- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Once in a seminar long ago, I heard Peter Steele quote one of Winston Churchill’s more disagreeable opinions, noting that Churchill was allowed to say such things ‘because he was Churchill’. This Churchillian self-definition, or certitude, or authority, or prowess, animates much of Steele’s own writings: Steele says this because he is Steele. Nor does he need to be disagreeable to do so.=

- Book 1 Title: A Local Habitation

- Book 1 Subtitle: Poems and Homilies

- Book 1 Biblio: Newman College, $39.95 hb, 168 pp

Importantly in the context, we need to balance this with another quote he used once in lectures, this time from the mouth of Benito Mussolini: ‘I have extinguished in myself all egoisms!’ Steele assumed, correctly, that his students would grasp the ludicrous pomposity of Il Duce, someone lacking in self-awareness. A second message, though, was that the ego is loose in the world, not least among writers, and what shall be done with it? One answer is literature.

‘For the canting psychopath flaunting a lousy haircut, / books in flames were just a beginning’, he writes of another person from that era, thereby finding good reason to persist with literature, for all its egoisms:

And if,

As we know, most of us, courtesy of the pages

Retrieved from rags or the skins

of beasts

Or sodden or beaten reeds, the hectoring

killer,

has comrades of a kind, the soul

hangs at times between hope and

despair, language

bringing its wounded self before us

to say that words are mummery in

the face

of the sword and the drone: and

yet, and yet

we know and they do not.

(‘Reveries in Lygon Street’)

Any child of World War II was brought up to remember his debts. These agreeable pages are full of what Steele knows, put out there that we might catch on.

Debt is frequently the secret behind a poem. The primary sequence of poems here are sonnets based on Gospel verses, little miracle plays that capture drama and signal beatitude. For those who are seasoned in the tough terms of these texts, Steele rewards with new angles. He is never more a companion than when pointing us down some road less travelled. He concludes a poem about the Passion, which he has the audacity to call ‘moron time’, with a scene of domestic harmony: ‘Inside, the governor’s reasoning with his wife: / Dreams, as he knows, have nothing to do with life.’ But for those who are new to this sort of thing, Steele gives something new out of something old. For example, in ‘Taste’:

His mother’s wisdom was to praise

their food,

That benediction from the hand of

God,

And so he found the coriander good

And blessed the little broad beans in

the pod.

It is said of Peter Porter that he never went to university, but gave everything he had back to it. Conversely, Steele used the university to give everything he could back to the world. This collegial behaviour is testament to the knowledge that one of the successful outcomes of a good education is an awareness of debt. Fortunately, this means there is plenty of fun in this collection. He opens a poem to Porter with the line, ‘It’s florets of thought that take the palm’, and, in an alphabet poem, exclaims, ‘O, as we say, for a few olives more / To oil us and spoil us and open the door’.

