- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

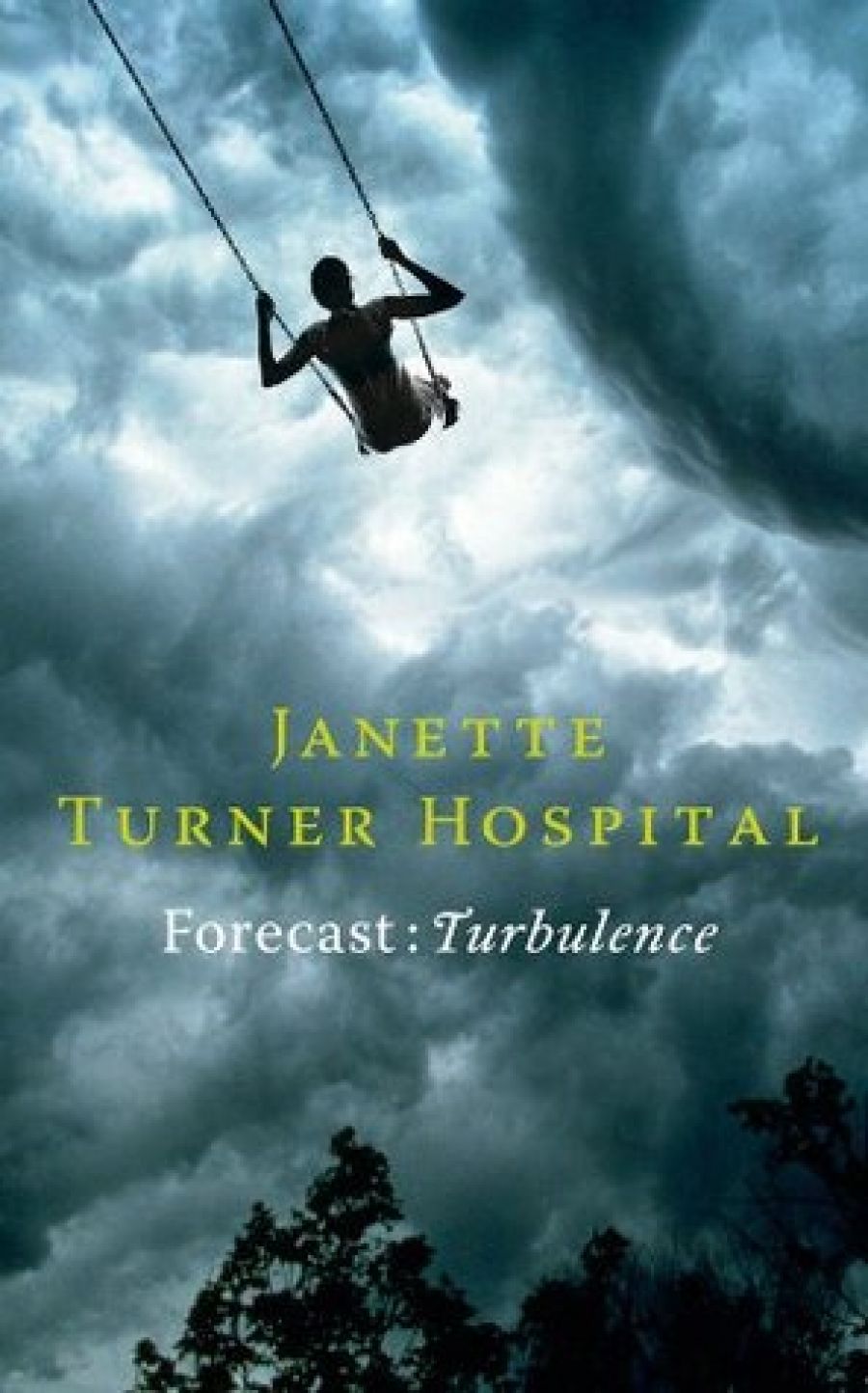

Janette Turner Hospital, who grew up in Brisbane, has taught in Australian and overseas universities, and is well regarded as a novelist and short story writer; among several prizes she has won the Patrick White Award. The stories in her new collection, Forecast: Turbulence, are set in several places where she has lived, including Canada and the American South, where the weather is similarly violent. Despite the fact that this metaphor is flagged throughout this collection, I formed little sense of many of her characters in either place or clime.

