- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Journals

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Special issues are difficult and delicate, given the burden of representation. Editor David Brooks confesses to providing only a glimpse of the rich field that might constitute Indian–Australian literary relations. He offers ‘that very Australian thing – a showbag, a sampler, full of enticements to explore further’. Given the slow but steady realisation in Australia that India should be a focus of attention for its scholars and students, this is a timely attempt.

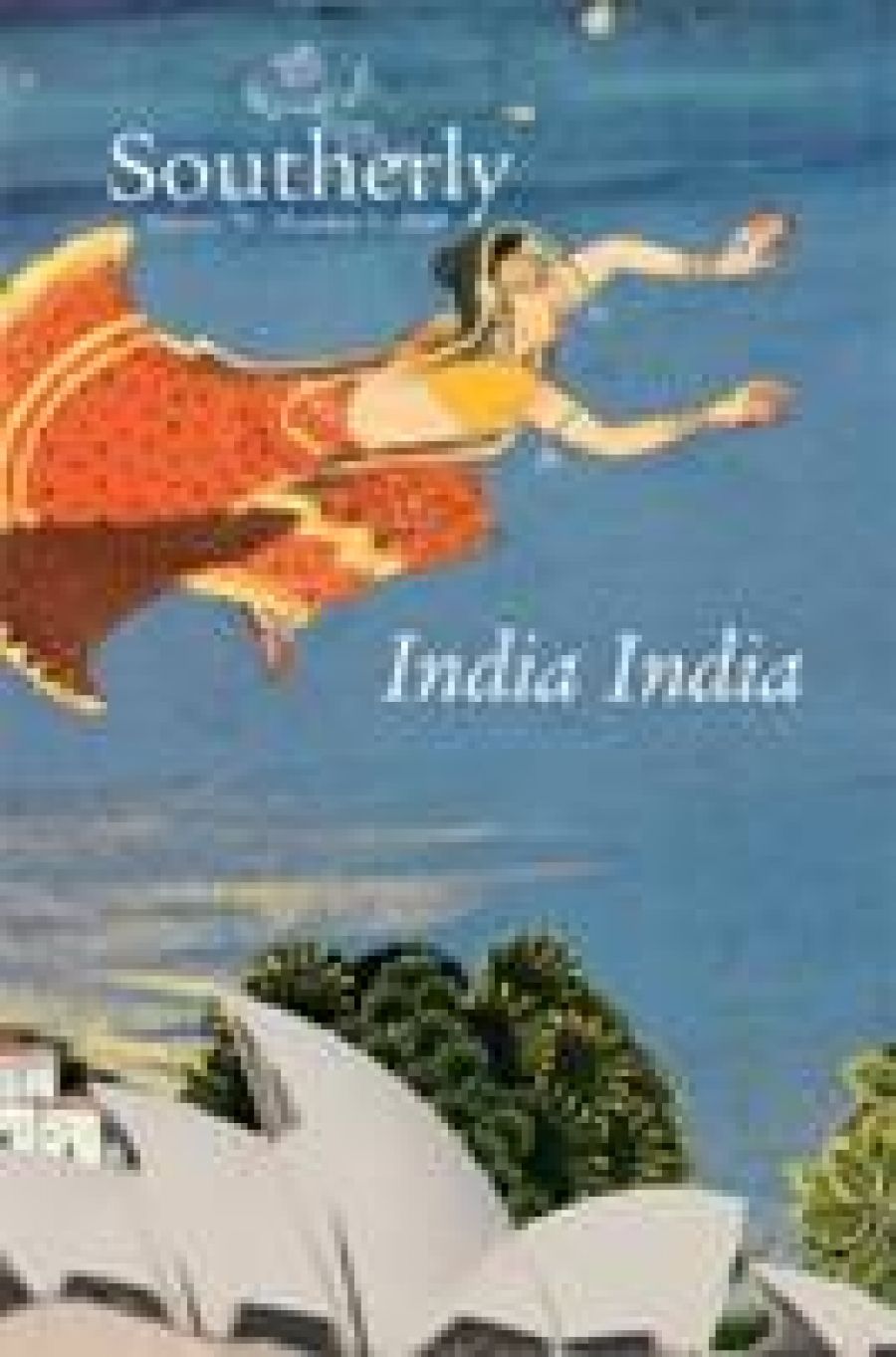

- Book 1 Title: Southerly, Vol. 70, No. 3

- Book 1 Subtitle: India India

- Book 1 Biblio: Brandl & Schlesinger, $29.95 pb, 282 pp

Enticing and evocative, the cover showcases a detail from Amardas Bhatti’s 1830 Folio 19 (Suraj Prakash) from the Mehrangarh Museum Trust. It offers a version of synthesis: the vignette from Jallandharnath and Princess Padmini Fly over King Padam’s Palace shows Princess Padmini flying over Australia’s iconic Opera House instead of the royal swimming pool in Jodhpur. The words ‘India India’ inscribed beneath her flying body leave it unclear as to whether she is flying away from or towards India. Such a vision provides an apt metaphor for the entire volume, in which contact between the two nations is an ephemeral thing. Any landing can only be a matter of chance, and what you discover in the land, an instance of luck. The works, both creative and critical, offered in this volume, have something of the flavouring of this serendipity.

Despite its theme of Indian–Australian literary relations, most of the strong pieces here are concerned with the matter of Asian-Australianness, with reference to the specific case of India. Paul Sharrad’s excellent essay, ‘Reconfiguring “Asian Australian” Writing: Australia, India and Inez Baranay’, comprehensively maps this area and confirms my own suspicion that what we might count as Indo-Australian writing can be numbered on ten fingers, and in fact does not yet constitute a field of study per se. This depressing fact is brought home by Sharrad’s analysis of Australian writer Inez Baranay, whose writing he sees as doing transnational cultural work within Asian spaces. Without disagreeing with his point about the impossibility of cultural purity in an age of global flows, I would argue that transnationalism becomes meaningful only when there is a sharper understanding of what resides within the national spheres. Such a specificity of the national becomes evident in the comparative frame provided by Maria Preethi Srinivasan in ‘Constructing Aboriginal and Dalit Women’s Subjectivity and Making “Difference” Speak’. Bringing together the life writings of Jackie Huggins with Bama and Kumud Pawde, Srinivasan, despite her gesture towards a desired political transnationalism, demonstrates that even as the category of Dalit/Aboriginal provides an international momentum for mobilising, the specificity of their sites cannot be