- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

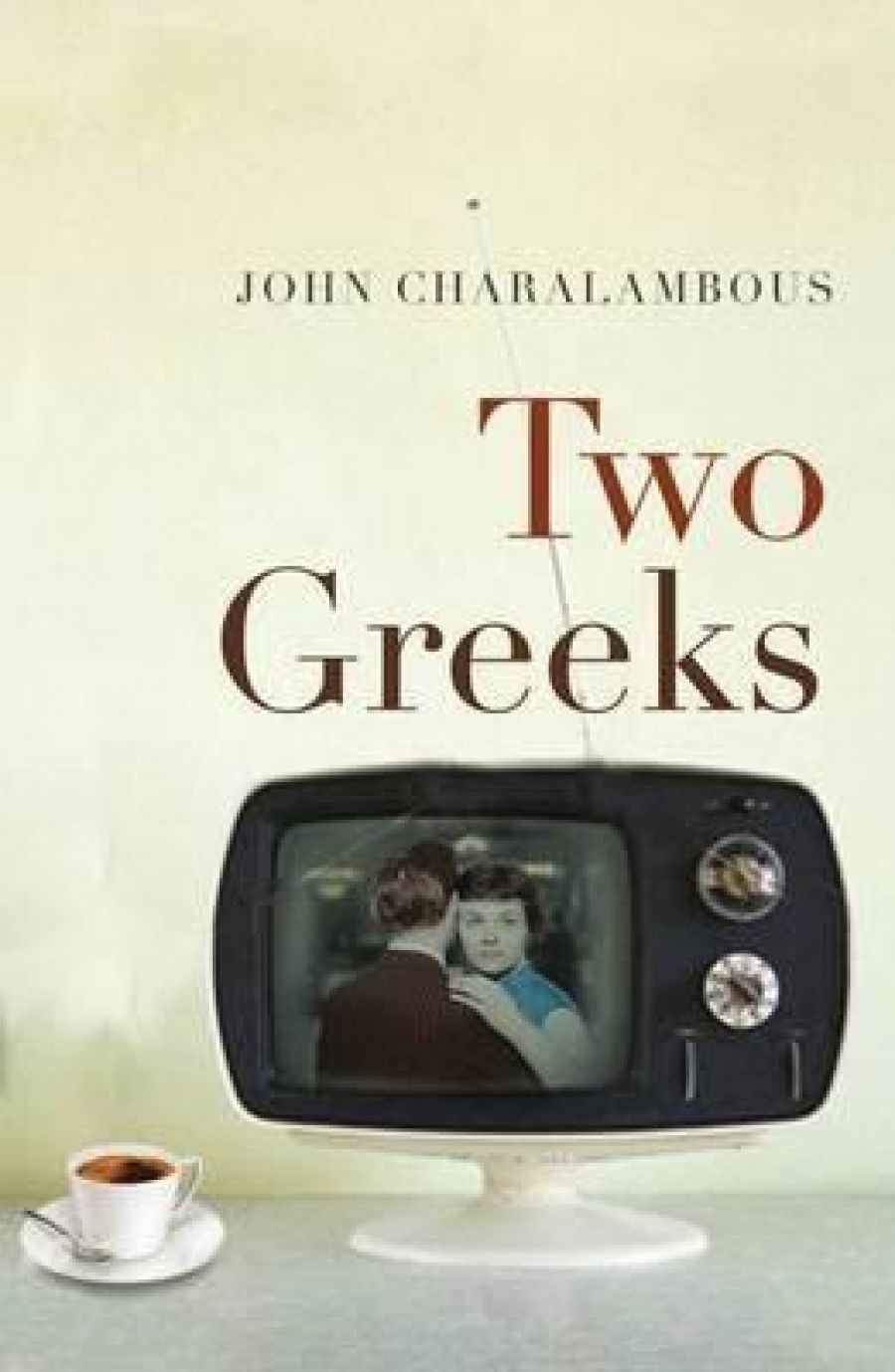

What does a young boy make of a father who carries in his pocket a knife that is used to peel fruit, behead chickens, fashion toy flutes, and potentially serves as a weapon to kill his spouse? Two Greeks,the work of third-time novelist John Charalambous, is an engaging study of the power of family and the need for identity. In similar company to Raimond Gaita’s Romulus, My Father and Christos Tsiolkas’s The Slap, the novel delves into difficult emotional territory, but does so with humour and humanity. Like its literary cousins, it has the foundations for an insightful filmic adaptation.

