- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Everyone, I suspect, has a favourite photograph by Henri Cartier-Bresson. Mine shows two couples picnicking beside what I have always thought was the Marne River but turns out to be somewhere else altogether. Juvisy (1938), as it is now titled, depicts urban workers relaxing near a man-made pond in the suburbs of Paris. This is indicative of the exhaustive research of Peter Galassi and his colleagues, who have brought to light a huge amount of new information on Cartier-Bresson and his photographs. Their book has been published to accompany a Cartier-Bresson exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, where Galassi is chief curator of photography.

The book isn’t shy about scholarship and makes extensive use of the archive at the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson in Paris, established by Cartier-Bresson’s widow, Martine Franck. Galassi’s essay isn’t always easy to read, due to the inclusion of voluminous amounts of detail. However, its seriousness and ambition are welcome, given the current proliferation of illustrated books with short texts. There are 217 footnotes and more than eighty pages of reference material that outline, among other things, Cartier-Bresson’s travels, month by month. These journeys are also represented in the form of maps, which are fascinating to scrutinise.

Henri Cartier-Bresson was a son of the grande bourgeoisie. His family made its wealth manufacturing and marketing coloured sewing thread. Cartier-Bresson had everything going for him: wealth, good looks (an ‘almost feminine beauty’), intensity, intelligence, and an extraordinary range of connections. He wanted to be a painter and showed Gertrude Stein his attempts (she advised him to join the family business); read widely from Rimbaud to Joyce; played a minor part as an English servant in Jean Renoir’s film The Rules of the Game in 1939 (the film was shot in a chateau owned by Cartier-Bresson’s father); flirted with surrealism; published his photographs anonymously in the communist daily newspaper Le soir (he never actually joined the Communist Party); made films in support of the Spanish Republic, and so on.

Cartier-Bresson lived through difficult times. One of two million French soldiers captured by the Germans after the outbreak of World War II, he spent three years in forced labour before finally escaping on his third attempt. It was after the war that his career took off. Like his co-founders of Magnum Photos, he benefited from the proliferation of picture magazines and from the appetite for topical material. His work from India, Indonesia, China, the USSR, the United States, and Europe was published in the leading picture magazines of the day.

Galassi’s concern is with Cartier-Bresson’s creative genius and his stature as an artist, but frustrations and disappointments flicker through his narrative. The archive itself poses difficulties due to its size (14,000 exposures from three decades) and irregular quality. Galassi struggles with what he describes as the ‘vast, uneven, perpetually protean’ body of work that Cartier-Bresson left behind; this reveals a great deal about his MoMA training and the limitations of connoisseurship. What worries Galassi most is the un-preciousness of Cartier-Bresson’s approach, the fact that he showed a ‘disinclination’ to take control of all aspects of the photographic process. His energy went into the taking of the photograph, not its printing or presentation, which after the war he mostly left to others. This had some conspicuous successes, notably his first two books of photographs, Images à la sauvette (1952), with a cover by Henri Matisse (the English edition was titled The Decisive Moment), and Les européens (1955). But Galassi argues that Cartier-Bresson’s lack of interest in creative control meant that he was often not well served by his collaborators. As a consequence, his work did not achieve its full potential.

