- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

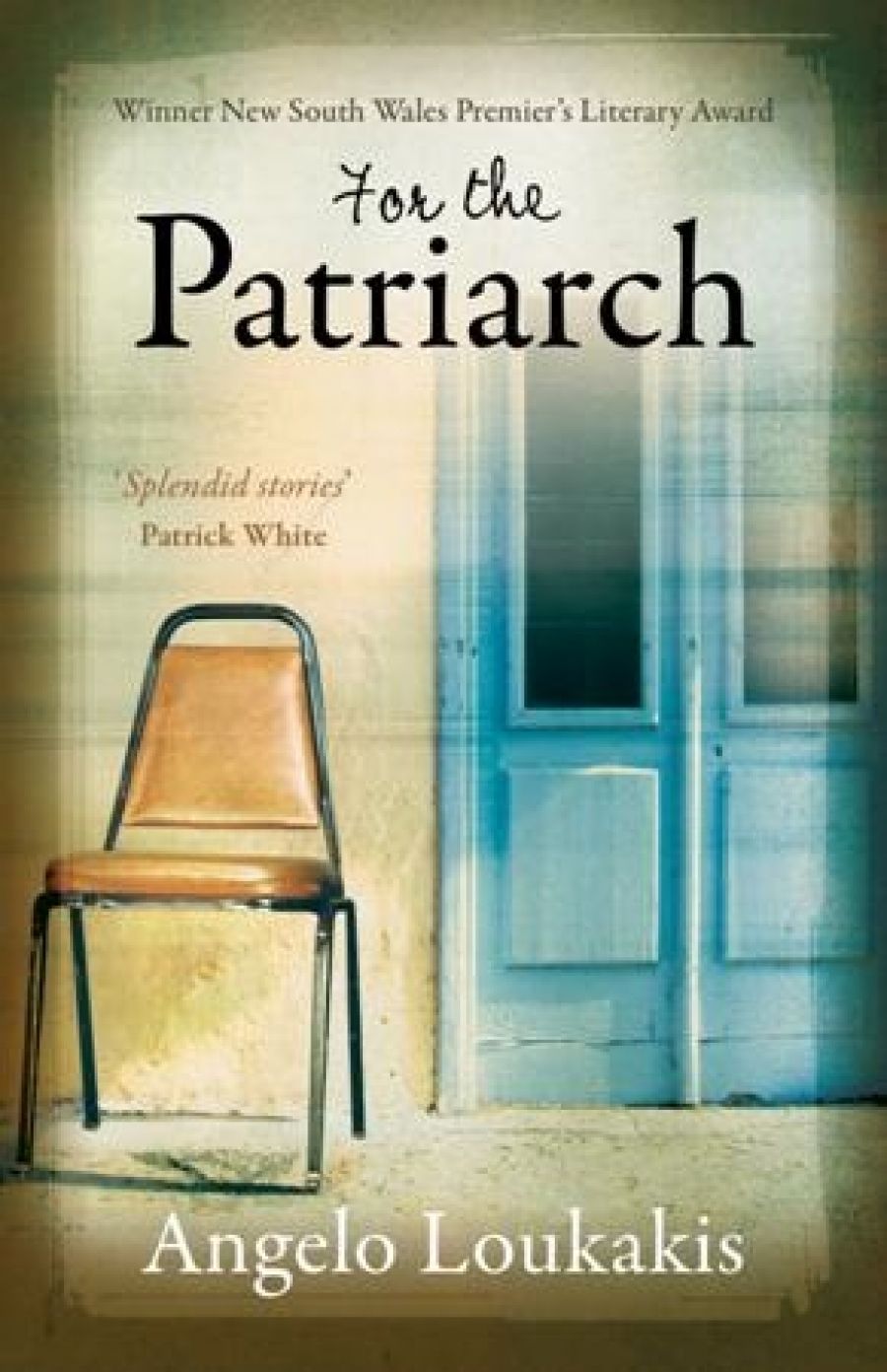

For the Patriarch first appeared in 1981 and was much lauded, winning a New South Wales Premier’s Literary Award. The work is an important landmark in migrant writing. Angelo Loukakis, although born in Australia, identifies with the first generation of post-World War II migrants who are under-represented in our literature. Their children and grandchildren are the ones who have engaged with the complexities of what it means to be Australian while acknowledging that their roots lie elsewhere.

