- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1848 Ludwig Leichhardt and half a dozen companions set out from Queensland’s Darling Downs, intending to cross the continent to the Swan River Colony in Western Australia. The entire expedition disappeared, virtually without trace. Since then at least fifteen government and private expeditions have tried to ...

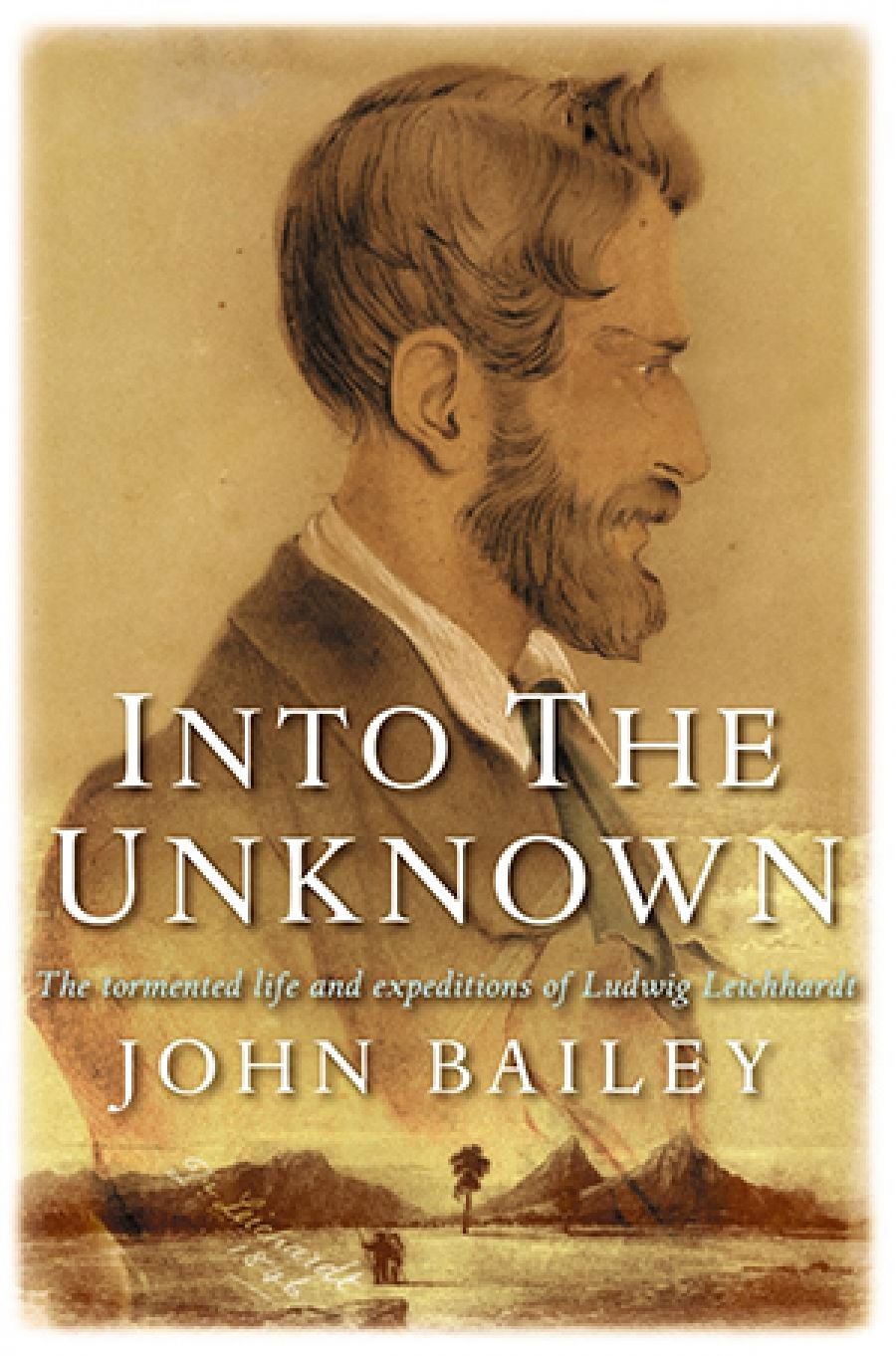

- Book 1 Title: Into the Unknown: The Tormented Life and Expeditions of Ludwig Leichhardt

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, $34.99 pb, 381 pp, 9781742610450

Explanations as to why the 1848 expedition disappeared have largely focused on Leichhardt’s practical and leadership skills, and, especially, on his personality. These are elusive qualities to determine at the best of times, but particularly difficult after 160 years and when many descriptions of the man clearly were influenced by personal grudges or prejudices. What can be said with certainty is that Leichhardt was highly intelligent, well educated, personable in ‘civilised’ society, passionate, enthusiastic, determined, and dedicated. Beyond this it is difficult to separate reality from prejudice, or what he represented rather than who he was. The poet Francis Webb was undoubtedly correct when he suggested that Leichhardt has been viewed by each generation according to the requirements of the times.

