- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Cultural Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The international air hostess was the ultimate twentieth-century modern girl – mobile, cosmopolitan, glamorous. She was paid to travel around the world, journeys that, in the early years of intercontinental travel, could take several days and involve stopping at exotic places such as Singapore, Calcutta, Karachi, and Cairo on the ‘Kangaroo Route’ between Australia and London. She was, of course, a ‘girl’ (she had to resign from her job on marriage), she had to have a ‘good appearance and personality’, and her height and weight had to fall within narrowly defined limits. Her look had to match the glamorous mobility and cosmopolitanism that she signified. At the same time, her job was to look after people: she had to be easily identifiable as a staff member, and one belonging to a specific company. She had to wear a uniform – something anonymous that might seem to counteract the glamour of the job.

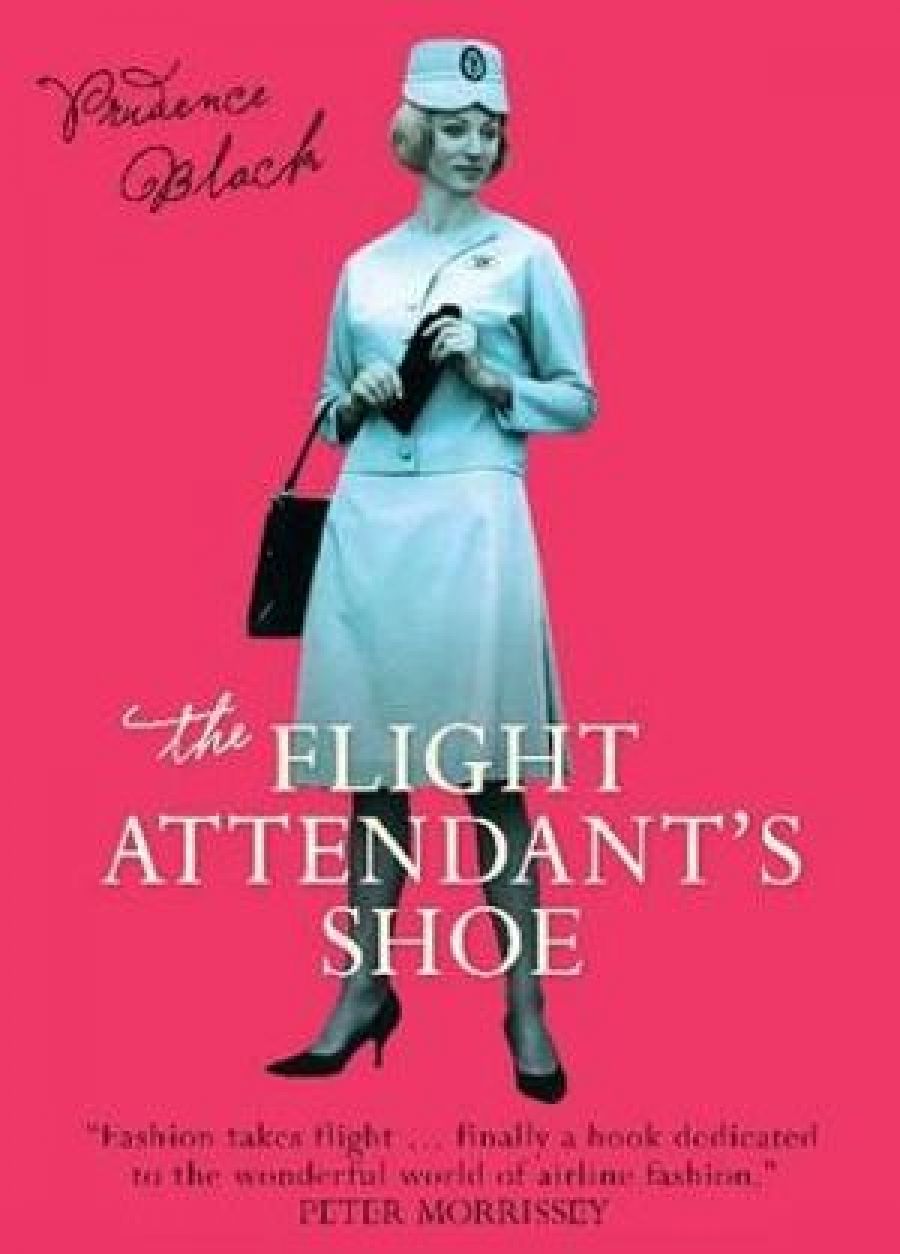

- Book 1 Title: The Flight Attendant’s Shoe

- Book 1 Biblio: New South, $49.95 pb, 368 pp

The subject of this book is the flight attendant’s uniform as it changed over time from the postwar years to the present day. Despite the fact that male flight attendants made up three quarters of the profession for a long time, their uniforms offer little grist to the fashion analyst’s mill, and in this book the emphasis inevitably falls on female uniforms and their wearers, for this is where the changes are most dramatic. The ‘flight attendant’s shoe’ of the title refers to the one item of the uniform that – while the clothes, the hat and gloves, the hairdos all change rapidly, with the pace of women’s fashion and changing styles of femininity – remains the same: the basic court shoe with the sensible heel, a reminder of the practicalities of the job.

