- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

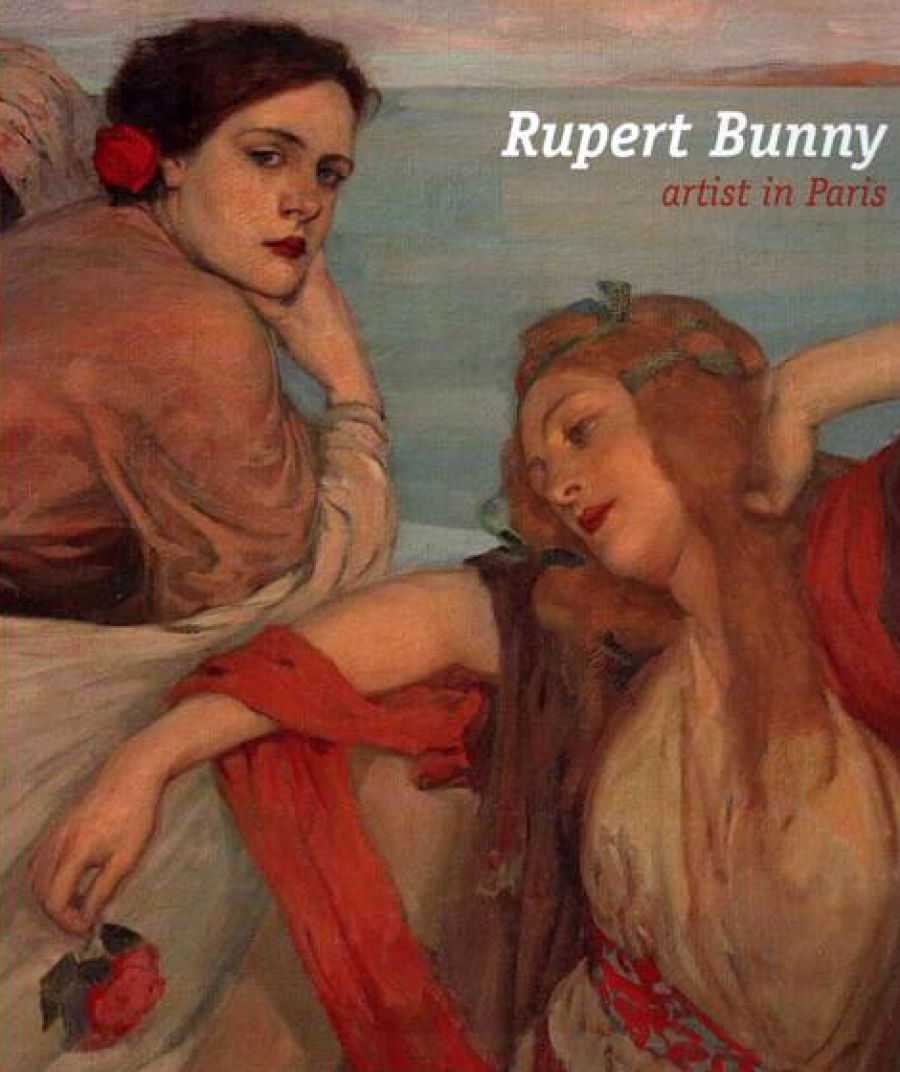

For those who saw the recent Rupert Bunny retrospective in Sydney, Melbourne, or Adelaide, where there were accompanying lecture programs, an informative audio guide, a lively children’s guide, and frilly knickers and parasols afterwards in the gallery shop, Rupert Bunny: Artist in Paris is a fine record of the exhibition. If you missed the show, this book provides a very good ‘virtual tour’, with works grouped both chronologically and thematically, all exhibits reproduced, plus full-page details of the artist’s fin-de-siècle beauties, decorative idylls and poetic mythological subjects. It is also a great deal more.

- Book 1 Title: Rupert Bunny

- Book 1 Subtitle: Artist in Paris

- Book 1 Biblio: Art Gallery of New South Wales, $65 pb, 224 pp

Bunny was Australian – born in Melbourne to an upper-middle-class English father and Prussian mother – and first trained as a painter at the National Gallery of Victoria’s school, with contemporaries including Frederick McCubbin, Arthur Streeton, Jane Sutherland, and the sculptor Bertram Mackennal. Bunny moved to London at the age of nineteen, and then to Paris, where he remained for most of the next forty-eight years, before returning to Melbourne after the death of his French wife in 1933. He reputedly turned down the offer of French citizenship at one stage, on the grounds that he would be considered an interloper by the locals and a deserter by Australians. While previous accounts of his career have usually aimed to locate the expatriate Bunny – often somewhat uncomfortably – within a narrative of Australian art, this book, produced as the exhibition catalogue but also an outstanding monograph in its own right, presents him unequivocally where he wanted to be – ‘in Paris’.

For Bunny, late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Paris was ‘the one place in the world to study for the man who wants to do really good work’. It was the centre of the Western artistic world. As he explained during his first trip back to Australia in 1911, nobody who has not lived in Paris ‘can have any idea ... of the intense vitality of art there. Out here … art is not the living, breathing thing that it is in Paris … Here art is an entity; there an atmosphere.’