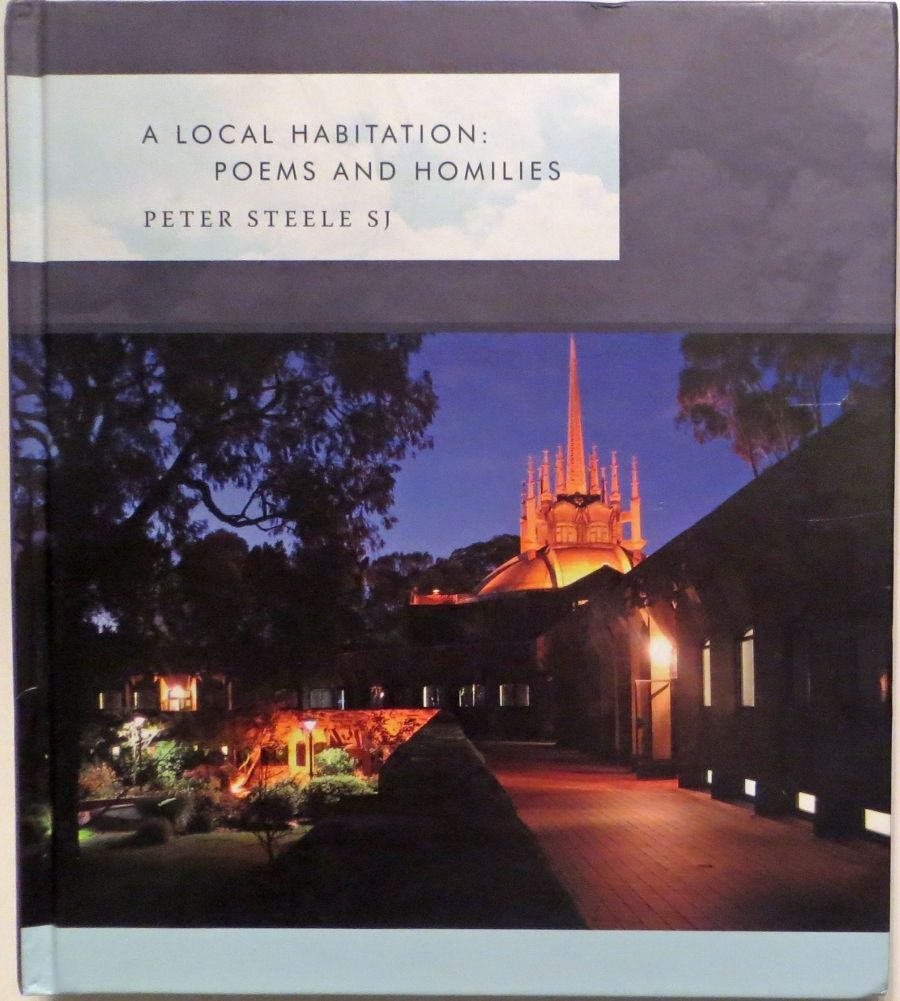

Newman College is the name of the local habitation of the title. It is the residential college in Melbourne maintained by the Society of Jesus, and it is the presiding genius of the book. The debt is mutual. We have many stylish photographs of the Griffins’ edifices, but, more meaningfully, pictures of the residents: intelligent young women and wide-awake young men; able scholars and wizened Jesuits. For this is Steele’s creative retreat, complete with its new library, one of those ‘inns for the mind on pilgrimage’.

The majority of the book contains one of the most under-published, if not precisely neglected, literary forms in Australian writing, and I don’t mean poetry, but the sermon. This is curious when you consider that a goodly proportion of the population listens to them every week. Homilies are one of the oldest forms in English, predating the novel, and Steele understands the measure of time. He is studiously normative in his use of Gospel, reminding us that in the Infancy Narratives ‘the surprise starts when … people realize that the shepherds are not there with a yarn: they are there with a revelation’. (Note too the quizzical use of the word ‘yarn’ in that sentence.)

Everyone has his or her favourite preacher, and it is easy to see why Steele is a favourite with many. He takes a common idea and puts it to the test. He hones down to his own short sayings. ‘Life’s retort against death is birth.’ ‘Whoever or whatever commands our time, does in effect command us.’ ‘God not only broke the mould when he made each one of us: he broke the palette.’ ‘What’s not to like about rainbows?’

Of course, the homily is made for community, not just for the ideal reader. Erudition plays second fiddle to clear message. Obscurity in a homily is as unacceptable as posturing or a grand leap. How blessed is Steele to have a bright congregation, ready for his gravitas and levitas.

Debt has been another way of explaining what is meant by that unpopular idea, sin. It means we owe things to others – an apology, a recognition, an introduction – and see others’ debts more quickly than we want to know our own. The homilist stands midway between the personal reparation that begins the Mass and the shared meal that is its purpose. Steele’s homilies frequently enact in words this liturgical movement, opening with recognition of the broken world and our own brokenness, and proceeding at the conclusion toward an affirmation of the eucharistic act. It is a tidy device, evidence of long experience in that deliberative space. Good homilies move in the present, whatever they may memorialise or foreshadow. There are things here the reader will return to.

W.H. Auden enjoyed quoting this Jamaican riddle: ‘And smart as little Tommie be, one man kill the whole world – Mr Debt.’ Despite the abundant praise of life and place and person, even because of it, this book has a certain elegiac air. Its existence is a reminder that seventy is a good biblical number. But repeatedly, sometimes extravagantly, Steele is trying to show in this book what can be done in a short space. Jonathan Swift, another of his near-idols, held the view that all people are either fools or knaves. Swift felt it important that he be remembered as a fool, not a knave, and it must be observed how often in Steele’s poetry and homilies he turns good-humouredly, perhaps wisely, to forms of human folly. In the opening poem, he even seems to identify directly with ‘the christian fool … charged as ever / with making out the vestiges of glory’. This is a self-reckoning at some fair distance from the knavish world leaders of his infancy.

Comments powered by CComment