- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: International Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Tariq Ali, proclaims the Guardian, ‘has been a leading figure of the international left since the 60s’. If his latest book is the best the left can muster, I fear that its chances of influencing political debate are minimal – and, even worse, undesirable.

- Book 1 Title: The Obama Syndrome

- Book 1 Subtitle: Surrender at Home, War Abroad

- Book 1 Biblio: Verso, $29.95 pb, 219 pp

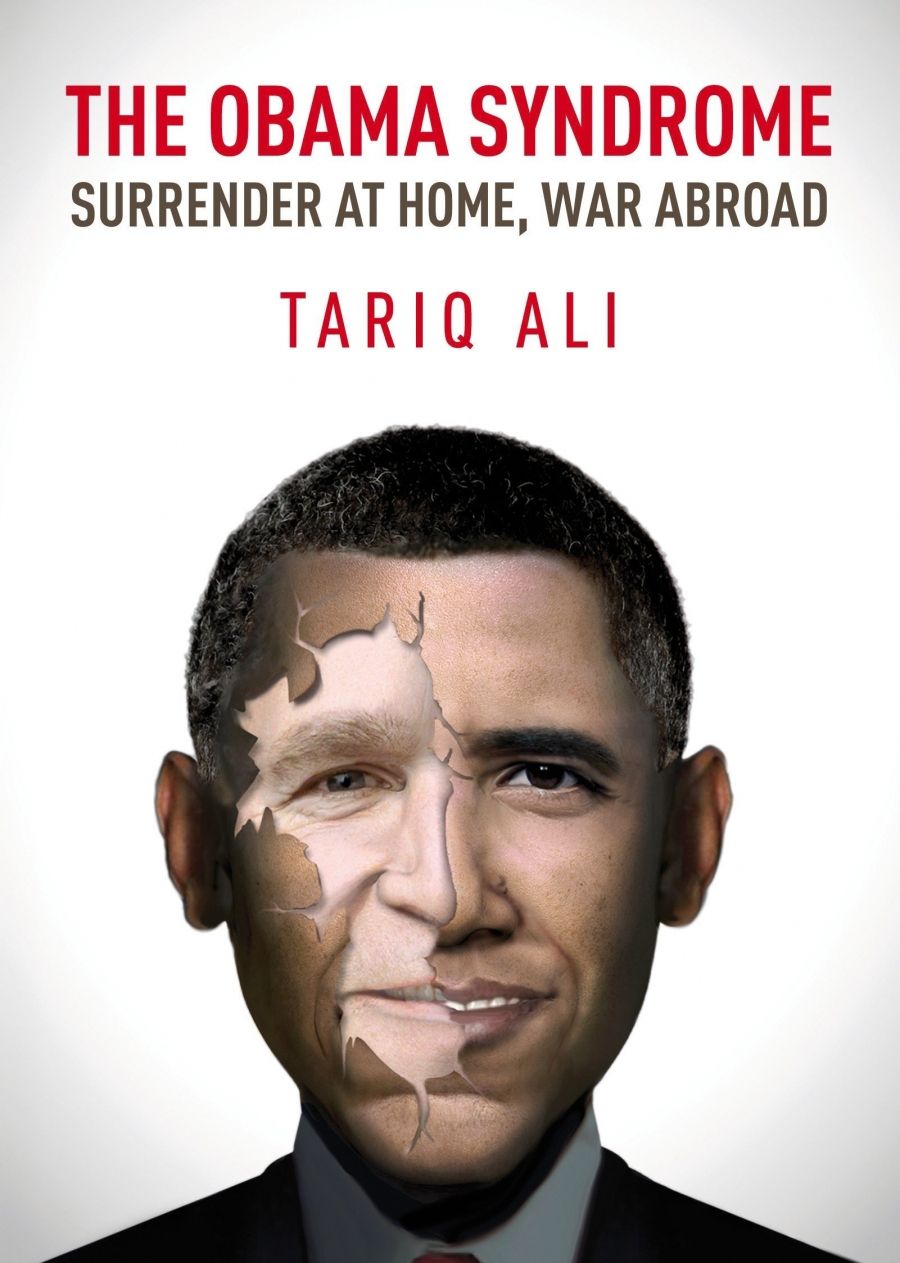

The cover of The Obama Syndrome depicts four images of the president in which his face gradually whitens in a way reminiscent of Michael Jackson. The subtext is clear: Barack Obama has betrayed his racial origins by not being more radical. (One of Ali’s sources is former Illinois state senatorial colleague, Rickey Hendon, who wrote a book on Obama called Black Enough White Enough: The Obama Dilemma [2009].)

