- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

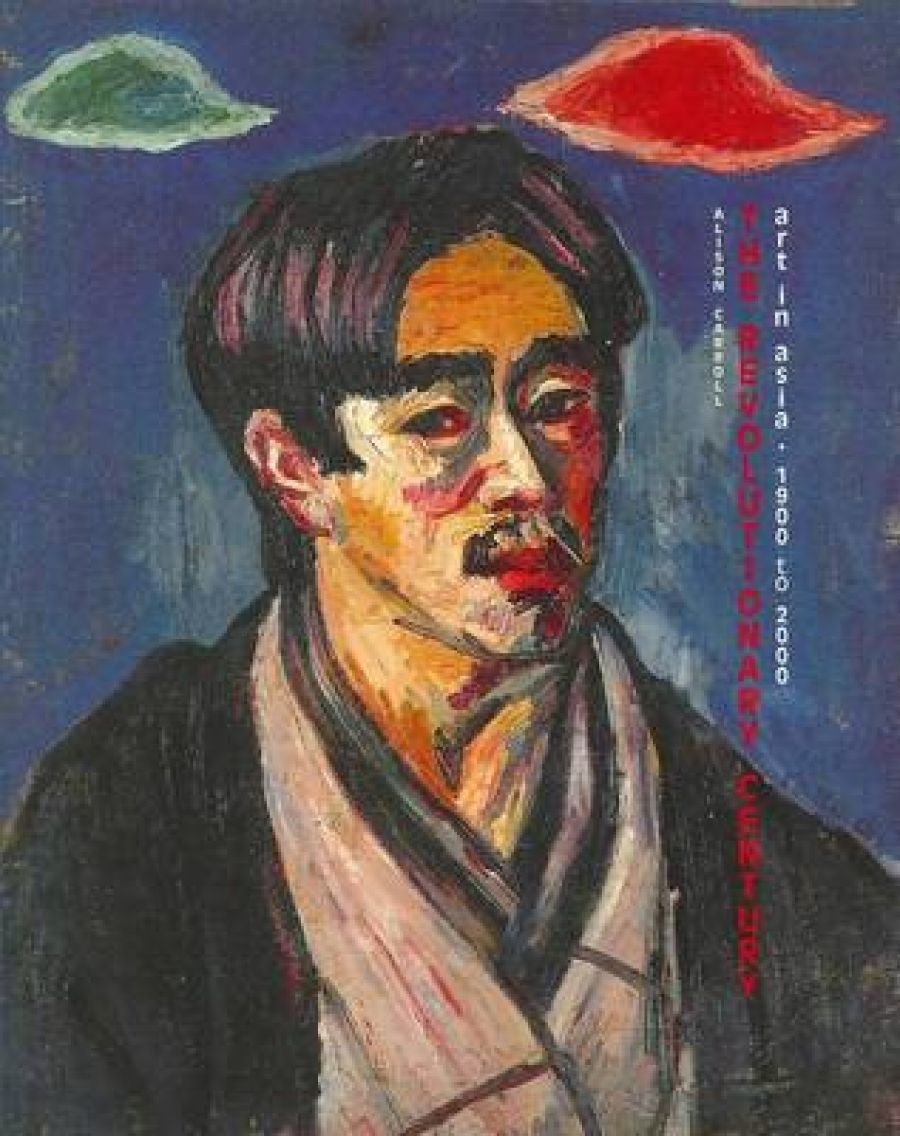

If you were to tell me that a book had been written that covered a century of art in Asia, from 1900 to 2000, and that its geographic range moved from Japan to Pakistan and Indonesia, to Nepal, the Australian outback, and Cambodia, I would initially ask how many volumes it contained. That such a book exists, in a fairly slim volume, is tribute to the skills of its author, Alison Carroll. How has she done it?

- Book 1 Title: The Revolutionary Century

- Book 1 Subtitle: Art in Asia 1900–2000

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan Art Publishing, $99 hb, 208 pp

- Book 2 Title: Every 23 Days

- Book 2 Subtitle: 20 Years Touring Asia

- Book 2 Biblio: Asialink, 96 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_SocialMedia/2021/August_2021/META/page_1.jpg

‘In an introduction to a century lived by half the world’s population,’ she tells us, ‘I can only cite the impossibility of fairness to all areas, and declare a desire to focus on one special trend – of the new – to give readers a starting point from which to look further.’ Carroll is well placed to do this, having worked in Asia for twenty years as the initiator of the Asialink Arts Program across eighteen countries in the region. Her practical experience is supported by two degrees in art history from the University of Melbourne.

Various aspects of ‘the new’, both in terms of form and content, are examined across five chapters, taking us from Japanese modernisation through Mao’s China and on to India’s ‘continual narrative’. Much of what is put forward as new is, of course, only new to that region at that time. We see Impressionist techniques introduced many years after the original Impressionist breakthroughs, and Fauvist colour choices made many years after Matisse and Derain’s personal revolutions. But this is how new knowledge spreads within the visual arts, and it doesn’t matter if it is picked up in Korea or Chicago; what matters is that it is picked up, developed, and superseded.