denied. This specificity is brought home in K.G. Naga Radhika’s ‘Presenting the Past: Historiography in Aboriginal Theatre of the 80s and 90s’. The egregious mistake of finding a transnational parallel to every national issue is nowhere clearer than in Patrick Bryson’s clumsy attempt to make sense of the controversy about Indian students last year in ‘The Men who Stare at Bogans’. Given the substantial body of nuanced work that has been done in Australia on this issue, it is a pity that this ham-fisted, politically confused piece mars the intent of the volume. But Mark Macleod’s ‘Reading My First Time in India’ not only makes up for this shortfall, but also provides a much more expansive and historical understanding of what Australian–Indian literary relations might look like.

The creative pieces by Australian and Indian writers further reinforce these parallel and divergent modes of expression. The five contemporary Indian poets, Arundhati Subramaniam, Keki N. Daruwalla, Meena Kandasamy, Priya Sarukkai Chabria, and Temsula Ao, represent the best in subcontinental poetry, but they are not evidence of Australia–India relations, literary or otherwise. Similarly, Australian poems by Richard Deutch and Craig Powell are affecting. Only Judith Beveridge and Philip Salom poignantly cross borders, each hailing an Indian counterpoint. While it might be difficult to categorise poetry so stringently by national borders and concerns, the prose pieces attest definitively to their Australian domicile. Especially strong are the short stories by Christopher Cyrill and Kunal Sharma. Chris Raja’s strange story has an abrupt feel to it, while Aashish Kaul’s lingers too long over its own pretensions. On the whole, we are left longing for more, and are told that we have more to discover in the online component, The Long Paddock.

I started this review by reiterating the impossibility of representativeness. At the end of my sampling, I am prompted to ask these questions: what constitutes Indian–Australian literary relations? Does it inhere in the content of specific bodies of work or particular signifiers such as the names and professed interests of the writers? Does it lie in a kind of domicile that might evoke reactions and responses to social issues and political events in the respective nations? Or is a literary relation solely the purview of academic conferences of the kind referred to by Brooks, where Australian Studies of the offshore variety far outnumber the strength of the field in this nation itself? If there are indeed even ten thousand students of Australian Literature in India, it may be time to ask how many students of Indian Literature there are in Australia. At the Indian Association for the Studies of Australia, Eastern Region, in Kolkata 2010, someone remarked on the deluge of presentations on Australian literature, but traffic the other way was remarkable only for its absence. A literary relationship is a two-way street. Southerly has made a tiny, timely attempt to address it.

Comments powered by CComment