It is ironic that a left-wing author and publisher are so willing to echo the covert racism of Obama’s opponents who argued that an African-American would not sufficiently understand American values to be a good president. Perhaps this is explained by Ali’s nostalgia for the Black Panthers, whom he eulogises as genuine radicals whose legacy Obama has betrayed. That nostalgia extends to a hyperbolic style of writing. While Obama is consistently denounced, protest against the recent attack by Wisconsin’s Governor on public sector unions is seen as ‘an unexpected eruption of class struggle … inspired by the Cairo protests’. Both of these assertions might rather surprise the government employees of Duluth and Oshkosh who were demonstrating for their job security, but Ali does acknowledge that they lacked a coherent political strategy.

There are real and serious questions to be asked about the social, economic, and political health of the United States, and Ali is correct to link them to the apparent failures of an unconstrained free market to deliver basic needs to large numbers of its citizens. The American system is beset by striking failures, including the large numbers of homeless, of people denied basic health care, or the growing inequality that is squeezing millions of people out of a decent existence. At the same time, its politics are increasingly polarised, with the possibility of a powerful right wing, inspired by ideological and religious fundamentalism, winning control of both the White House and Congress next year. All this, it would seem from Ali’s book, is largely due to the failures of President Obama, who has proven to be yet another synthetic politician unable to accomplish meaningful reform:

Obama has become the master of the sympathetic gesture, the understanding smile, the pained but friendly expression that always appeared to say: ‘Really, I agree and wish we could, but we can’t …’ The implication is always that the Washington system prevents any change that he could believe in.

Ali wrote much of this book before the 2010 mid-term elections, and before the recent battles over US debt levels showed just how crucial was the loss of Democratic control of the House of Representatives. Yes, Obama could have been tougher, and like many of his critics I wish he had not compromised about the removal of tax avoidance schemes for the rich. This is a common criticism of Obama: in a recent New Yorker,Hendrik Hertzberg wrote of his ‘all too civilised, all too accommodating negotiating strategy’ (‘Talk of the Town’, 8 August 2011).

But even if Obama had dug in and forced a showdown with the Congress, this leaves unanswered the great dilemma for American progressives, which is that over the past few decades the electorate has consistently turned against the mildly redistributionist policies of the New Deal and Great Society, while supporting social welfare provisions such as Medicaid. Despite the Global Financial Crisis, the left has failed to create a meaningful alternative to the ‘third way’ politics of leaders such as Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, and the financiers who caused huge financial institutions to collapse are now firmly in control of the system that they demonstrably rorted.

Ali points to the economic advisers brought into the Obama administration, most of whom were integral to the earlier deregulation of the economy that helped create the crisis they now sought to resolve. At one point, he laments that Obama’s policies were less radical than Richard Nixon’s. But this is an ahistorical comparison, which fails to recognise the extent to which the larger ideological climate has shifted.

As Fareed Zakaria pointed out recently, Obama ‘is a pragmatist who understands that in a country divided over core issues, you cannot make the best the enemy of the good’ (Time, 22 August 2011). I too wish that Obama could push the country closer to the radical vision he seemed to suggest in his pre-presidential writings. But it is too easy to simply blame Obama for the larger institutional and ideological framework within which he operates.

Predictably Ali is scathing about Obama’s foreign policies, which he sees as a continuation of Bush’s attempt to impose American influence throughout the world in the interests of the military-industrial complex. I suspect his views of the Afghanistan adventure are more correct than those of the administration, but I am less persuaded that there is no altruism in the mix of motives that has created the current quagmire. This section is the strongest part of the book, and Ali is right to point to the reality that Obama has altered the rhetoric more than the substance of United States foreign policy. He finished this book before the NATO intervention in Libya, which he condemned, predicting the failure of the uprising.

The Obama Syndrome is a symptom of the British left’s desire to demonise the United States, which leads to analysis more like a prosecutor building a case than an analyst seeking to understand complexities. It reminded me of the two remarkable novels by James Miller – Lost Boys (2008)and Sunshine State (2010) – both of which begin brilliantly but are let down by a heavy-handedness in their treatment of American imperialism.

The tone of Ali’s writing echoes the strident certainties of the right, neither prepared to give ground as they talk past each other. At times this verges on the offensive, as in his dismissal of Richard Goldstone, who chaired the United Nations investigations into Israel’s incursions into Gaza last year, as ‘one of the most notorious time-servers of “international justice” … a self-professed Zionist’. Given the ferocity of the attacks on Goldstone from within the Jewish community – in South Africa his congregation prevented him from attending his grandson’s bar mitzvah – this is tacky indeed.

Equally, the only mention of homosexuality in the book is a snide remark about J. Edgar Hoover as ‘a closet homosexual’, which even Ali realises might be going too far, as he excuses this with a long footnote explaining that he and the now dead film director Derek Jarman joked about it. Jarman was openly gay, a point we are supposed to deduce because, as Ali tells us, he died of AIDS. Hidden in a footnote on page one hundred is the remarkable claim that in Cuba: ‘Sustained research on HIV/AIDS has produced an effective vaccine now being made available to the poor countries around the globe.’ Unfortunately, no such vaccine exists. Tariq Ali’s future publishers would be well advised to employ a fact checker.

Comments powered by CComment