- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letters

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

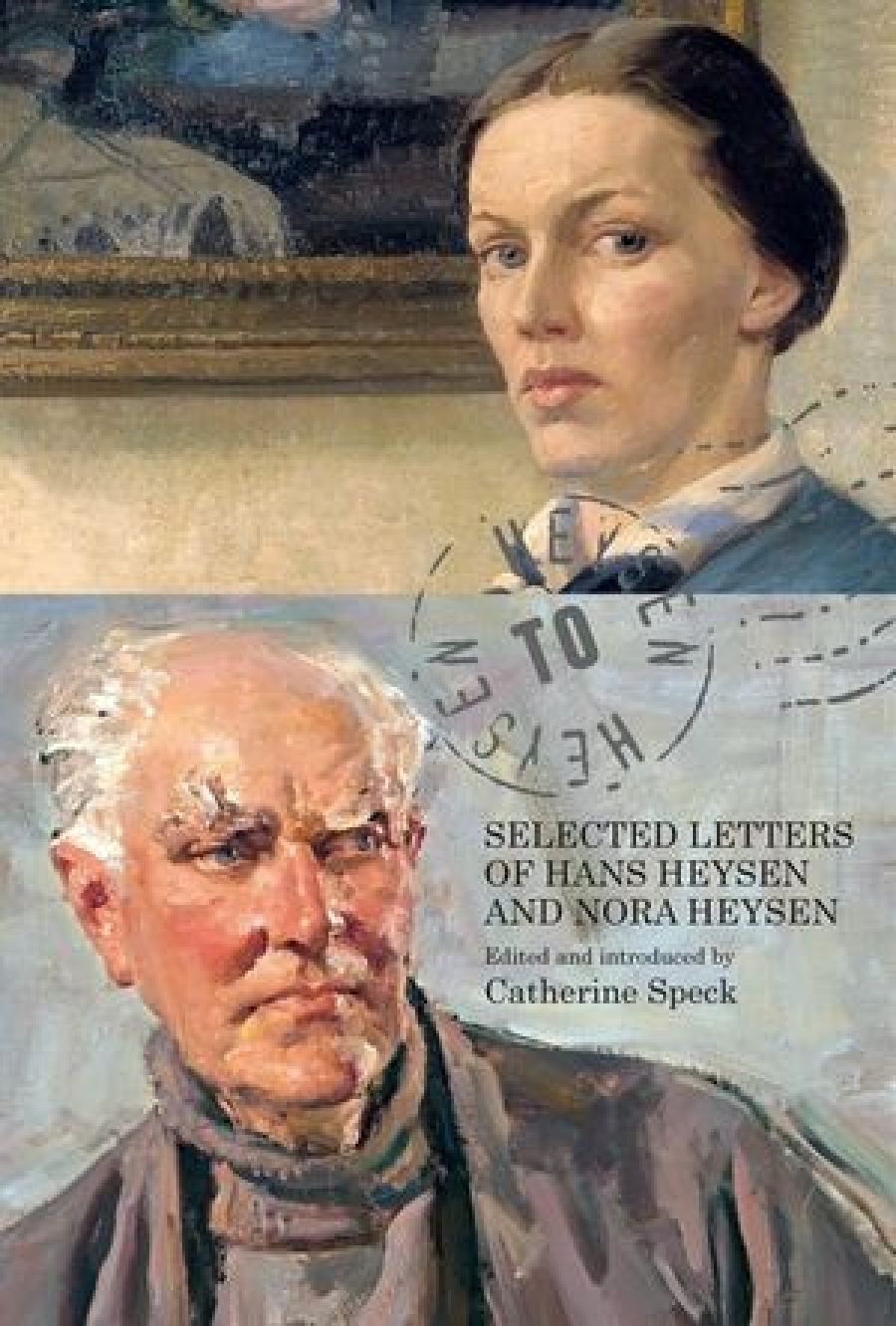

A thirty-year correspondence between two Australian artists is notable, but when the artists are father and daughter it is doubly interesting. Hans Heysen and Nora Heysen corresponded regularly throughout their lives: Hans writing from The Cedars, the family house near Hahndorf, in the Adelaide Hills; and Nora from Sydney, London, New Guinea, Pacific Islands, or wherever she happened to be. Hans Heysen is celebrated for his landscape paintings – those South Australian views of eucalypts in a landscape, which changed the way generations looked at the Australian countryside – and for his desert landscapes of the Flinders Ranges. Nora, the only one of his nine children to become an artist, is known for her still lifes and portraits. Their work is well represented in Australian public collections. Hans was unquestionably the better artist, and always had the greater reputation. Nora, however, won major prizes (including, somewhat controversially, the 1938 Archibald Prize) and managed to forge an independent career for herself; she by no means lived in her father’s shadow.