Generally speaking, Leichhardt has had a bad press. Within a few decades of his disappearance, he was severely criticised by several members of his first two expeditions, who described him variously as moody, taciturn, selfish, a glutton, and more, but not all of the members were upset with him. After the collapse of his second expedition, several of its members seemed happy to accompany Leichhardt on a reconnaissance from the Darling Downs to ‘Mitchell’s track’ on the Maranoa River; and at least two were prepared to start out again on Leichhardt’s final attempt to reach Swan River – good evidence that he was not as bad as the other expedition members made out. This was either unknown to, or conveniently ignored by, later critics.

With the rise of nationalism in the 1880s, the Bushman became the epitome of the ‘real Australian’. Ignoring the fact that Leichhardt was highly constrained by a lack of funds, and by the technology and general level of bushmanship of the times, and no doubt swayed by the published and highly negative accounts of two of the disgruntled members of Leichhardt’s first two expeditions, it was easy to criticise his supposed shortcomings as a bushman and a leader.

The Great War saw vitriol and discrimination directed at Germans generally. In this atmosphere, Robert Logan Jack (1921) published another highly prejudiced assessment of Leichhardt’s worthiness as an explorer. The first book-length biography of Leichhardt appeared in 1938, a reasonably balanced account written by Catherine Cotton, but it was soon overshadowed by the renewed conflict with Germany and the publication of Alec Chisholm’s extraordinarily prejudiced and inaccurate biography, Strange New World (1941).

The final blow against Leichhardt’s reputation came with publication of Patrick White’s novel Voss (1957). Although not intended to be a biography of Leichhardt, the ‘megalomaniac German’ in the novel was in large measure based on the negative image of Leichhardt built up by previous writers. Since its publication the fictional character of Voss has merged with the historical Leichhardt, as defined by Chisholm and others, in a process that Horst Priessnitz (1991) has termed ‘the “vossification” of Leichhardt’. Over the past thirty years, the tide has been turning against this enduring image. First came Elsie Webster’s book, Whirlwind in the Plains: Ludwig Leichhardt – Friends, Foes and History (1980), which laid to rest most of the criticisms levelled against him by his former expedition members. In 1988 Colin Roderick accelerated the process when he published a carefully researched and decidedly sympathetic biography, Leichhardt: the Dauntless Explorer (1988). Since then, several other writers have discussed various aspects of Leichhardt’s professional capabilities, and come to highly favourable conclusions. Among historians and scientists, Leichhardt is now generally recognised as the best-trained scientist in Australia in his time, an accurate and insightful observer of the world, a good navigator, a man willing to learn from experience, and probably the explorer best able to live off the land – in short, a competent explorer and, at least, a reasonably good bushman.

John Bailey’s Into the Unknown: The Tormented Life and Expeditions of Ludwig Leichhardt is the latest contribution to the ‘debate’ about Leichhardt. It is his sixth book and fourth historical work. All were written with the aim of making the ‘average reader’ interested in what he himself finds interesting, and he has succeeded among general readers and critics alike. His works have all received warm reviews, and his book The White Divers of Broome: The True Story of a Fatal Experiment (2001) won the New South Wales Premier’s Community and Regional History Prize. Into the Unknown is likely to receive similar accolades.

So what line does Bailey take in Into the Unknown? The answer certainly is more for Leichhardt than against. His avowed intention is to ‘Let Leichhardt speak for himself!’ and to make ‘a further contribution to the restoration of Leichhardt’s reputation and an acknowledgment of his great achievements in science’. This he achieves by including a plethora of direct quotes from Leichhardt’s journals, diaries, and letters, and from those of his fellow expedition members and others. This allows the reader to consider both sides of a given situation and to form his or her own opinion. It is a timely book, the first biography of Leichhardt for thirty years, and the first that is highly readable and accessible to the general reader.

That said, scholars or others well versed in the Leichhardt story will find little that is new, and may well notice a number of minor, though irritating, mistakes. For example, Bailey describes how Leichhardt’s Aboriginal assistant, Charley, would climb trees to cut out honey, ‘Not the slightest bit concerned at being stung’. Nor should he have been concerned: Australian native bees are stingless. Elsewhere, he describes Edwin Lowe as an anthropologist. But Lowe was a pastoralist, the owner of Mount Dare station in northern South Australia. Again, Bailey tells us that human bones found at the edge of the Simpson Desert by Sub-Inspector James Gilmore were sent to Melbourne where they were declared to be European. This is true, but they were first examined in Brisbane by several members of the Queensland Medical Society and found to belong to an adult and a child, both Aborigines. Referring to a brass plate stamped ‘Ludwig Leichhardt 1848’, Bailey says it was bought by the National Museum of Australia in 2006 and authenticated in 2007. Quite the reverse is true, with detailed scientific examination being carried out to authenticate the relic before purchase by the museum.

In spite of these relatively minor irritations, Into the Unknown is a generally reliable, readable, and sympathetic biography of an otherwise much-maligned explorer. It undoubtedly will be well received by the general public, at which it is clearly aimed.

Comments powered by CComment