- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoirs

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

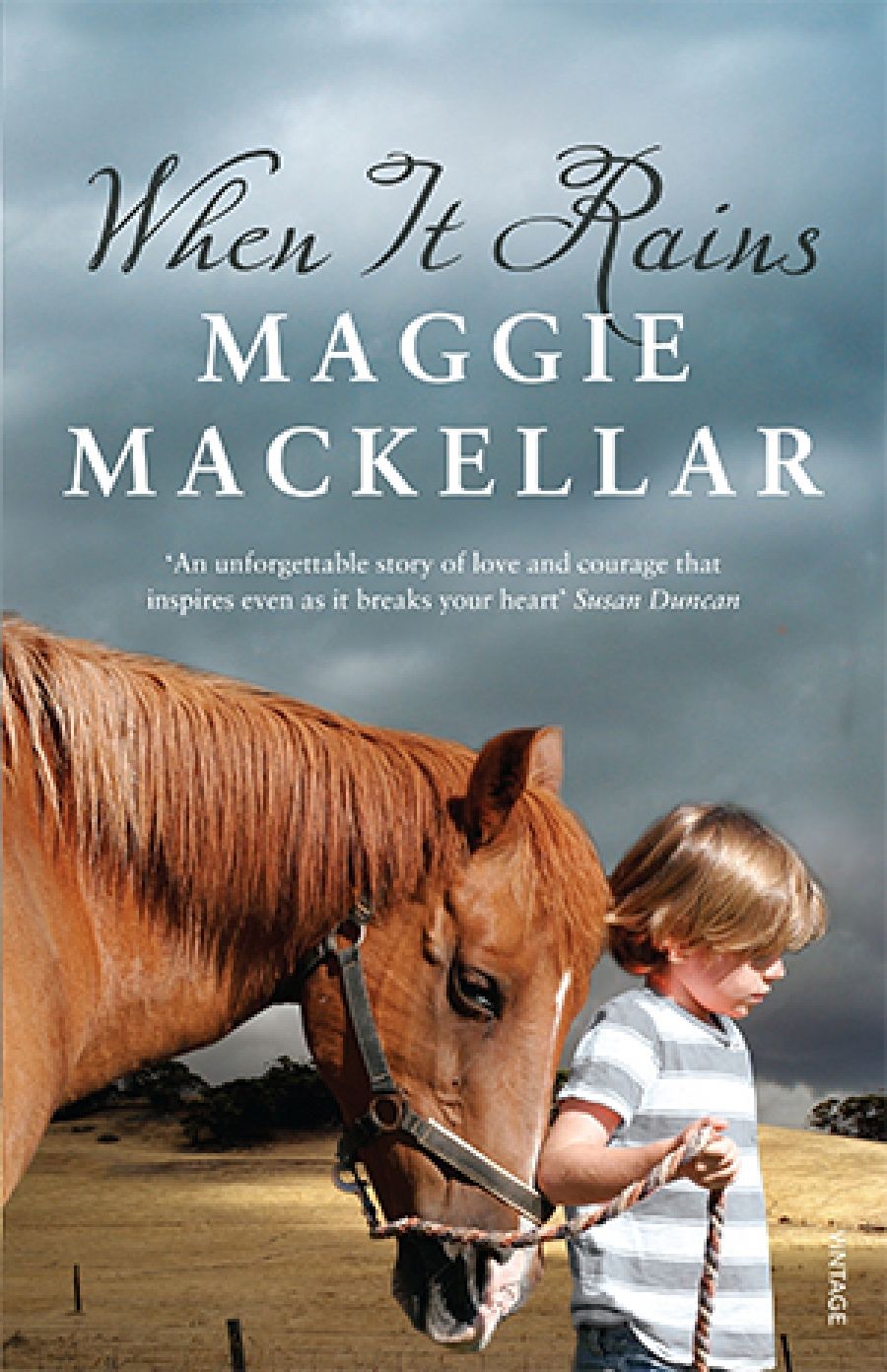

Maggie Mackellar’s stunning new memoir, When It Rains, narrates her journey through the disorienting landscape of loss and mourning. As a young academic, pregnant with her second child and uncomplicatedly in love with her athletic husband, the boundaries of Mackellar’s world seem fairly secure. With her husband’s sudden psychic disintegration and suicide, the foundations of that world collapse. She gives birth to a son, struggles to juggle single motherhood and an academic career, and, with her mother’s help, learns to appreciate small moments of beauty amid the pain.