Bunny’s greatest successes were international, rather than national; and in continental Europe, even America, rather than Great Britain. He never became Sir Rupert but he was a sociétaire of the New Salon, a sociétaire and juror for the Salon d’Automne, had thirteen of his works purchased by the French government, and was described by one Salon critic as un peintre des plus parisiens – ‘one of the most Parisian painters’. Much of the popular appeal of the recent exhibition probably lay in Bunny’s European-ness (for gallery-goers who had already enjoyed such exhibitions as Masterpieces from Paris at the National Gallery in Canberra or the Frankfurt Städel Museum’s Impressionist and post-Impressionist paintings at the National Gallery of Victoria). A great deal of the interest of this book lies in the rich international context it provides for Bunny’s life and work.

The authors make an expert team, led by Deborah Edwards, Senior Curator of Australian Art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and curator of the exhibition. They draw on, fully acknowledge and discuss in some detail earlier research and writing on Bunny, notably David Thomas’s 1970 monograph and Mary Eagle’s exhaustive 1991 study of his paintings in the National Gallery in Canberra. The bibliography is excellent. They document and reproduce more than 130 works (although they also estimate his total output at some three thousand!). Many contemporary reviews are translated from French, and, most excitingly, Eniko Hidas, archivist in the AGNSW Library, has translated the journal of Bunny’s Hungarian novelist friend Zsigmond Justh, the only known record of the artist’s crucial early years in Paris. Now we know that the studio he shared with an aristocratic English painter, Alistair Cary-Elwes, was furnished not just with oriental carpets, daggers, fans and an upright piano (both were accomplished musicians), but also with a blue cloth tent – ‘This is where the artist lives’. Now the evocative but enigmatic photographs of Bunny with Cary-Elwes and a series of handsome young men in the late 1880s come to life. And who could forget Justh’s descriptions of the young Bunny, ‘six foot tall [with] curly blond hair, pointy blond beard and moustache (in the French style) ... and congenial’; or, at a masked ball, ‘dressed as an angel, wearing a white, semi-transparent, Indian-voile floor-length shirt ... a big bronze halo, and holding a six-foot-long trumpet’. At last the reason why Bunny’s paintings are held in a number of Hungarian museums makes sense: he went there at least five times.

Rupert Bunny and friends c.1887–88

Rupert Bunny and friends c.1887–88

Justh lists the artists and writers he believed had most influence on Bunny, including the ‘pre-Raphaelites, Swinburne and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Giotto, Fra Angelico, Bellini, the Spanish school, Leonardo and Titian’. Deborah Edwards explores Bunny’s eclecticism in far greater depth (possibly more than a non-specialist reader needs in order to enjoy Bunny’s art), teasing out the origins, evolution and importance of his various large thematic series of paintings more comprehensively than has been attempted before. She addresses the question posed by a writer for the Bulletin soon after Bunny died: ‘He did well: but did he do distinctively?’ Clearly, Bunny followed his own credo, that an artist ‘should paint only what appeals personally to himself’, with distinction, energy and a willingness to reinvent his practice. Even in old age, respected by younger Australian artists and elected first vice-president of the Contemporary Art Society in 1938, he was described as ‘one of the few painters of his generation whose personality has remained youthful enough to absorb fresh theories and new influences’. Edwards also considers the potential perils of expatriation – as judged at the time and by posterity – applicable not only to Bunny but quite possibly also to some twenty-first-century artists seeking reputations in the international sphere. Expatriation gave Bunny (as well as Edwards’s previous research subject, Mackennal, and, similarly, the hundreds of American artists working in Paris in the same decades) firsthand experience of the European avant-garde, but brought with it ambitions that grew into resistance to the risks in being avant-garde oneself. As she concludes, ‘It is a further irony that when success and honours from the European establishment did come to expatriates, questions were raised in the artists’ own countries about the validity of their art in national terms.’

Denise Mimmocchi, Assistant Curator of Australian Art, writes on Bunny’s colour monotypes, one-off impressions printed in oil paint that are arguably the most daring and innovative works in his oeuvre. Anne Gérard explains the Parisian artistic context: the Salons, the academies, the system of government patronage of which Bunny was a beneficiary. David Thomas revisits Bunny’s treatment of landscape, from cool Breton seasides around 1900 to almost Fauvist colour schemes influenced by the Ballets Russes; and Simon Ives and Andrea Nottage take us for a brief but fascinating visit to their conservation studio to investigate the artist’s choice of pigments. Finally and very usefully, there are maps showing studio addresses in Paris and painting spots elsewhere in France; thumbnail reproductions of the works still extant in French public collections; and an index. There is even the promise of more to come, with plans for an expanded catalogue listing, complete with provenance and exhibition history, and also the possible translation of Zsigmond Justh’s 200-page memoir, to be available before long on the AGNSW website.

Comments powered by CComment