- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Herz Bergner arrived in Melbourne in 1938, having left Warsaw after Hitler’s rise to power. Already a published Yiddish short story writer, he joined a group of progressive Yiddish-speaking writers and thinkers who often gathered at the Kadimah Library in Carlton. As information about the Holocaust began to reach these shores, Bergner argued passionately for an increase in European immigration to Australia. He also began work on a novel in Yiddish about a boatload of Jewish refugees (and some others) adrift on the high seas, supposedly destined for Australia.

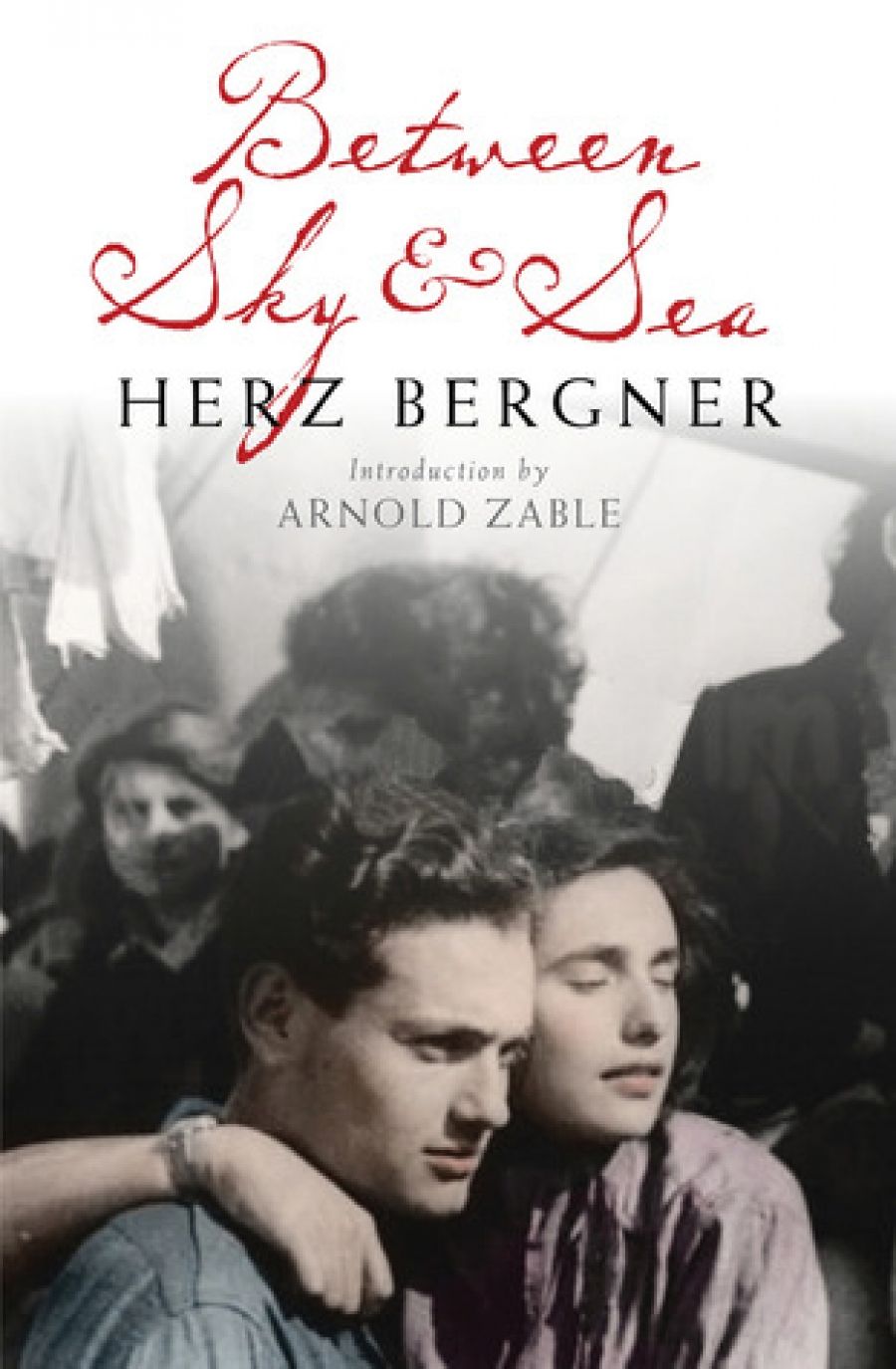

- Book 1 Title: Between Sky and Sea

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $27.95 pb, 240 pp,

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/MJ0bo

That novel was translated into English, in consultation with Bergner, by Judah Waten. As Arnold Zable points out in his valuable introduction to this new edition of the novel, Between Sky and Sea (1946) is among the earliest fictional representations of the Holocaust. It is also a fine work of art, which won the Australian Literature Society’s Gold Medal.

