- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This book of essays by the vegan-anarchist-pacifist poet John Kinsella on the relationship between political activism and poetry raises two big questions: how do we live in modernity? and what is it like to live beyond the mainstream? The first question lies behind the great cultural movements of the West, from Romanticism to postmodernism. Whether writers have embraced modernity or rejected it, they have long struggled with the very conditions that brought literary culture into existence. The utopian possibilities of modernity have always been in conflict with modernity’s material realities.

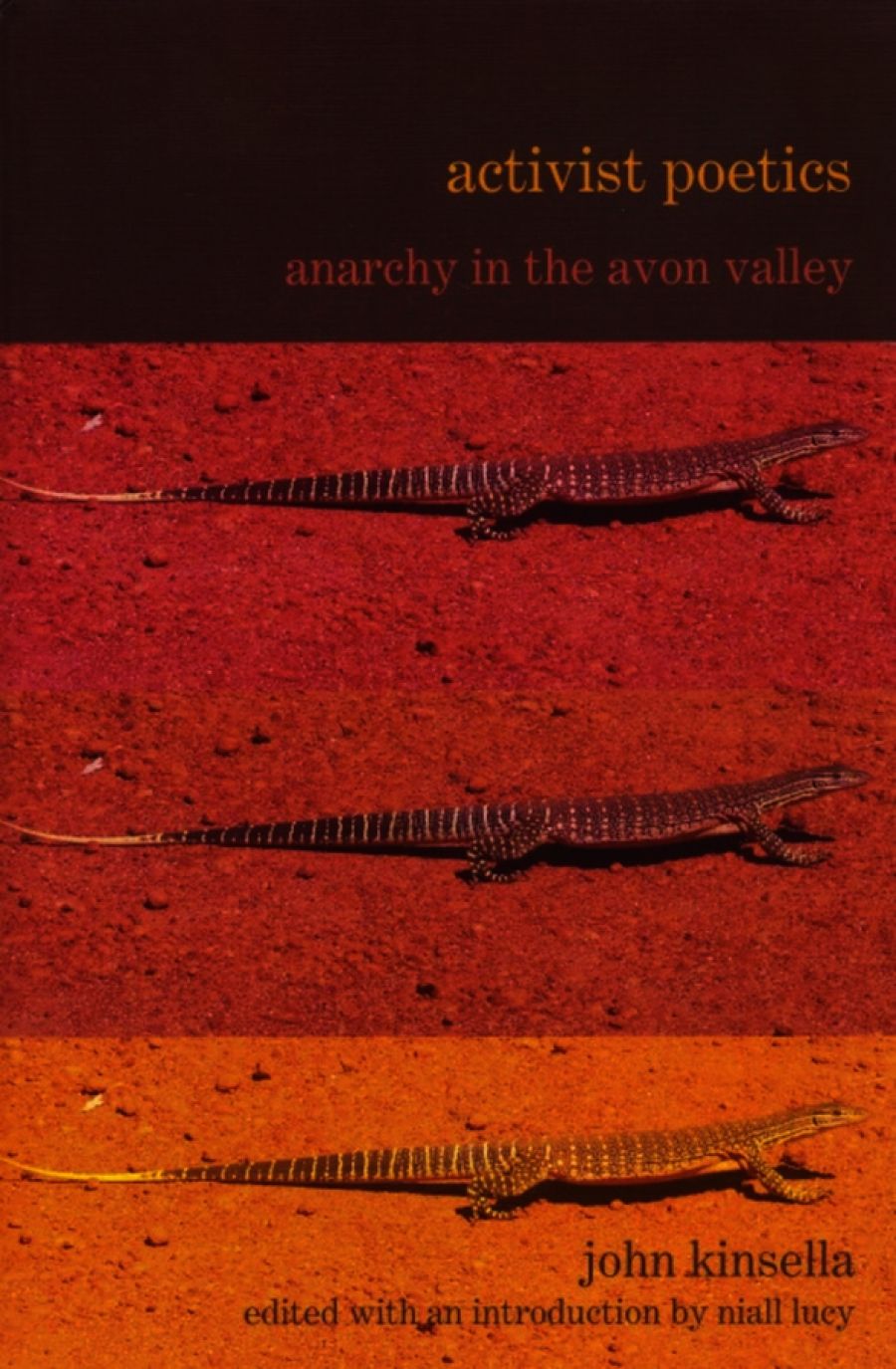

- Book 1 Title: Activist Poetics

- Book 1 Subtitle: Anarchy in the Avon Valley

- Book 1 Biblio: Liverpool University Press (Inbooks), $170 hb, 224 pp

Activist Poetics deals repeatedly with the ambiguous conditions of modernity and human society, showing how these two concepts are profoundly interdependent. The limits, or lack of limits, that we place on the development of modernity are clearly related to what we perceive as social goods. The degradation of the environment, the exploitation and harm of animals, and the systematic undermining of minorities’ rights (to name Kinsella’s major interests) can all be seen as effects of modernity and of a particular conception of society.

