- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letters

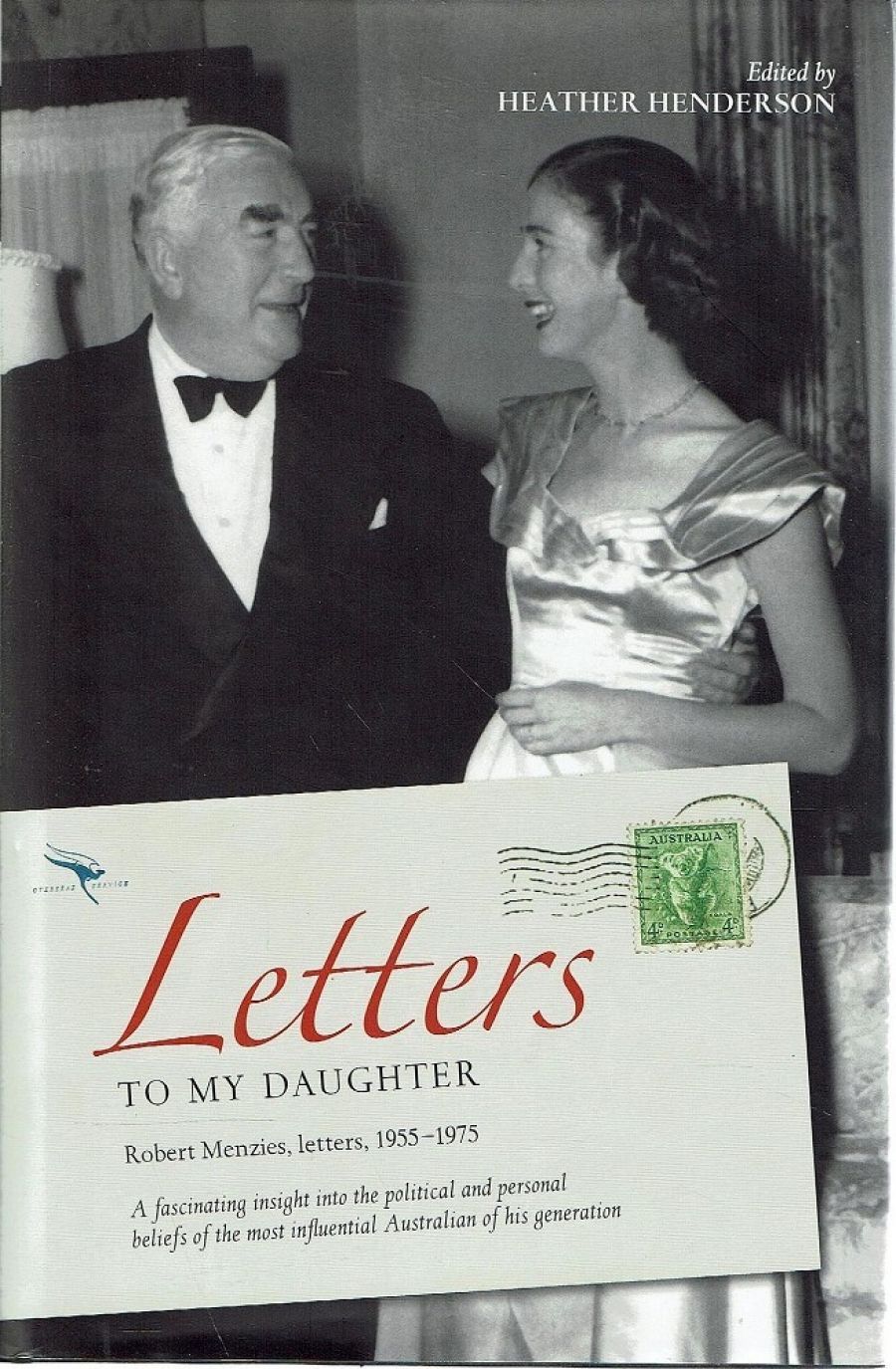

- Custom Article Title: Sue Ebury reviews 'Letters to My Daughter: Robert Menzies, Letters, 1955–1975' edited by Heather Henderson

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Heather Menzies was ‘the apple of her father’s eye’, reported A.W. Martin, Sir Robert’s authorised biographer, and this collection of letters reveals that she was indeed, to use her father’s own words, ‘the great unalloyed joy of my life’. So much so that Ken, her elder brother, confessed to being jealous of her in his younger days. Heather married Australian diplomat Peter Henderson in 1955 and moved to Jakarta, when these letters begin, but her political education began years beforehand. In a letter that Menzies wrote to Ken (not published here), who was serving in the Australian forces during the war, he proudly describes his sixteen-year-old daughter’s ‘sotto voce comments in the galleries during speeches by such favourites as Forde and Ward and Evatt … [as] worth going a long way to hear’. This extremely close relationship and sharing of political values between father and daughter had an interesting precedent: Dame Pattie had enjoyed a similar bond with her father, the politician and manufacturer John William Leckie. Politics was the stuff of life for the Menzies family, both in Opposition and government. Heather accompanied her parents on official engagements that included overseas trips to India in 1951 and London in 1952, and travelled with them on the hustings during electoral campaigns.