Set at an unnamed time during the Holocaust, the novel contains many scriptural and literary echoes. There is a Noah among this group of drifting refugees, but he is a revolutionary who has traded the Jews’ belief in the promises of deity for the Marxist faith in the consolations of history. A closer narrative parallel – the ‘Ship of Fools’ – lurks in the book’s vein of black comedy, as when a self-preening Jewish lady exerts her charms in an unavailing effort to win the captain’s sympathy for the group. As Zable notes, an all-too-real historical precedent of which Bergner would have been aware was the fate of the St Louis, which left Germany with over nine hundred Jewish refugees aboard. The boat was turned away from Cuba, the United States and Canada before finally docking at Antwerp. Two hundred and fifty of its passengers died in the Holocaust. Zable rightly insists that Between Sky and Sea has urgent relevance for an Australian community enmeshed in often brazenly politicised debate about ‘boat people’. Fittingly, this Text reissue was launched on World Refugee Day at the Kadimah Library, now located beside the Jewish Holocaust Museum and Research Centre in Elsternwick, Melbourne.

The benighted group aboard ‘the old Greek tramp steamer’ manned by a largely anti-Semitic crew includes religious and secular Jews, folk reeling from the Holocaust trauma and a Greek Gentile who communicates to the Jews his sense of a shared destiny, ‘“me and you, one fate”’. Conditions on board are dreadful, especially when typhus makes its appearance. Reactions to what feels like ‘a journey without end’ vary according to individual history, temperament and luck. Bergner, who knew the sea from his own voyage to Australia, writes superlatively about its moods, beauties and terrors. Here is the sea as witnessed by Ida and Nathan, star-crossed lovers pursued across the oceans by Holocaust trauma:

On moonlit nights they would sit together looking at the water and watching the moonlight break over the waves like fragments of white glass, then pour like molten silver into the depth of the sea. Even when the sea was stormy and raged, opening great chasms, tossing the ship from side to side and covering it with foaming water, they would not retire to their cabins. They remained in a corner and watched how it became suddenly dark. A mist spread over the sea, joining it to the sky in a blanket of haze.

There is a touch of the Romantic Sublime here. But this is not just the sea; it is Ida and Nathan’s sea, the moonlight the setting for the romance that these people cannot have, even in this extremity, because of the extremity that they have endured before and during the Holocaust. When, just once, they are intimate, Ida’s lips are ‘twisted with pain and desire’. At the story’s end, ‘The sea shouted with triumph, hurried and bellowed, slobbering with joy as though satiated after a wild, drunken orgy’. In this pogrom-like murderousness, the sea is a place where the fierce power of nature and the malign impulses that are in the human animal fuse, rather as the mist fuses sky and sea, incarcerating the travellers in what is, in many ways, a floating concentration camp.

As the narrative unfolds, we become deeply acquainted with Ida and Nathan in the narrative present and also through vivid, empathetic recounting of their pasts. These alternations of present and past, which Bergner employs for most of the cast, achieve a remarkable sense of individual psychological depth within a chronicle of collective crisis and misery. If we were to picture Yiddish fiction as a spectrum with psychologically stereotyped stock characters at one end, and deep psychological evocation of individuals at the other, Between Sea and Sky would sit well towards the latter end. Bergner’s Romantic Sublime subserves a nuanced psychological realism.

It is principally Bergner’s mastery of narrative point of view that enables him to bring his characters so vividly to life while at the same time tracking the group’s fragile dynamics, its oscillating moods and shifting patterns of conflict and alignment. His omniscient narrator seldom editorialises, but rather glides between the consciousnesses of various characters, sometimes even unveiling their sketchily imagined antipodean futures. There is special artistry in these shifts of narrative and temporal focus, in the movements between in-depth and more superficial psychological description, and between writing the individual and writing the group. At moments of crisis or hope, individual viewpoints can coalesce, the group becoming a kind of chorus reflecting upon its own haunting fate. Bergner writes with subtle insight about how extreme stress unites or divides the group, as when a sense of deep foreboding returns after a period of misguided optimism.

They felt towards each other a deep intimacy, a kinsmanship that could never be disturbed, a love that streamed from the depths of their hearts. They were again one big family with the same sorrows and aspirations.

The chemistry between the group and the individual is described after Fabyash, a tormented soul who had alienated the others through an earlier and serious misdemeanour, commits suicide.

More than one man had disappeared in broad daylight, yet no one was missed as much as Fabyash. They were so used to him. Just as at the beginning of the journey they had become accustomed to his alarms and warnings, so too later they had grown used to his silences, his self-torture and his avoidance of everything. His melancholia had been like a loud cry that demanded a response from everyone.

The flashbacks to Fabyash’s past provide a context for his earlier shocking deed, and it is everywhere understood in the narrative that trauma – let alone repeated experiences of trauma – can have corrosive moral effects. Bergner is no sentimentalist. He makes no bones about the moral frailties that emerge on board this wretched boat. He does not pretend that history’s victims are sanctified by their fate. Nor does he overlook the subtle movements of the heart, the abiding traces of decency and solidarity, that can momentarily redeem a situation such as this. After a bitter dispute two mothers lay down their arms. One, seeing that the other harbours no bitterness, ‘trembled as if she were caught in a theft. She was terribly ashamed that she had harboured such ugly thoughts when the other woman was so good and so free from evil.’

In the end, though, fate does not dabble in moral discrimination. Writing at a vast and guilty geographical remove from the Holocaust, Bergner fashioned a version of Apocalypse, and in doing so he turned to an uncompromising literary realism that he hoped might at least begin to tell the awful truth.

Comments powered by CComment