- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Photography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

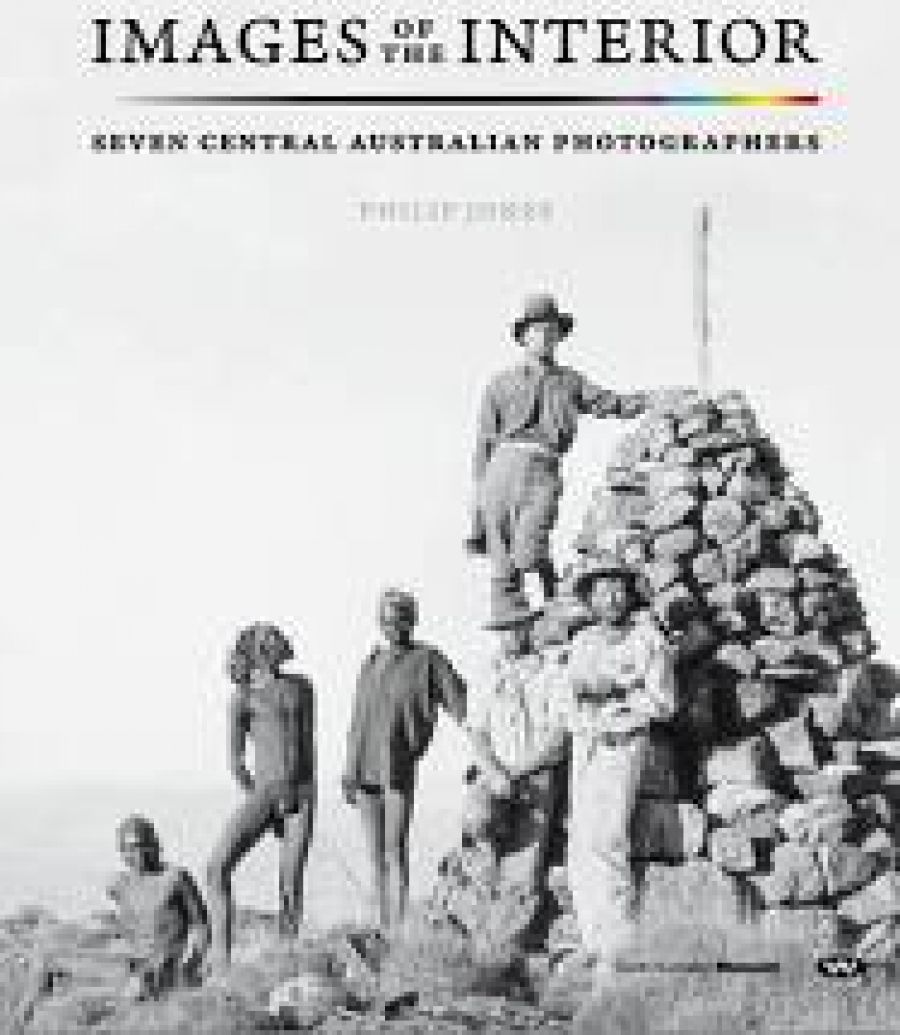

One section on Australian photography slowly growing on my bookshelves is devoted to anthropological and ethnographic photography. Philip Jones’s latest book, Images of the Interior: Seven Central Australian Photographers, belongs there because of the amount of anthropological material it contains. But it could also take its place among books devoted to vernacular photography, because none of the seven photographers Jones has selected was professionally trained. All were keen amateur photographers who produced substantial bodies of work during the time they lived and worked in Central Australia. The book deals with an epoch of dramatic change, beginning in the 1890s with some of the earliest European photographs of the Centre, and concluding in the 1940s.

- Book 1 Title: Images of the Interior

- Book 1 Subtitle: Seven Central Australian Photographers

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield Press, $39.95 pb, 161 pp

The eighty-four photographs are from the South Australian Museum, part of collections that Jones assiduously developed during the 1980s and 1990s. Prints from the negatives had their first outing when they were exhibited at the Museum in 1998, and they were recently shown there again in an expanded exhibition that will now tour to Australian and international venues. Images of the Interior accompanies the exhibition but has been conceived as a book, rather than as an exhibition catalogue.