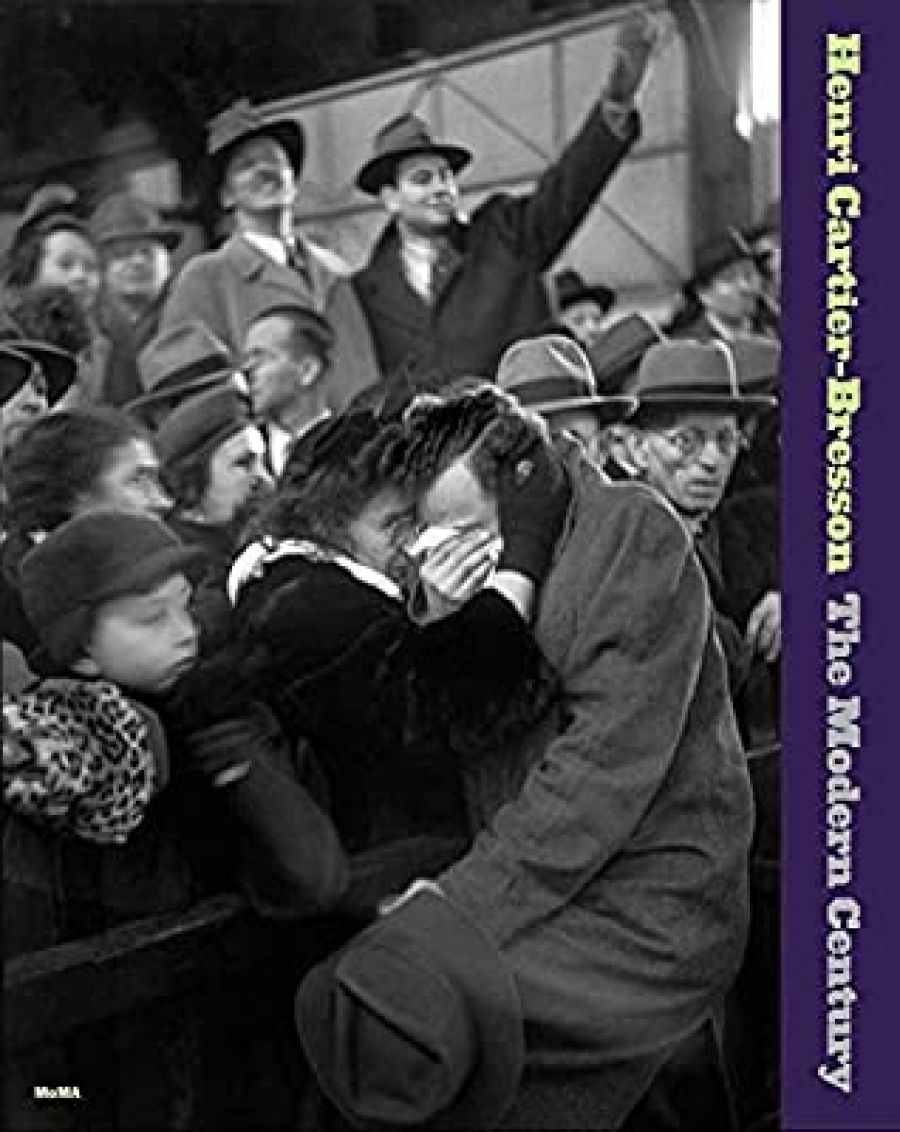

Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Modern Century is lavishly illustrated, and the quality of the reproductions is outstanding. Many previously unseen photographs are included, along with the classics. The majority of plates are in the category of reportage, drawn from Cartier-Bresson’s prolific career as a photojournalist. Galassi’s claim is that Cartier-Bresson’s deepest sympathies were with the ‘age-old patterns of life’: that is, with the old world rather than with the new industrial one. However, he was working during a time of rapid modernisation, especially in Asia, and successfully documented its effects on ordinary people. The most impressive features of his style are its economy of means and a lyricism that comes through the use of a simple, energetic geometry.

I was also struck by Cartier-Bresson’s skills as a portraitist (there are at least one thousand portraits). He photographed some of the most famous figures of his day – philosophers, writers, artists and so on – and avoided the slickness and superficiality that characterised so much mid-twentieth-century celebrity portraiture. The portraits are distinguished by their individual distinctness and their liveliness. Like his strongest reportage, Cartier-Bresson’s portraiture displays an elegant sufficiency.

Galassi’s writing is descriptive, and his essay is dominated by biographical detail rather than by ideas. Contextual material is also slender. More could have been said about the end of Cartier-Bresson’s interest in photography in 1975 and his decision to devote the last years of his life to painting and drawing (he died in 2004). While Cartier-Bresson emerges from the essay as a strangely free-floating figure, the reproductions attest to his extraordinary accomplishments. They alone will further elevate his reputation. The book has made me look anew at Cartier-Bresson’s photographs, already rewarding me with some new favourites.

Comments powered by CComment