- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

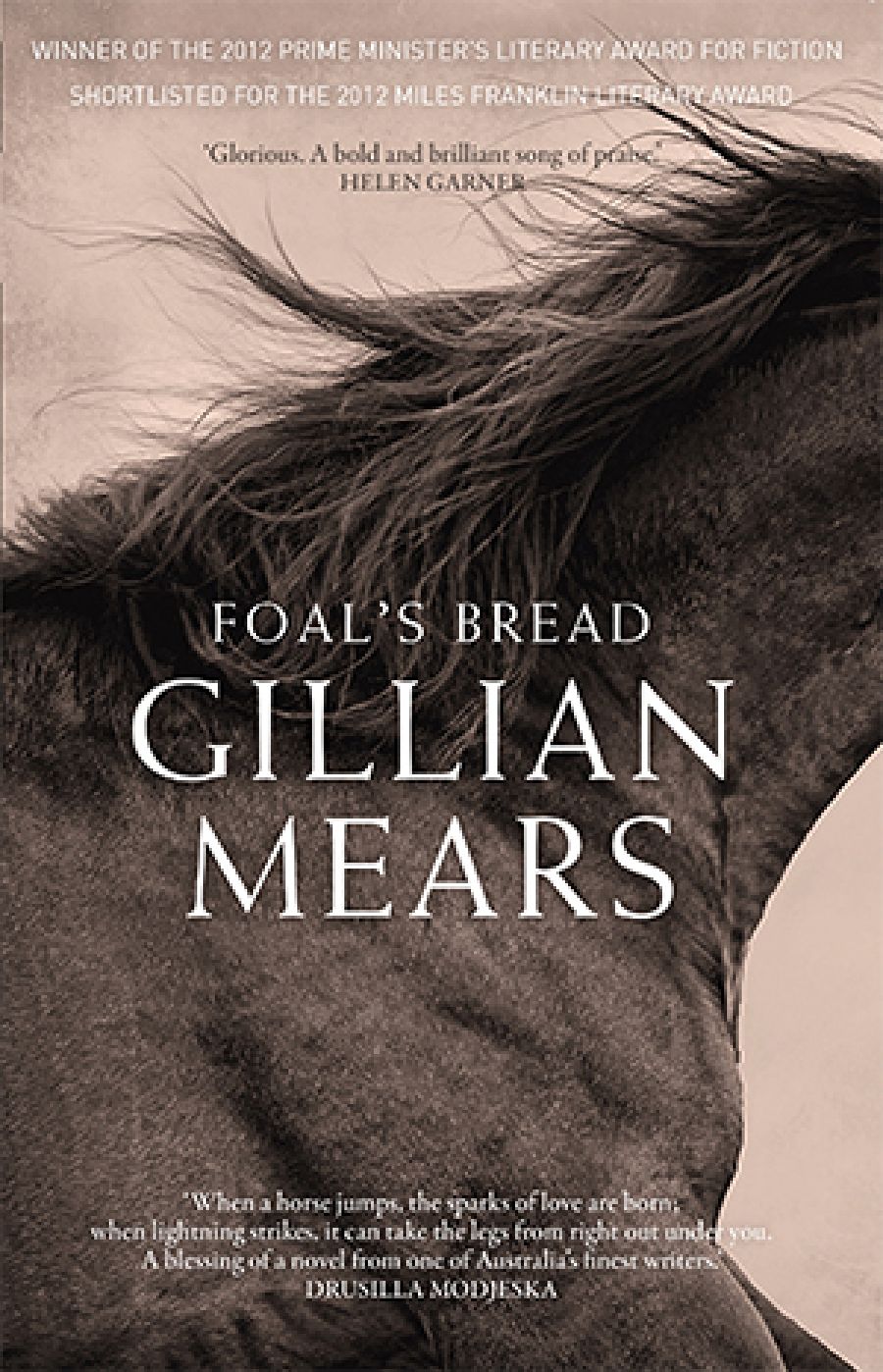

Gillian Mears has been to death’s door and back. Her wonderful essay ‘Alive in Ant and Bee’ (2007) recounts the journey and the exquisite pleasures of her life as a survivor. Writing has taken a back seat, understandably, over the past decade or so. There has been a short story collection, A Map of the Gardens (2002), but a novel from Mears is quite an event, sixteen years after her last, The Grass Sister (1995), won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize. It has been worth the wait. Foal’s Bread is a big and generous novel, set on a dairy farm in northern New South Wales in the mid-twentieth century: hard and often bitter times. In Mears’s world there is magic in the everyday, and portents everywhere.

