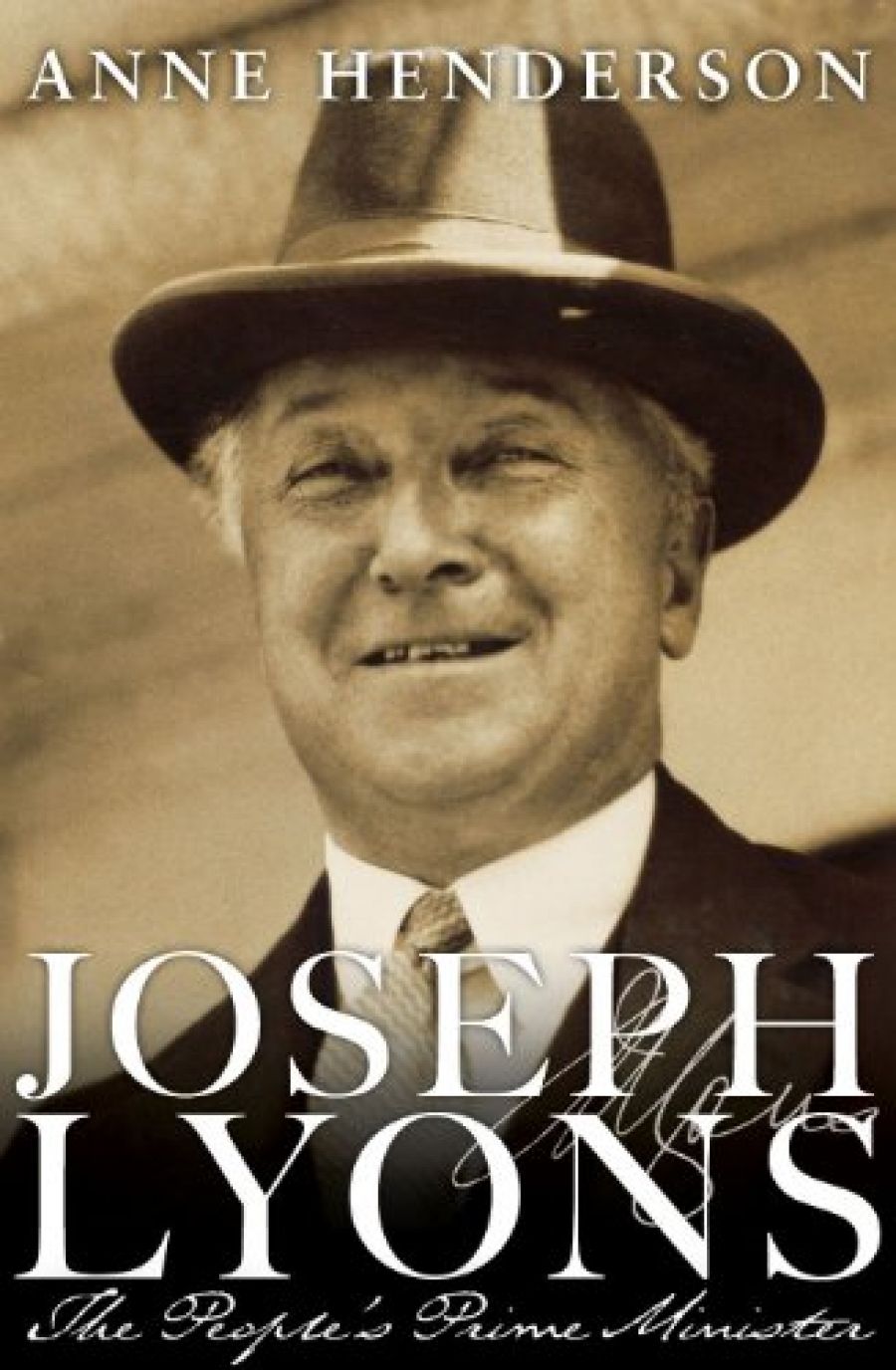

- Book 1 Title: Joseph Lyons: The People’s Prime Minister

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $49.95 hb, 480 pp, 9781742231426

Born in north-west Tasmania to a family that fell on hard times after his father lost his savings on ‘a sure thing’ in the Melbourne Cup, Lyons went from being a low-paid monitor at a small country school in 1894 to being the minister for education in Tasmania’s first Labor government. By 1923 he was premier of Tasmania. Nine years later, leading a new political party, he became prime minister.

Despite his achievements, Lyons holds the curious distinction of being perhaps the only prime minister who is less well known than his partner is. His wife, the formidable Dame Enid Lyons, was elected to parliament in her own right after his death and served as a Liberal MP for eight years, including two years in the cabinet of Robert Menzies. Her stature is reflected by the fact that Anne Henderson wrote Enid’s biography before that of her husband (Ann Moyal reviewed it in the October 2008 issue of ABR).