Through his curatorial projects and publications, Jones has long been committed to bringing his research into the Museum’s collections to the view of a broad public. His writing in Images of the Interior is typical of his practice, addressing the specialist and general reader alike. The essays, which introduce each photographer’s portfolio of images, are biographically based, easy to read, and filled with new information.

The seven photographers in the book are Francis J. Gillen, Samuel White, William Walker, George Aiston, Cecil Hackett, Ernest Kramer, and Rex Battarbee, some of whom are far better known than others. What is most striking about the group overall is the diversity of the men’s backgrounds – ranging from telegraph stationmaster, ethnographer, ornithologist, and conservationist, to police trooper, storekeeper, evangelist, and physical anthropologist. But these individuals also had much in common; most notably, they all interacted with and documented the lives of Aboriginal people on the Central Australian frontier, producing images that are striking in their immediacy and relative lack of formality.

The nature of each photographer’s engagement did of course differ, due to their varied backgrounds, interests, and concerns. However, Jones underlines their shared sympathetic responses to the situation that Aborigines were confronting in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He argues, for example, that Aiston, a Sub-Protector of Aborigines ‘responsible for distributing rations to the sick and needy’, understood they were caught between a hunting and gathering existence and settler culture. The photographs show this ‘dilemma’ in action. Aboriginal people are photographed engaging in traditional activities and ceremony, and at work for their European bosses (Jones notes this was often not for wages, but for rations).

Of the photographers represented in the book, three are standouts: Francis Gillen, Ernest Kramer, and Cecil Hackett. Gillen’s work is not a surprise. His photographs, especially his portraits of Aboriginal people and his beautifully observed studies of their daily activities, are already appreciated for their naturalness. This arises from what Jones describes as ‘a relationship based on mutual trust’. But what of Kramer? He was an evangelist and reformer who criss-crossed Central Australia with his caravan mission, eventually establishing a home at Alice Springs with his wife and family. His photographs are also strong, with the image of a Luritja man, Nanatugurba, and a young boy, Nanabanji, holding a snake, being especially memorable (see opposite). Its narrative richness is strengthened by a small detail. The bandage that protected the boy’s sore knee has slipped down and circles his ankle, providing a white accent in the composition. The photographs by Hackett, a medical scientist, are noteworthy because of their personal, respectful qualities. Hackett accompanied ethnologist Norman Tindale on an expedition in 1933 when they travelled with the Pitjantjatjara people through the Mann Ranges (Hackett’s role was to make body measurements and determine blood groups). He wrote that the experience of being with the Pitjantjatjara ‘made a lasting and humbling impression … Their detailed knowledge of their country, their many skills and their intelligence soon gained our respect.’

The interest of Images of the Interior isn’t confined to the photographs. The stories of the men and women involved in securing them are compelling too. William Walker, a doctor, and his wife covered ten thousand kilometres in a Model T Ford, which is the subject of an image taken in 1927. It reveals some ingenious packing as equipment and supplies are strapped neatly to every available surface of the car.

The last photographer in the book is Rex Battarbee, the artist associated with the Arrernte School of watercolourists, and Albert Namatjira in particular. Battarbee’s are the only examples of colour photography, signalling what Jones argues was an historic shift away from the dominant image of the interior as a black-and-white landscape to one that is ‘colour-drenched’. The latter is of course the Central Australia beloved of the modern tourist industry. Images of the Interior closes with Battarbee’s photograph of the door in his house, specially constructed with a small porthole window. Through it he could see a stunning Central Australian scene taking in the Todd River and Alheke Ulyele (Mt Gillen).

The men whose photographs are featured in Jones’s book went into the interior for reasons related to their vocations. Fortunately, they took their cameras with them. Their firsthand accounts give some inkling of the complexities and consequences of European incursions into Central Australia.

Comments powered by CComment