- Book 1 Title: Foal’s Bread

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.99 pb, 360 pp, 9781742376295

Despite its breadth of vision, the novel’s cast of main characters is small enough: Roley Nancarrow and his wife, Noah (‘What kind of name is it? Couldn’t they spell?’ her mother-in-law grouses); his parents and sisters, and their children, Lainey and George, beloved but not ‘the full quid’; and the horses, which are as important as the humans. Roley first sees Noah in 1926 when he is a champion show-jumper and she a fourteen-year-old hopeful, travelling with her father. He doesn’t know, and never knows, the secret that colours her entire life: a child begot by her elderly uncle, recently dead, born by a river and sent downstream in a butter box.

Mears keeps the rhythm of the narrative even and plangent, giving forewarnings with what feels like kindness, rather than confronting us unawares with the stark and terrible events of her story:

The thin crescent moon was like a happy mouth, made of silver. Then two twinkling stars, in exactly the right place for eyes. From out of her pocket Lainey drew the corner piece of Auntie Ralda’s Blanket Icing she’d been saving. Her father was smoking and Lainey, looking from him to the moon to the little red tip of his smoke, thought she’d never been so happy.

No one saw the moon except for Lainey, and unable to know that she would never see it in that position again, she let the truck rock her to sleep at last, the icing falling into her lap.

Although she writes in the third person, which allows such hints of omniscience, Mears usually keeps her point of view closely aligned with her characters. Noah knows her baby must remain a secret, but she loved her Uncle Nipper and it is not until well into the book that the narrator offers any overt criticism of him. Roley, struck by lightning, has become gradually impotent, and Noah is frustrated: ‘Incapable of comprehending that having been awoken so young she could never be peaceful again, she tried to ignore the inappropriate longings rising under her town dress.’ History looks like repeating itself, though, with her daughter Lainey and a ‘particularly decrepit’ great-uncle. ‘The love young girls have for old horsemen is sweet and thick,’ the narrator claims. ‘It’s the stories that old man can tell.’ I suppose teenage girls have changed since the 1940s. Throughout the book it is constantly but silently asserted how much has changed. Once or twice the nostalgia becomes explicit: ‘the great era of the show-ring high jump was just about over’, for example. A coda brings the elderly Lainey back to her childhood home to witness the inevitable development and decadence of a place where she is no longer known.

Mears’s narrative voice slips in and out of the vernacular in a controlled and sustained exercise of free indirect discourse, with the imagery always grounded in the characters’ sensory memories. Noah, fourteen years old, giving birth, finds it ‘worse than being kicked in her knee by that bitch of a pony with the seedy toe Uncle Nip had needed a hand with. Worse than being food poisoned last New Year off her aunties’ mouldy Christmas meat.’ Later Roley, desperate to recover the use of the lower half of his body, prays, putting it ‘reasonable like to God. That with his father gone and him the only male on the farm now, bar one work dog, two mousers and George, well, I’m gunna need me legs, God.’ Oddly, when the non-vernacular passages in the narrative are taken out of context they can seem somewhat sententious, but as part of a whole they are enchanting.

The pathos of Roley’s decline and Noah’s maddening despair is compounded by everything that isn’t said, that can’t be said: the great Australian inarticulateness, partly self-deception, partly bravado. On their first meeting, Roley overhears Noah crying at being eliminated from the competition, but she explains it as ‘just an old bit of gripey gut. Been giving me jip.’ Twenty years later, she tries to save face by explaining her shaming hangover as ‘the vomitin’ brucellosis’ caught off the calves. Roley, bedridden, suspects Noah of infidelity, but he can’t ask her for reassurance, and she can’t express her love, though ‘she felt an immense tenderness threatening to put her to her knees’.

Foal’s Bread is a grand, bittersweet romantic saga, at once laconic and mystical, tragic and optimistic. It is filled with an understanding of horses and country life not just researched but also deeply internalised, like the Australian vernacular that Mears so effortlessly reproduces. How marvellous to hear her unique voice again.

Comments powered by CComment