- Book 1 Title: Heysen to Heysen

- Book 1 Subtitle: Selected Letters of Hans Heysen and Nora Heysen

- Book 1 Biblio: National Library of Australia, $49.95 pb, 358 pp

Catherine Speck’s edited correspondence, Heysen to Heysen, gives a fascinating view of the relationship between the two artists and of the art scene in Australia and abroad from the 1930s until 1968, when Hans died at the age of ninety. The letters combine familial and artistic subjects. Apart from art, Nora liked music and opera. She regularly mentions food and drink, and rhapsodises about a Mettwurst in 1940: ‘The sausages have arrived in first-rate condition and a great thrill it was to receive them.’ These are personal letters, not necessarily written for an audience wider than their immediate family circle, and presumably not created for posterity. This extensive and valuable correspondence has survived and is now held in the National Library of Australia, which has published this volume. Both writers were aware of and read published correspondence between artists, and they refer to Camille Pissarro’s letters to his son Lucien. Perhaps they thought this might be the fate of their own correspondence.

While both artists are chiefly remembered in old age – Sir Hans Heysen rather formal as the grand old man of his generation; Nora ever forthright and not far from a cigarette – the letters give both characters a revealing youthfulness. The language of the correspondence is refreshingly modern; father and daughter are remarkably candid. Of course, it is their views about artistic contemporaries and their work that is most compelling. Here, Nora is more forthcoming; because of her travels she saw much more contemporary art. In 1937 she wrote from London: ‘Picasso is holding an exhibition at the moment. I went to see it and came away with the feeling that he was a charlatan.’ She did not ‘get’ Ian Fairweather, but appreciated something in his work: ‘you can’t dismiss it as rubbish, for it is extremely well organised and executed.’ John Olsen she considered ‘an engaging doodler’. Of Sidney Nolan’s 1950 Sydney exhibition she wrote: ‘There was something phony about it, too slick … He paints with duco and his skies are sprayed on.’

Although there are many more letters from Nora than from her father, Hans’s letters also make particularly interesting reading. He discusses acquisitions made by the Art Gallery of South Australia, of which he was for many years a trustee, and gives Nora advice and criticism about her work and personal matters. Both of them discuss the art market and sales of their new works and those of other artists. There is much interesting gossip about the Australian art scene, particularly in Sydney, where Nora settled. Jeffrey Smart is mentioned often, as are the rich Adelaide collectors Ursula and Bill Hayward. We learn about the process of portrait commissions and about the behaviour of the Sydney social set.

Despite the negative criticism that Nora received when training to be an artist, she never doubted that art was her rightful vocation. Many aspiring artists might have given up when criticised in the following way in their early twenties:

I got a criticism for my drawing from Bernard Meninsky. He was scathing and gave me the worst most damning criticism I’ve ever had. In fact he had not one good word to say – my drawing was lifeless, dull, formless and superficial and the technique was like sandpaper.

Nora was not one to wilt because of adverse criticism or difficult working conditions. Even when she had established herself as a professional artist, she rarely had it easy. She seems to have had many encounters with rats. As an official war artist in New Guinea, she dispelled any sense of glamour or entitlement in her letters home: ‘Worse than all this are the rats. They are here in millions, every night one gets into my bed … If there is one thing I hate it is rats in my bed.’

The letters are grouped in chronological sections. Catherine Speck offers just the right amount of background; she introduces each chapter and provides informative notes on the considerable cast mentioned in the correspondence. Those with an interest in the Heysens or in twentieth-century Australian art will find this a satisfying read.

CONTENTS: NOVEMBER 2011

Comments powered by CComment