- Book 1 Title: For the Patriarch

- Book 1 Biblio: Krinos Press, $24.95 pb, 192 pp, 9780868064659

Revisiting these stories, I was interested to see how they had worn. There is a new sense of urgency about preserving anything pertinent to that great wave of people who came to Australia from Europe in the 1950s. If we want to catch their voices, we must do so before it is too late.

Identity is the eternal and ultimately unanswerable conundrum of what it means to be a migrant. Not surprisingly, the implications of relinquishing your original identity – the how, and if, of engaging with the dominant culture of the new country – lie at the heart of For the Patriarch. These dilemmas are most poignantly illustrated in the title story. Written as a series of letters from a dutiful son, a newly arrived Greek Orthodox priest communicates with his parents back home in their village. Or does he? We are not privy to the parents’ replies. The narrative drifts along an expected trajectory: Sydney is unexpectedly bigger than Athens, the queen of England is inexplicably the queen of Australia. The priest finds the ‘expatriate Greeks’ disheartened, and concludes that leaving their homeland ‘has hurt them very much’. They speak to him about money, work, and their businesses; and are not concerned about worshipping God. Australia is ‘a giant’s landscape and a desert not for humans’. The Greeks, for their part, view the young priest with suspicion. He becomes a physical and mental isolate, and immerses himself in reading a history of the Byzantines.

In a marked shift, Loukakis alters the story’s course with this line: ‘As you know well enough we Greeks belong to the Empire.’ The Byzantine empire of a thousand years ago, that is. The young priest’s journey ends in delusion, without his ever engaging with his new country.

Going back to see for yourself where you or your parents came from is a predestined journey for the migrant. If you identify yourself within your original culture, there is additional complexity. In ‘Lassithi’, the narrator, like Loukakis, traces his ancestry to Crete, adding another layer to the labyrinth of what it means to call yourself Greek – and Greek Australian. The narrator, Aris, says, ‘I speak this language at times as if it were my only one. And yet so long ago my parents had packed their bags and left ... Now I am a tourist.’ Aris encounters a man who is even more estranged from his identity. This man is searching for Aris – not narrator Aris, but another one. Or maybe the narrator after all.

The Australianised boys in ‘Dancing’ don’t want to be Greek, despite being told by their parents that is the essence of their identities. They don’t want their girls to look ‘too Greek either, y’know?’ At a dance where their elders are dancing to mandolins and bouzoukia, the boys are told by one of a party of girls, ‘And you can all get nicked.’ The girls are Greek; Australianised like the boys. But this is equivocal; they might at any moment revile the boys in fluent Greek.

The boys who would be men leave the dance full of impotent bravado. They could go to a pub, yet end up in a milk bar run by a Greek listening to American music, the same sort of place where their evening began. They are caught between boyhood and manhood, between being Greek and wanting to be Australian with ‘normal’ names like ‘Bill’. Adulthood, we sense, will sort out some of these concerns and will also entrench their confusion about identity.

The notion of place is profound in these stories. The inner suburbs of Petersham and Marrickville are sensitively rendered as a Greek migrant locus, a battlefield between the generations. The strangeness of Sydney is conjured up with imagery of botanic gardens that are ‘better than the King’s Gardens’ back home in Athens. In ‘Friends’, a visit to a surf beach on the south coast of New South Wales becomes a meditation on Cavafy and on taking male friendship to another level; a possibility of time, place, golden youth for the ‘other’, the migrant; an impossibility for the friend, an Australian boy who has never even heard of the Bosporus. Place thus anchors the narrative and is the unsettling agent.

The switch to another culture, another language, is the most remarkable thing that most of the characters in these stories will ever achieve. That effort of will seems to exhaust them. Their children and grandchildren are the ones who have to make sense of it all.

Immigration to Australia continues; the originating countries change, that’s all. The overarching theme of self-identity, what it means to accommodate yourself to another culture, is a constant. These exquisite stories from a master practitioner who first explored these concerns thirty years ago are as relevant now as they were then. They reward rereading.

Comments powered by CComment