But all of this ignores the ambitious project at the heart of this intense book: to trace the relationship between political action and poetic speech. W.H. Auden has much to answer for with his gnomic observation that ‘poetry makes nothing happen’. (The phrase appears in an elegy, and while elegy cannot raise the dead, it certainly is a form of ‘emotional activism’.) Kinsella doesn’t fall for simplistic instrumentalist/aesthetic models of poetry. Rather, he traces the many complexities, ironies, and contradictions of writing poetry out of a profound desire to bring together one’s political and ethical beliefs and one’s actions. Actions, as Kinsella makes clear, can legitimately include creative practice. As he writes in the book’s opening essay, ‘“Environmentalism”, for want of a better word, is what I do in life and in my writing.’

One of the many implicit arguments in Activist Poetics is that poetry, being creative, is open-ended, and therefore its effects are open-ended. In this sense, the book is a theory of creativity as a form of playful opposition. Interestingly, this chimes with the view of the English psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott that the opposite of play (which is the basis of creativity) is not work, but compliance. Given the nature of politics and ideology, and the workings of the state, this insight gives creativity considerable political potential. Avoiding compliance involves spontaneity, originality, and subjectivity.

These three things are, indeed, the hallmarks of Kinsella’s book, if not his entire oeuvre. Kinsella’s engagement in Activist Poetics with modernity and society is not disinterested (that great facet of Enlightenment modernity). Rather, the book is marked by a profoundly personal engagement with the issues and ideas it raises. This personal engagement is not, however, a politically ‘weak’ position. As the book’s editor, Niall Lucy, states in the Introduction, ‘In its many eccentricities ... this book is not concerned to charm its way into readers’ hearts, but rather to find out who might have the mettle to bear witness to it’. Bearing witness is what Kinsella himself does repeatedly in these essays, which cover, among other things, pacifism, veganism, ‘Plagues and Bioethics’, ‘Refugees and Australia’, environmentalism and creative practice, poetry and justice.

A literary work’s originality can be measured by the difficulty we have in characterising it. This work is especially difficult to characterise. While Activist Poetics has been published by a university press, it avoids the usual procedures of a scholarly work: it is intensely subjective; sometimes prolix, sometimes casual in tone; and it can be funny (a feature of Kinsella’s work that seems to have bypassed a number of readers). Activist Poetics is also, unlike most scholarly books, unconcerned with hiding the exigencies and occasions of its composition. The essays routinely quote from Kinsella’s emails, journals, blog, letters, and poems. All of this is consistent with Kinsella’s valuing of spontaneity and energy, as well as with the importance of the particularities of a given locale (‘context’ being the textual equivalent of locality). Readers who find Kinsella’s self-quotation ‘self-indulgent’ or unscholarly have seriously missed the point of this book.

Lucy characterises the essays as testimonials, closer in spirit to the apologia than the manifesto. As he writes, the apologia ‘asks not that we take “action”, although of course it doesn’t preclude us from doing so. It asks, rather, only for our countersignature.’ Although the apologia has strong links with religious discourse, one of the strengths of Activist Poetics is its avoidance of dogma and stridency (that is, the rhetoric of compliance). Kinsella’s account of living in modernity and refusing to live in the ‘mainstream’ is compelling for the humane, detailed way that it is presented.

While Activist Poetics may be ‘unscholarly’ in the traditional sense, not least because it is written from a position of ‘interest’, it is far from anti-intellectual. Indeed, the book has an extraordinary intellectual breadth, with subjects ranging from animal rights and GM crops, to literary theory and local history. All of these aspects are seen, for instance, in ‘Half-Masts: A Prosody of Telecommunications’, an essay that ingeniously brings together the rhythm of radiation (the basis of wireless telecommunication) and the prosody of poetry.

Communication is ultimately what this book is about. Kinsella commonly refers to poems as setting up dialogues, and the book itself sets up possible ones. As with verbal dialogue, the book allows for readers to disagree with it or to find it unconvincing at times. It is appropriate, too, that the book ends literally with dialogue, as seen in the coda which incorporates the book’s editor into the body of the book itself, and two dialogues between Kinsella and his partner, the poet Tracy Ryan. Such an ending is wholly consistent with the book’s aims and draws attention to its already-dialogic condition through the inclusion of numerous notes by the editor that are interpolated into the text, rather than beneath the text asfootnotes, as is customary in academic works.

The book’s coda, ‘Visitors’, notes that Kinsella has been increasingly cutting himself ‘off from contact with the “outside world”’. In light of the book’s themes, such ‘cutting off’, as a narrative conclusion, could be viewed as a plangent, if not pessimistic, ending. But, as Kinsella relates, living near York, in Western Australia, with Ryan and their family, is a type of activism, a localism that is perhaps inevitable for someone keen to ‘opt out’ of the state (despite the fact that he continues to work for that state institution, the university). It is a strangely moving ending.

Modernity, as Kinsella relates in Activist Poetics, is often seen as a force that annihilates distance. Kinsella seeks to recognise those ‘annihilated’ distances. In part this is to recognise the rights and histories of those ‘others’ who occupy those spaces. But there is another aspect to this project of recognising distance. Modernity, the annihilator of distance, also requires distance to allow its ‘darker’ workings to continue. Hence, animals are slaughtered out of sight, consumer goods are produced in unknown conditions in unknown places, and the state does its work with as much secrecy as its citizens will tolerate. It is not easy to look at the slaughterhouses, the detention centres, and the laboratories of modernity, but it is important that we remain aware of them. Otherwise, modernity and the society it creates may well destroy us. If Kinsella feels like this, too, it is to his credit that his work is as humane and playful as it is.

Comments powered by CComment