The pair was certainly a powerful political combination. Despite bearing him eleven children, along with others who were stillborn or died young, Enid accompanied him on many of his campaigns, moved motions at Labor Party conferences, and provided him with sage political advice throughout his life. When he became prime minister, Lyons told Enid that the honour was as much hers as his.

These days, such a career would have been cut short by the nature of his relationship with Enid: Lyons began wooing her when she was a fifteen-year-old student at teachers’ college and he the thirty-five-year-old minister for education. Indeed, it would probably lead to his being imprisoned, and listed for life as a sex offender. Back then, after a passionate (often daily) exchange of love letters, they became engaged when she was seventeen and had converted to his Catholicism.

It is good to see Anne Henderson giving adequate attention to Lyons’s childhood and early political development, a phase often treated cursorily by political biographers. Catholic herself, Henderson brings an understanding touch to the ways in which religion helped shape Lyons and affected, often divisively, the nature of small-town Tasmania.

By having Enid leave the Methodist church for the Catholic one, Lyons stayed true to his own church; it seemed that he would stay true to the Labor Party as well. When the party split over conscription during World War I, Lyons refused to follow Billy Hughes and remained throughout his life a staunch anti-conscriptionist. As premier during the 1920s, he held the party together as it grappled with unpalatable measures to deal with the state’s debt burden. But his attachment to the party was put to its most severe test following his election to federal parliament in 1929.

Lyons’s background as premier saw him propelled straight onto the front bench of James Scullin’s Labor government. It was not a good time to gain power, with the stock market crash of 1929 adding to Australia’s mounting economic problems. A collapse in export prices, combined with an intolerable debt burden, threatened bankruptcy for the country. Lyons, who had surmounted similar economic problems as Tasmanian premier, was inclined to favour traditional responses based on expenditure cutbacks, reducing the value of the Australian pound and dropping interest rates. However, many of his Labor colleagues favoured more radical responses. The most radical response was proposed by New South Wales Labor Premier Jack Lang and his supporters in the federal parliament, who called for Australia to repudiate its interest payments to British lenders. That way, foreign bondholders would be forced to share the pain of the Depression with Australian wage-earners and pensioners. This was anathema to Lyons and other Labor parliamentarians, and caused apoplexy amongst conservatives, bankers, and businessmen. As a nation dependent on foreign investment, such a policy would have damaged Australia for decades.

With radical solutions gaining popularity on the left, and quasi-fascist movements gaining support on the right, it seemed that Australia’s democratic institutions were bereft of solutions to the nation’s economic predicament. More accurately, there were too many irreconcilable solutions and a real danger that decisions would be made on the street rather than in parliament. This is where Lyons earned his place in history by defying the Labor caucus and joining with the conservatives to create the United Australia Party (UAP) in 1931. At the 1932 federal election, the UAP, led by ‘Honest Joe’ Lyons, won a resounding victory.

Lyons is usually portrayed in Labor circles as a weak politician who was seduced by Melbourne businessmen into putting a Labor face on a conservative government. If not heaped with as much opprobrium as Hughes, he is still seen by many Laborites as another Labor ‘rat’. With the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that Labor had become so divided that it had lost the ability to govern effectively or to lead the nation during an economic crisis. By leaving the party, Lyons provided the semblance of a national government, which quickly brought an end to the populist, right-wing rabble-rousing, while Labor’s decade in the wilderness gave time for its divisions to be largely healed and for a strong and effective Labor government to emerge when Australia desperately needed one in 1941.

One of the strengths of Henderson’s biography is the detailed treatment of this climactic episode in Lyons’s life, as he wrestled for weeks with the decision whether to leave the party. He had always vowed that he would put the nation before the party. Australia and the Labor Party should be thankful that he did so. The formation of the UAP, and Australia’s gradual emergence from the Depression under Lyons’s leadership, caused the political rancour to abate and ended the very real risk of fighting in the streets.

Lyons was less able to deal with the political and strategic issues caused by the rise of the totalitarian powers and the threat they posed to the British Empire. His anti-war and anti-conscription inclinations led him to search for ways to ward off another world war, which drove him into the camp of the appeasers. Although Britain was clearly in decline as a world power, Lyons maintained Australia’s commitment to imperial defence long after Labor leader John Curtin had argued its futility and called for Australia to boost its local defences. Lyons’s third successive election victory seemed to vindicate his stance, but the fall of Singapore in 1942 proved that Curtin had been right.

By then, Lyons had been dead for nearly three years. At the time of Lyons’s heart attack, there was rising dissatisfaction with his leadership, with young Robert Menzies among those MPs who were keen to replace him. Lyons only lingered long enough for Enid to reach his Sydney hospital bed from Tasmania. It was a sad ending to the life of a decent politician who contributed much to the making of modern Australia. Henderson’s sympathetic portrayal finally does justice to a leader she likens to Bob Hawke and Paul Keating, a man who ‘spoke the vernacular of the ordinary man and woman, and [who] knew when to compromise the dogmas of the party for the common good’.

Comments powered by CComment