- Book 1 Title: Letters to My Daughter: Robert Menzies, Letters, 1955–1975

- Book 1 Biblio: Pier 9, $39.99 hb, 296 pp, 9781742662497

In 1949, when the Liberal–Country Party Coalition won government, Menzies became prime minister and led his party through seven electoral victories over eighteen years until he resigned of his own accord in 1966. He began discussing his retirement from politics with Heather before the cliff-hanging election of 1961, and by January 1962 he confessed that he was ‘depressed … all my plans for a decent retirement, leaving a … majority to carry on, seem to have gone’, given their one-seat majority after appointing the Speaker. Added to which, Billy Wentworth and Wilfrid Kent Hughes were ‘making mischief’, and Harold Holt and ‘problem child’ John McEwen entertained ambitions for the leadership, ‘a trouble which I must get off my chest to you since I cannot do it elsewhere’. Relaxation at the cricket, which Heather also enjoyed but which bored Dame Pattie, always granted relief from these concerns.

The letters, divided into five sections and powerfully evoking for his absent daughter the sound of her father’s voice, were dictated to his personal secretary, Hazel Craig, and arrived by diplomatic bag in Jakarta, Geneva, London, and Manila. After his retirement, Menzies accepted an invitation from the University of Virginia to become a Scholar in Residence, and the fifth tranche covers the four months he spent in Charlottesville. Less intimate than the letters to Heather, because they were generally round robins sent to the entire family, they are nonetheless frank accounts of life in the United States, on campus and on the lecture circuit. But it is in his sardonic observations about John Gorton’s unsuitability as leader of the Liberal Party and his twenty-something Principal Private Secretary Ainslie Gotto; the engagement and marriage of the ‘sorrowing widow’ Zara Holt to Jeff Bate; the state of the Liberal Party (which by now Menzies believed was a ‘leaderless rabble’); and ‘that untrustworthy little scamp McMahon’ that we recognise the eloquent, ironic, often caustic voice of Robert Menzies, who could reduce to impotence his opponents on the floor of the House – and in the process enjoy ‘giving them a good walloping … I felt five years younger when I had done the job’.

Private letters and diaries are eagerly sought by biographers; they yield insights into character and motivation that are available in no other documents, and Letters to My Daughter exposes a more rounded and sympathetic view of Menzies than we have enjoyed hitherto. His sense of family was strong, and his deep pleasure in his grandchildren palpable – there is a telling passage following the 1961 election when he confesses that he would sooner sit in Heather’s house in Geneva ‘and have my trousers dampened by my latest grandchild than travel around Australia on a general election campaign’. Menzies airs his dislike of the press, particularly the Sydney Morning Herald and the ABC, but the media were less intrusive in those days and he was able to retain a private life. Sir John Bunting, who was closely associated with him for many years, recognised that his prime minister’s friendships were ‘in separate compartments’ and there were no ‘friendships … on whom he was dependent, and with whom he might share his confidences or troubles’. We can speculate that he shared his problems with his wife, and we know now that his daughter was his close confidante.

Henderson confessed in her ABC interview that ‘some of it’s not in the book’. What has been omitted, and will we ever know? Since there are no ellipses in the letters, the locations of the ‘few excisions’ she made are concealed; and, apart from the occasional pompous comment and a naïve delight in the royal family, the reported instances that one has come to expect of Menzies’ arrogance, his excoriating wit, and oversentimental remarks about England do not appear – nor his apparent gift for mimicry and his comic sense – although there is a sly dig at a couple of society matrons in an account of ‘Snobbery Considered as a Fine Art’, when Lady (Hannah) Lloyd Jones and Elsie Dennett ‘with the fierce eyes of rivalry dredg[ed] up their memories of all titled people they have ever met … referring to them as “Tom” or “Mary” … a magnificent encounter’. The book abounds in political discourse. Of particular interest are his highly critical views of the Liberal Party in Opposition following the victory of the Labor Party in 1972, when ‘the party which I created, a party which had principles to which I most firmly adhere [and] which have now been completely abandoned by what they call little “l” Liberals’ reduced him to despair.

Access to the Menzies family’s private papers has rarely been given: Allan Martin’s intense scrutiny of the political career overwhelms his investigation of the private man, even though he referred to the letters and diaries for the two-volume biography (1993 and 1999), and Judith Brett lacks this privilege for Robert Menzies’ Forgotten People (1992). Manning Clark used the official papers in the National Library of Australia for his poisonous portrait of Menzies in A History of Australia, and, although he recanted to his publishers after time spent discussing the issues with Martin, it was too late to change his published conclusions. These letters are valuable, therefore, to political scholars and historians (although the lack of an index is irritating), for they possess the immediacy of recently dictated correspondence: no fair copies or later revisions. They also track the decline from robust health to old age of a major Australian political figure.

Loved, hated, revered by many, reviled by others, ruthless to his opponents, magnificent in debate, he captured the votes of women and the Australian middle class that swept him to power in 1949, and the phrase from his radio broadcast to Australia’s ‘forgotten people’ resonates still. One question remains. His sister Isobel suggested that he would have liked the letters to be published, so did he write them with an eye to posterity? His daughter believes that they were written ‘simply for me’ and not for ‘public edification’, and so do I, but readers must make up their own minds.

Comments powered by CComment