- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Britain in the later nineteenth century witnessed a radical rethinking of the role of art and design in society, one in which the earlier generation’s enthusiasm for industrial innovation and material betterment was replaced by a growing recognition of the necessity of beauty – in art, in literature, in furnishings, and in fashion – as the foundation stone of modern living. Emerging from bohemian artistic circles and avant-garde design, a new concept of beauty developed that was expressed in a variety of forms. These ranged from pictures whose meaning no longer resided in their narrative or moral content, but in the decorative balance of colour and line (summed up by the phrase ‘Art for Art’s sake’ and epitomised by the exquisite paintings of Albert Moore and James McNeill Whistler); to books of verse by William Morris or Algernon Swinburne, in which the elegance of the metrical form was matched by the stylishness of the type and cover design; to the ideal of the ‘House Beautiful’, where the subtlety and harmony of one’s arrangement of wallpaper, furniture, and objets d’art were now recognised as valid expressions of refinement and individuality.

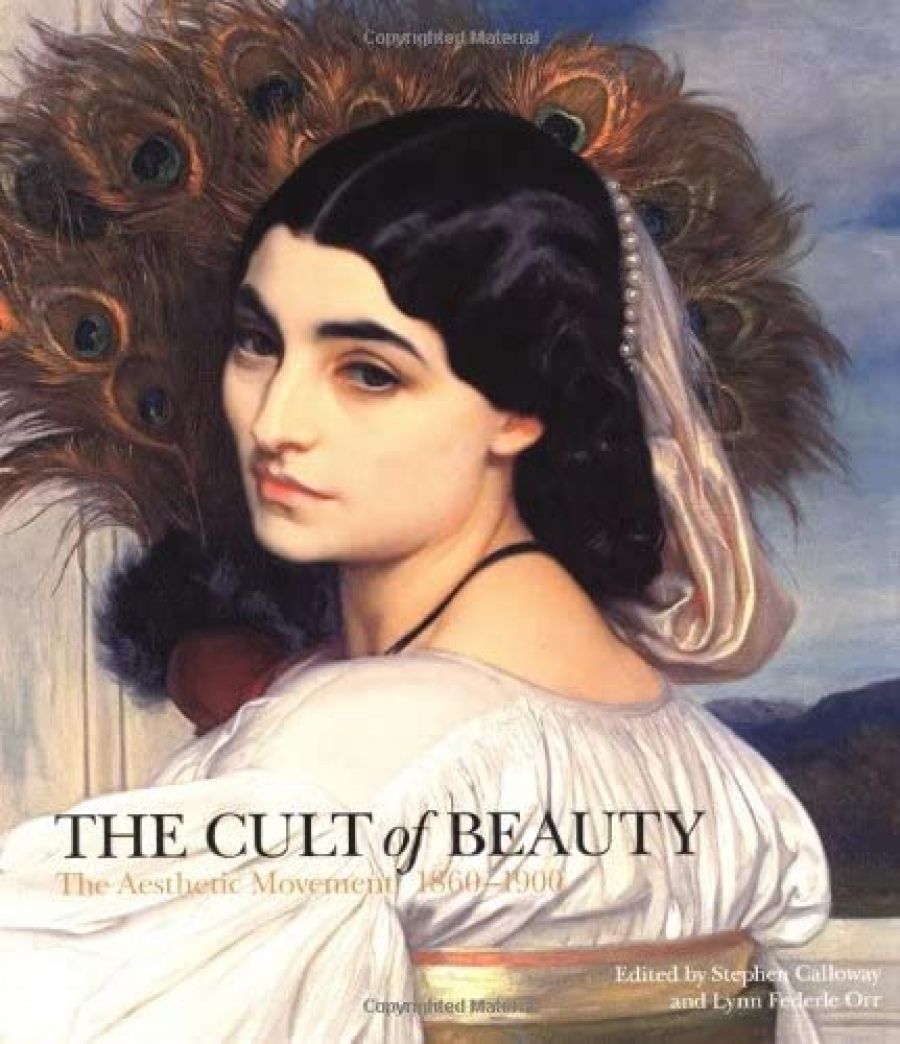

- Book 1 Title: The Cult of Beauty

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Aesthetic Movement 1860–1900

- Book 1 Biblio: V&A Publishing, £40 hb, 288 pp

Moreover, the visual language of Aestheticism, as this movement came to be known, drew upon a distinctive repertoire of tertiary colours, exotic motifs, and decorating devices – such as shades of green, yellow, and peacock blue; sunflowers and lilies; the display of Japanese fans on walls, and blue and white china on dressers; dados, stencilled friezes; lacquered cabinets and rush-bottomed chairs – all of which were easily promoted by the burgeoning artistic retailers and authors of advice books, and eagerly emulated by the aspirational middle classes. As Deborah Cohen has observed of this period: ‘An artistically furnished room did not simply express one’s status; it conferred status. The question of the day … was not “Who are they?” but “What have they?” … What you owned told others (and yourself) who you were.’