Stuart Davis was one of many who underwent a Pauline conversion at the Armory Show, held in New York in the spring of 1913. The best of the current movements of the School of Paris toured from New York to Chicago and Boston. At that time, America looked to Europe for its lead, in the same way that many countries later looked towards America, and arguably now look towards Asia. In his autobiography of 1945, Davis wrote:

The Armory show was the greatest shock to me – the greatest single influence I have experienced in my work. All my immediately subsequent efforts went toward incorporating Armory show ideas into my work … it gave me the same kind of excitement I got from the numerical precision of the Negro piano players in the Negro saloons and I resolved that I would quite definitely have to become a ‘modern’ artist.

The beauty of Carroll’s book is the way it shows how these instances of significant cultural exchange happen in a two-way street. Carroll gives us the reaction of the Chinese court painter Zou Yigui to Western art when it was first introduced to China:

The Westerners are skilled in geometry, and consequently there is not the slightest mistake in their way of rendering light and shade and distance … When they paint houses on the wall people are tempted to walk into them … But these painters have no brush-manner whatsoever; although they possess skill, they are simply artisans and cannot consequently be classified as painters.

We travel on through the twentieth century and see the true fruits of what I call ‘synthetic modernism’, that heady mix of the most tenable aspects of modernism and postmodernism, of region and centre. Many artists and individual works of art will be familiar to Australian gallery visitors from installations at the Asia Pacific Triennials in Brisbane or from Venice Biennales, notably Xu Bing’s A Book from the Sky (1987–91) and Wang Guangyi’s Great Criticism – Canon (1992).

Many of these artists have exhibited internationally for decades; they include Japan’s Yayoi Kusamaand the late Nam June Paik, from Korea. The generation that came before them, in many countries, made art that reflected the techniques of Socialist Realism without always sharing the same ideology. As we see in the chapter ‘War and Nationalism: 1940–1960’, strong and challenging work was emerging from Ceylon, India, and Pakistan. In 1943 Zainul Abedin, based in Dhaka, was making graphic works such as Famine that were as emotive as anything produced by Käthe Kollwitz in the West. Behind much of this work, particularly that of the ’43 Group in Colombo, but really across the whole of Asia, there was a nomadic exchange of ideas and lifestyles, with many artists travelling to study in London at the Slade School of Art, the Royal College, or Chelsea School of Art.

Oh Yoon, Four Kinds of Body Systems, 1985, woodcut, 37 x 50 cm

Oh Yoon, Four Kinds of Body Systems, 1985, woodcut, 37 x 50 cm

Today, young Australian artists travel across our huge region, often to take up Asialink residencies. This great organisation, founded by Carroll, also has a touring exhibition program. Since 1990 it has seen the work of over six hundred Australian and Asian artists travel to over eighteen Asian countries, from Bangladesh to Hong Kong to Indonesia. As the title of this publication tells us, this equates to one exhibition opening ‘Every 23 Days’.

This publication, plump with figures and statistics, has the feel of a corporate business report – which in a sense it is – rather than of a reflective work of critical analysis. Many artists, curators, and host organisations are highlighted throughout the text. These include Brook Andrew, Gordon Bennett, Robin Best, Shaun Gladwell, David Griggs, Destiny Deacon, Fiona Hall, Akira Isogawa, Natalie King, Tracey Moffatt, Callum Morton, Tim Morrell, James Morrison, Patricia Piccinini, Gabriella Pizzi, Megan Kirwin Ward, Judy Watson, and Philip Wolfhagen.

Once past the introduction, the book is laid out in strict chronological order. This throws up some fascinating juxtapositions, the weirdness of which, for me, underscores the project’s twenty-year success. On page seventy, for example, we have the exhibition ‘From an Island South’, curated by Jane Stewart, who was then running the Devonport Regional Gallery in Tasmania. The photograph on this page shows Sean Kelly sitting beside a work of Julie Gough’s Return (2005) and discussing it with a group of gallery visitors in Lahore, Pakistan. On the facing page is the raunchy poster for Destiny Deacon’s Walk and Don’t Look Blak (2006) in which most of the text is in Japanese. This came from a partnership between the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, and the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography.

Between these two publications, we move from a time when artists worked in small groups, such as the Singapore Alpha Group, the Anak Alam Painters’ Commune in Malaysia, the ’43 Group in Colombo, and the Peasant Painters Commune in Xi’an (not all of whom are mentioned here, but they represent a ‘type’) to the present day, where organisations such as Asialink, curators, and host organisations are facilitators, working with artists in cultural exchange.

Carroll ends her introduction to The Revolutionary Century by stating, ‘This wider story is written here to start dialogue on a regional and contextual account. It does at times differ from “nationally” sanctioned stories. It is hoped it is the start of further discussion.’

Once you have read it, I suggest that you read all the catalogue essays for the Asia Pacific Triennials set up by Doug Hall and his teams of curators at the Queensland Art Gallery. Collectively, they too make a wide-ranging visual narrative for our region, and all deserve praise.

Comments powered by CComment