The story begins with the military-style uniforms of the immediate postwar years, when Qantas (then Qantas Empire Airways) first employed hostesses, as local airlines had done since the 1930s. It was felt important to establish the professional nature of the job, and formality was the keynote. Those were the days when flying was a special occasion and passengers wore their best clothes. The ‘total demeanour’ required of hostesses involved voice training from an elocution teacher and beauty training from a representative of Elizabeth Arden. There were strict rules for how the uniform was to be worn. Uniforms were individually tailored, and included a starched white dress for stopovers in the tropics. A former hostess described nearly ‘passing out’ as she struggled to change into the appropriate uniform for landing in the tiny space of the airplane toilet. In such ways, hostesses’ bodies were trained ‘for the privilege of being corporate and nationalist showpieces’.

With changing airline technologies cutting travel times in half, by the early 1960s there were more international passengers travelling by air than by sea. Air-hostessing became a less exclusive profession, though there was often only one hostess on each flight, along with a number of stewards. Their uniforms of a dress and jacket were made of new synthetic non-creasing materials, and became fashion statements. The air hostess acquired an image in popular culture as an icon of stereotypical femininity, symbolised by the American bestseller of 1967, Coffee, Tea or Me?: The Uninhibited Memoirs of Two Airline Stewardesses.

At Qantas, however, strict discipline was maintained even when it followed other airlines by introducing a minidress as uniform – this one in hot orange, the colour du jour. It was not until the mid-1970s that hat and gloves were dropped from the uniform, but hostesses were still required to wear a girdle. This new uniform by Italian designer Pucci included a dress in a brightly coloured stylised flower print. Qantas’s most popular uniform ever, it lasted until 1987. The next major innovation was by Yves Saint Laurent, after an unsuccessful search for an Australian designer: it was practical and conservative, but for the first time included the option of trousers for hostesses. With the privatisation of Qantas and its eventually becoming the major national as well as international airline in the 1990s, uniforms designed by George Gross and Harry Who took on a generic corporate look, with no attempt to ‘represent what the flight attendant meant’. This trend has continued in the work of the most recent designer, Morrissey, whose major innovation was an Aboriginal-style print designed by the Balarinji Studio.

Essentially, as flying becomes less special and (often) more of an ordeal, the job becomes less glamorous and more corporate. The uniform has come to be more concerned with badging the company than with signifying the precise kind of femininity represented by the flight hostess. Prudence Black concludes that ‘a highly desirable profession’ has been ‘reduced to just another customer service role’. But I wonder whether this is such a bad thing, given that the ‘profession’ was so dependent on iconic femininity, a kind of geisha role in a gendered division of labour on board, where the hostess looked after the paperwork and entertained the passengers, while the male stewards served food and drink – and received higher wages, as well as tips. It was only in 1992, more than a decade after they took on equal roles with stewards, that Australian female flight attendants won equal pay and promotion opportunities.

The Flight Attendant’s Shoe is beautifully produced, each of its ten chapters lavishly illustrated with colour plates and even colour transparencies showing the fabric and cut of various uniforms. Although the book is not specifically about Qantas, its wonderful illustrations, and most of its history, come from the Qantas archives, as the author, Prudence Black, acknowledges. As a result, it indirectly offers something of a corporate history of the company, which is also a story of ‘the crafting of a nationalist-cosmopolitan culture’, as Qantas became a ‘major investor’ in Australia’s postwar growth and, when it was privatised, undertook to remain identifiably Australian.

Above all, the book offers the fascinating story of a female profession as defined by its uniforms, meticulously documented and contextualised in relation to airline history as well as fashion history. While its arguments about modernity are persuasive, I would have welcomed more analysis of links between modernity and gender, and a closer look at the relationship of femininities and masculinities in this profession. New South, an imprint of the University of New South Wales Press, has excelled itself in its production values, but in some ways the coffee-table book features of The Flight Attendant’s Shoe overshadow its cultural analysis.

Comments powered by CComment