The rise of this new religion of beauty, its dissemination into the marketplace, and its unprecedented popularisation throughout late Victorian Britain is the subject of a wide-ranging and lavishly illustrated book entitled The Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement 1860–1900, published by the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in conjunction with the large exhibition that will tour from London to Paris to San Francisco during the next twelve months. This show represents the latest in a series dedicated to the great decorative arts movements, and the accompanying book adopts an established format of chapters and shorter essays by specialist authors, many of whom are curators at the V&A. Certainly, this institution is the natural home for such a project; in its earlier incarnation as the South Kensington Museum, it was responsible for commissioning two of the great proto-Aesthetic interiors (Morris’s Green Dining Room and Poynter’s blue-and-white tiled Grill Room), and it went on to collect all the myriad aspects of the fully fledged movement, from stained glass and textiles to jewellery, posters, and photography. Furthermore, it was V&A scholars such as Elizabeth Aslin who, in the mid-twentieth century, helped pioneer the ‘rediscovery’ of the Aesthetic Movement and establish its place in the history of design. Fittingly then, the Museum’s vast multidisciplinary collections supply the majority of items on display and discussed in the book; although it should also be noted that the exhibition borrowed from more than seventy private and institutional lenders, resulting in, to quote the book’s editors, ‘an unrivalled array of both the fine and decorative arts of the period’, numbering almost three hundred objects, including over sixty paintings.

Indeed, it is the presence of the fine arts – in the form of grand paintings, formal and ‘fancy’ portraits, and examples of the ‘New Sculpture’ – prominently positioned alongside the decorative arts that distinguishes The Cult of Beauty (both book and exhibition) from preceding studies of the Aesthetic Movement, in which the design, applied arts, and popular aspects have taken precedence. In this respect, The Cult of Beauty is simply reflecting much of the recent scholarship on Victorian art that focuses on figures such as Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Watts, and Leighton, and their role in establishing new types of female beauty, or in experimenting with forms of sensuous painting in which the narrative is subsumed by allusion, memory, or allegory. Thus, one of the book’s authors, Elizabeth Prettejohn, explores the extent to which artists of the Aesthetic Movement drew upon the styles and motifs of earlier eras (Ancient Greece, the Quattrocento, etc.) to create paintings that were full of associations yet ultimately ahistorical and enigmatic. She concludes: ‘visually and intellectually, the pictures stimulate rather than satisfy desire.’

The essays are grouped into chapters, which are arranged in a broadly chronological order. Commencing with ‘Literature’ and ‘Painting’ (as well as essays on aesthetic photography), the scope of the discussion then widens to address ‘The Palace of Art’, and the activities of artists, collectors, and their houses. This is followed by the furnishing of the aesthetic interior (with marvellous individual essays on wallpapers, textiles, ceramics, and metalwork); the world of the ‘greenery-yallery’ Grosvenor Gallery (including such fascinating subjects as artists’ frames and Whistler’s exhibition spaces); and then the intersection of aestheticism and the marketplace, which ranges from women’s dress and jewellery to the satirical magazine Punch, and Gilbert and Sullivan’s Patience. The concluding chapter investigates the decade of the 1890s, reconfiguring it as a final creative flowering of Aestheticism rather than as an inevitable decline into parody and inertia following the disgrace and death of the movement’s great advocate, Oscar Wilde. Stephen Calloway, the editor and guiding spirit of The Cult of Beauty, makes a persuasive case regarding the essential continuity of ideas between the early period of the 1860s and 1870s, and the later so-called ‘Tragic Generation’.

The decision to publish The Cult of Beauty as a scholarly book, not a more traditional catalogue, has resulted in a major contribution to the field of study that will long outlast the life of the exhibition.

Comments powered by CComment