- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: International Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Many of us would find it as hard as Shaw’s Ladvenu does to think of any good reason for torture. It seems medieval, it is abhorrent, it is internationally illegal, and it doesn’t work. Statements made under torture are legally useless, and their value as intelligence is not much better ...

- Book 1 Title: The Politics of Prisoner Abuse: The United States and Enemy Prisoners after 9/11

- Book 1 Biblio: Cambridge University Press, $34.95 pb, 331 pp, 9780521181105

The perennial American answers include: these are bad guys, so they deserve it; others do it, so we merely copy their techniques; terrorists attacked us, so we have to retaliate in kind; foreigners hate our freedoms and the rule of law, and we won’t allow them to dictate our justice system; torture is the lesser of two evils; anyway, what we do isn’t torture. That leads to another question: if torture is right, why deny it?

After the Bush administration gave up denying it, Americans such as Glenn Carle and Michael Otterman wrote critiques of US torture, as has Gareth Pierce in Britain. But Bush’s British and Australian allies denied being complicit in his ‘authorised and monitored abuse’, which we later discovered they were. There has been no outcry. Why not?

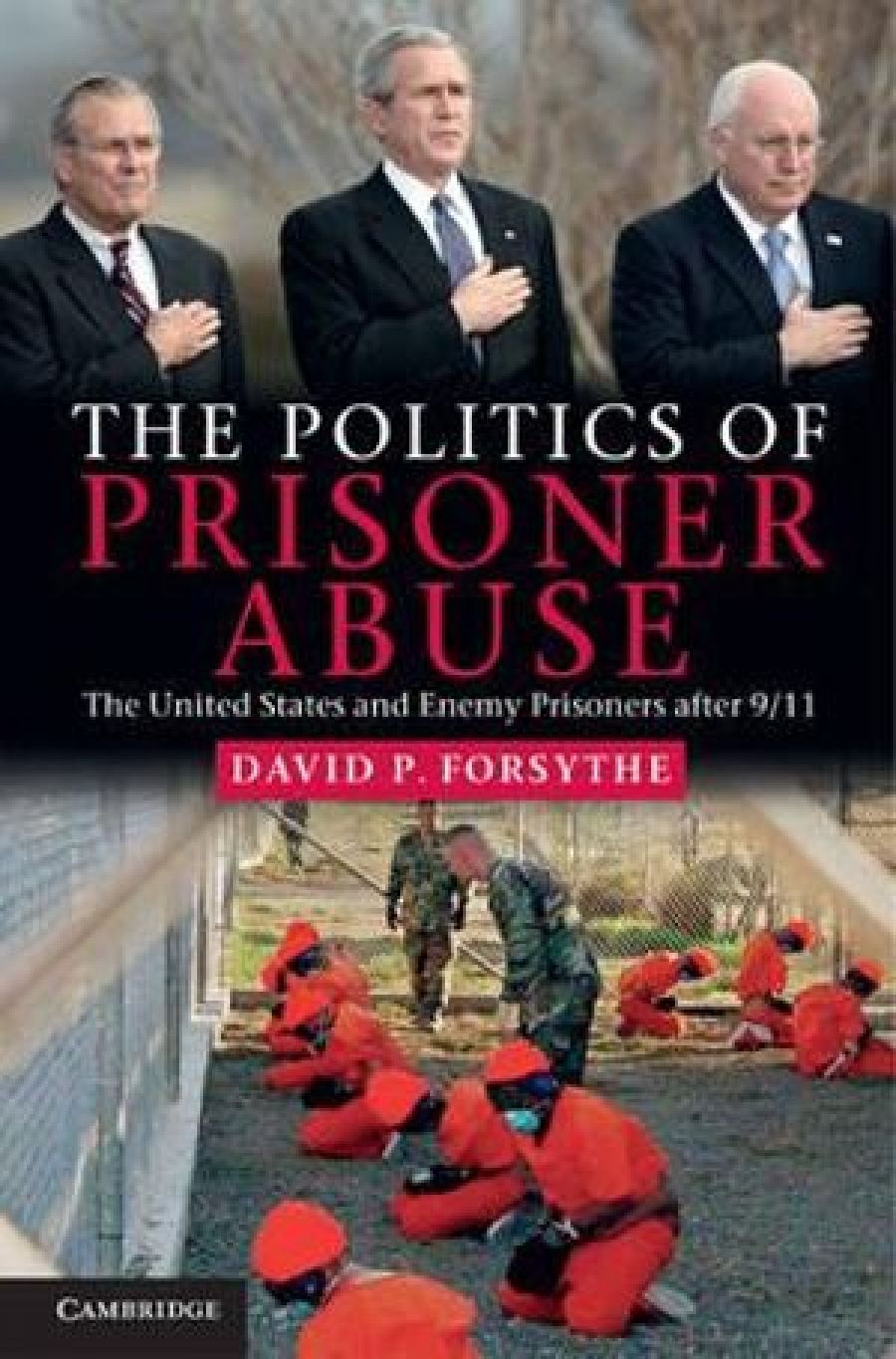

David P. Forsythe’s book offers some answers. On the cover is the Bush/Cheney/Rumsfeld troika, hands on hearts, flag badges in lapels, in identical dark suits and white shirts, lined up for some patriotic occasion. At the bottom are nine prisoners, wrists tie-taped, in identical orange tracksuits and caps, kneeling in line, facing wire walls, while two guards in US military uniforms stand over them. At the top you see vengeful pride and power, at the bottom, humiliation. At the top are the former governor of Texas who approved 152 executions (more than any of his modern predecessors); the former head of the profiteering Halliburton who, as vice president and afterwards, displayed what Forsythe calls ‘rigid and unending endorsement of major abuse’; and the former secretary of defence who, because he liked to read and write standing at a lectern, denied that ‘stress positions’ were torture. As always, the powerful do as they wish because they can, and the powerless put up with it because they must: has anything changed since ancient Greece?

Well, yes, if it’s true that the Guantánamo prisoners committed a new sort of crime, not ‘merely’ hijacking, conspiracy, or murder that could be dealt with after the event, under existing criminal law in regular courts. In the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia after 9/11, new laws (many more in Australia than elsewhere) were written to prevent anticipated crimes. Arrests could be made on mere suspicion, communications could be invigilated without warrant, suspects could be held incommunicado for long periods, and freedom of speech and reporting could be curtailed, as they still can, ten years on. Guantánamo remains open. In Britain, the government is winding back some of these offences, in keeping with its human rights obligations, but in Australia anti-terror laws are still in force. Michael Ignatieff has asserted that in any state that has the power to detain at pleasure and in secret, abuse of detainees is inevitable. Could this happen in Australia too?