- Book 1 Title: Two Greeks

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $24.95 pb, 264 pp

Ten-year-old Andy is the narrator of this tale, which strives to give his mother, Carol, a voice. Carol becomes the imagined reader of this shared history, which recounts one tumultuous year, 1974, when their family is disintegrating. While the book is a tribute to his mother’s resilience, it is also an attempt to tell his father’s sorry story. Harambalous Stylianou, also known as Harry, is the tyrannical ruler of this suburban family. Andy’s recollections work not to justify his father’s abhorrent behaviour, but to put them into the context of the pain that emerges from a history of poverty, isolation, migration, and lost opportunities.

Harry detaches himself from his Greek colleagues at work, derides all that comes from his own Cypriot heritage, leaves Brunswick, and settles incongruously in the bayside suburb of Hampton, ‘where he was the only Greek in the street, perhaps the only foreigner’. Harry distances himself further from his origins by marrying a non-Greek, a choice with the potential to create a new cultural dynamic. But a man cannot run from who he is or the personal history that has shaped his outlook. ‘Harry’s anger is a brute phenomenom, unpredictable, unreasonable, untraceable in its origins, surging with forces unleashed in unseen altitudes, in other times.’ Harry’s moodiness sets the tone each day. In this state, Carol tries to keep the peace but also carries years of resentment; Andy is fearful, bemused, hopeful; while his fourteen-year-old sister, Angela, is combative and aggressive towards her father.

Andy’s good-natured mother is full of ‘wishes’ that her husband might have been a different person had his life worked out otherwise. Andy recounts that Harry ‘certainly picked his mark in choosing to approach you, a timid fat woman … you married the first man to show concerted interest’. Early in their marriage, Harry’s jealousy, his control of the family finances, his roving hands and demanding sexual needs, his bullying, and general tyrannical behaviour exhaust Carol emotionally. She feels physically spent, gains more weight, and admits herself into a psychiatric hospital after the birth of each child, fearing the loss of her sanity and desperate for rest. By 1974 Carol is in a holding pattern, aware that no-fault divorce legislation is an imminent possibility and one that would not compromise the safety or health of her children.

The second Greek of the novel’s title is introduced in a scene when Harry is raging at the gods, throwing lemons into the air in his backyard, insulted that his efforts to mow the lawn have been curtailed by heavy rain. ‘He erupts into a sibilant tirade of wog-talk – ugly words that scour his throat, dirty filthy words, infinitely more dirty and filthy for being unintelligible.’ A bodiless voice from over the fence speaks courteously and with authority in Greek leaving Harry uncharacteristically speechless. We never learn what is said, but it’s enough to alter Harry’s behaviour and to change the course of this family’s engagement with each other for the ensuing year.

Andy engages with their new neighbour, the ill and elderly Alex Voreadis, when he is offered one dollar a day to walk Alex’s dog, a recalcitrant creature more often than not carried by Andy, who feels empowered by his new earning capacity. He imagines the record player he will buy, the gifts for his family, and the bonhomie this will generate. Andy’s Greek neighbour becomes an intimate companion, sharing his life story, political views, and religious beliefs. He teaches the young boy Greek, shows him trust and respect. In Alex, Andy not only finds a friend and surrogate father, but also gets closer to understanding his own heritage.

The two Greeks meet in person only once, a neighbourly interlude behind closed doors, to which no other family member is privy. We imagine that it is the Turkish invasion of Cyprus that brings them together, but there is an underlying mysteriousness to the story that keeps the reader guessing about the exchange between the two men.

Charalambous creates complex, contradictory characters in constant battle with their dreams, their reality, and their profound limitations. Ten-year-old Andy’s perspective is heartbreaking yet life-affirming, engendering in us a tenderness about what it is to be young and in search of role models. Two Greeks, a welcome tale in the Australian literary landscape, penetrates the often-clichéd territory that is southern European migrant culture.

Comments powered by CComment