- Book 1 Title: Forecast

- Book 1 Subtitle: Turbulence

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $29.99 hb, 232 pp

‘Blind Date’is one of the more successful stories. Tender and ironic in tone, it tells the tale of Lachlan, reunited with his absent father at his sister’s wedding: ‘Lachlan has many conversations with his father [...] “Do you miss me?” “Every single day,” his father says. Sometimes he says that. Sometimes he says: “Who are you?”’ ‘Salvage’, set at the old Tangalooma whaling station off Moreton Bay in Queensland, has a surreal central character with Piscean overtones, while the baroque ‘Republic of Outer Barcoo’ mixes state secessionism Queensland-style with US cultism. Turner Hospital confuses American and Australian phrases, calling jackaroos ‘cow-hands’. Hugh Jackman, Anna Bligh, and semi-automatic rifles get a mention, yet this story feels neither contemporary nor authentic. ‘The Prince of Darkness is a Gentleman’has an elegant title which one of the characters helpfully explains is drawn from King Lear. The point of the narrative arc in this tale of paedophilia is inconclusive. It is yet another story that depicts an absent or unsatisfactory father, a theme that might well have been the more genuine impetus for this collection.

There is a strange uncertainty through this book, and it isn’t the weather. Turner Hospital gives the impression of an unsettled wafting that at one point shows her innate strengths and at another betrays her lack of substance. Though she describes place, she is less adept at creating atmosphere, and her characterisations often remain paper ghosts. She plucks ideas out of the air, but they don’t suffice.

The core premise of any drama is its most vital factor. Alfred Hitchcock called it the ‘McGuffin’, the mysterious element that drives the story forward. If you get the McGuffin wrong (as Christos Tsiolkas did with his eponymous slap), if it’s too contrived or psychologically inconsistent, the audience loses faith in the story’s trajectory. Turner Hospital tries to insert her ‘weather’ McGuffin into her collection in ‘Hurricane Season’: ‘What can never be accurately predicted is the sheer velocity of the sequence from initial disturbance to chaos. Tumult begins without warning and can happen anywhere, anytime, at an airport, a book shop, a dinner party: eye contact, latent heat, a mad buoyancy, increased instability, derangement [...] “You’re wild as a hurricane,” he says. “We have to go wherever this takes us.”’Wild weather for wild emotions, but this device reminds me of the two teenage ghosts in the Ghost Train at the Brisbane ‘Ekka’ – I could see their short black socks and sandshoes beneath their skeleton costumes.

In her most fully realised story, ‘Weather Maps’, where two self-harming girls meet when visiting their respective jailbird fathers, things start well only to slow down under the weight of her tacked-on contrivance: ‘“It’s private weather down here,” she said.’ This pointing up of the weather thread is followed by turgidity: ‘I suppose I would have to say that in the long run things worked out fairly well for me. I was taken into a Quaker boarding school. People were kind. I went to college. I became a teacher. … I’ve been diagnosed as a depressive more than once.’

‘That Obscure Object of Desire’ starts with a quote from LuisBuñuel, in French. I needed to phone a friend; a translation would have been helpful. This distracted me from the account of Nelson, the software designer nerd with social problems who comes to an improbable end. The title story tells of the reunion of an odd father and his reluctant daughter, but suffers from an obvious dénouement and stilted dialogue. If the weather is supposed to be a pervading refrain, this is yet another whose isobars are too far apart. ‘Afterlife of a Stolen Child’ reads like a B-grade horror movie. Many of these tales suffer from sounding off-key as if, caught in some transnational vortex, Turner Hospital is no longer adept at either American or Australian idioms.

‘Moon River’, a memoir, concludes the book. Turner Hospital conflates the death of her mother in a hospital ward high above the turbulent Brisbane River with childhood memories of Brisbane’s tributary creeks, a brief account of the explorer John Oxley who named Breakfast Creek, and her mysterious great-grandfather’s voyage as a boy from England to Australia (only to be presumed drowned in the Brisbane River floods of 1893). The death of her mother is most affecting and shows what a fine writer Turner Hospital can be. She quotes Heraclitus: ‘Everything flows and nothing stays fixed.’ But Turner Hospital has not managed to sustain her voice with enough continuity and authority, and the narrative thread slips from her hand.

Comments powered by CComment