- Book 1 Title: When It Rains

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $29.95 pb, 223 pp

Trusting her instincts, Maggie takes leave of absence from the University of Sydney and relocates herself and her children to her uncle’s farm. Here ‘[t]ime is slower, less painful’. Through their engagement with the rhythms of farm life, healing becomes possible. Then her mother is diagnosed with an aggressive cancer and dies within twelve weeks: ‘My body, suddenly, carries two stories of loss. I’m heavy with them, made cumbersome and slow.’

Mackellar’s writing about her body, and her mother’s body, is powerful and moving. The moments in which she nurses her mother are beautiful and intimate. The loss of her mother is crushing but familiar; that of her husband darker, more violent. Mackellar tries to make sense of it through fragmentary recollections, dreams, unanswerable questions. It is a story of enduring love and crippling pain. Mackellar rages against both losses; her anger drives much of the narrative with honesty and rawness. Despite her best efforts, she cannot separate the different experiences of loss. The narratives weave around each other, interweave:

My mother’s hands were sixty-four years old, weathered, beautiful. They were soft and hard and they held no duplicity of emotion. They didn’t love and hate. They were not tender and violent. They never offered me the world and handed me hell. They were constant: I miss them purely.

When it Rains is infused with longing and desire, as the epigraph of Cavafy’s ‘Return’ signals. The motif of return shapes the narrative on multiple levels: return to the farm, to trauma, to adventurous young love, and, above all, to absence. Maggie is not able to say goodbye to her husband. She cannot ‘participate fully’ in his funeral. He returns to her in charged, sexual dreams despite her efforts to peel him off her skin, to place him in the ground, to leave him undisturbed in his underworld.

Mackellar’s doctoral thesis and subsequent book Core of My Heart, My Country (2004) explore how pioneer Australian and Canadian women survived by adapting to their environments. It is no surprise that she undergoes a gradual transformation through returning to the country, to a working farm attuned to the rhythms of nature. She begins to relinquish her anger and grief, a release partly prompted by the creative process of writing. Mackellar cites Ann Carson’s suggestion that tragedy frames grief, thereby allowing its audience to experience vicariously trauma and darkness. But lived grief is not so easily contained. Neither does it end within a set time frame. Not wanting to be defined by grief, Mackellar asserts her agency and writes: ‘By writing, I risk sacrificing my deepest intimacies, but by writing, I control the shape they become.’

She is in control throughout. This is a highly literary, deeply structured, lyric work, yet it reads easily and honestly. Successful memoirs need to establish a sense of almost unmediated connection between writer and reader. Mackellar achieves this connection through her conversational tone, the truth of her anger, her self-doubts, her rhetorical questions and her extraordinary self-exposure. She is attuned to the charge of voyeurism sometimes directed at readers of memoirs, particularly traumatic memoirs, but she deflects the focus from the reader to suggest, via Susan Sontag, that she is also a voyeur of her own life.

Why write such a radically open memoir? Firstly, though she knows more than most that no one can prepare for grief, Mackellar offers readers an opportunity to experience with her some of its most intense, destabilising moments and to explore their personal responses to loss and mourning. Secondly, she asks us to bear witness to her story and to the restorative life she makes for her children. Thirdly, she invites us to stand with her in bearing witness to the lives and deaths of her husband and mother. Fourthly, this memoir is a love letter to her husband, her mother and her children and, for the children, it is a passing on of knowledge. Lastly, it is a way to say goodbye to her husband.

In his farewell to his great friend Emmanuel Levinas, Jacques Derrida demonstrates that language is always inadequate to the task of mourning. And yet we continue to strive for expression because part of our responsibility to those who have gone before us is to find a way to bid them farewell. When it Rains rises to this challenge and succeeds masterfully.

As Mackellar reaches some kind of equilibrium, the prose lightens; the word ‘happy’ sneaks into the narrative. Lottie, now nine, is suddenly ready to scatter her father’s ashes. They take them back to his beloved sea, the children ‘throw him into the air’, and ‘[h]e falls into beauty’. Then it rains. The rain signals new life, seasonal change, redemption, and hope. The parched earth breathes and releases its warmth. So too Maggie Mackellar is released, for now, from the constricting frameworks of grief.

Comments powered by CComment