American leaders and their lawyers were clearly determined to deal as harshly with ‘enemy combatants’ (Forsythe prefers ‘enemy prisoners’) as they could. They distorted US and international law, including treaties and conventions that the United States had helped to create, found the Geneva Conventions ‘quaint’, and applied them selectively in different countries. The Bush administration repeatedly advised Iraqis not to abuse prisoners, even while Khalid Sheik Mohammed was ‘waterboarded’ in US custody 183 times in one month. Forsythe estimates that in ten per cent of seizure and abuse cases, the CIA had the wrong person, while the rate for the military was sixty to eighty per cent. Bush admits in his 2010 memoir that he authorised ‘abusive interrogation’ by the CIA. For that, and for what the military did, he may be prosecuted if he ventures abroad, as may Cheney and Rumsfeld. Fortunately, or intentionally, he rarely travels.

Whether all the denizens of ‘Gitmo’ were indeed the ‘worst of the worst’, as Bush and his allies claimed, or some were merely small fish scooped up in the trawl for terrorists, the world’s sympathy for Americans after 9/11 turned to disgust at the images from the camp in Cuba, then more from Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, and then the video released by Wikileaks of the Apache helicopter massacre. When a nation that claims to set world standards fails to live up to them, it damages not only itself but also the standards. Human rights, transparency, and good governance are preached to developing countries: why, they might ask, do the preaching countries not exhibit them? Public accountability and equality before the law are claimed to be sacrosanct: why are they selectively applied? Why are leaders of minor countries arrested for war crimes and not those of major ones?

On all these questions, Forsythe is forensically fair, although, as an international human rights academic, his pain about continuing US policies is palpable. Voters believed Barack Obama would close down Guantánamo and the military commissions, but he did not. He apparently shut down the CIA’s ‘black sites’ and forbade ‘most’ inhumane treatment and torture; and it is true that under Obama the 2009 Detroit terrorism case, transparently processed as a criminal matter, produced cooperation and a confession from the Nigerian perpetrator. But renditions apparently continue, and no Bush people face criminal prosecutions. Forsythe speculates that, like Cheney, Obama fears another terrorist attack that he has not done everything he can to forestall. But the United States and the United Kingdom, which claim they support humanitarian law and oppose torture, cannot rationally justify undermining their own principles. Nor can Australia.

Comments powered by CComment