- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

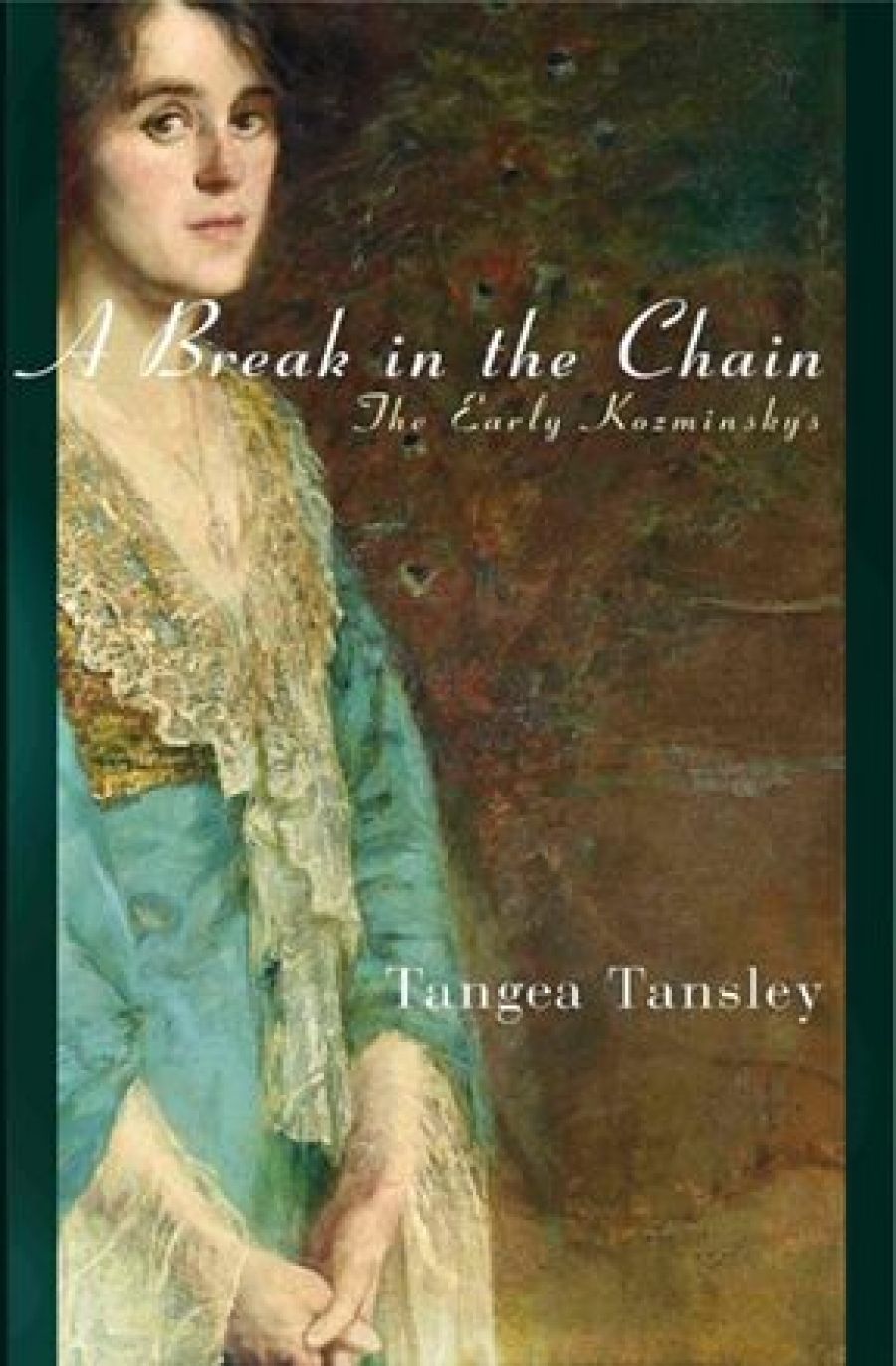

- Custom Article Title: Miriam Zolin reviews 'A Break in the Chain' by Tangea Tansley

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: A Break in the Chain: The Early Kozminskys

- Book 1 Biblio: Affirm Press, $27.95 pb, 320 pp, 9780980790467

At the beginning of the book, Simon Kosmanske is evicted by a stern father from the family hearth in what was then Prussia. After a hellish sea voyage he lands in Western Australia, but the only opportunity on offer there is whaling and he can’t bear the thought of all that killing, so he heads east – to the young town of Melbourne and the gold rush at Ballarat. At home, before his adventure begins, he is a soft-hearted and unambitious young man, lusting after a local village girl and sitting under a tree playing the fiddle to his father’s herd of milking cows, whose velvet hides he caresses for comfort.

On arriving in the colony, Simon purchases a horse, establishes a carting business, lives in Ballarat, Mortlake, and Melbourne, marries the inscrutable Emma, and starts a family. His first-born – Israel – becomes the central character for the rest of the story. Even though the first third of the book is Simon’s, we don’t really get a sense of him. Those early times in the colony must have been tumultuous, yet any sense of tumult is strangely absent.

For much of the first part of A Break in the Chain, Simon seems disengaged. Leaving aside the troubled and largely unexplored relationship with his father, we find that a shipboard friendship with Jack (the insufficiently persuasive whaler), multiple encounters with the con artist urchin Ted, and even his interaction with Emma and later his sons paint a picture of a man incapable of forming real, human attachments. The most emotion we see is when he falls to the ground distraught as his horse collapses and dies in the street. Is he only capable of tenderness towards animals? As the novel unfolds, however, a doubt starts to form in the mind of the reader. Is Simon’s disengagement the author’s clever way of revealing a flawed character, or are we simply reading flawed writing?

The suspicion grows as the book’s focus shifts to Simon’s son Israel, who changes his name to Isidore in response to schoolyard anti-Semitic bullying. Thirty-five years of Isidore’s story are documented through the main section of the book. We see him struggle in his relationship with the Jewish faith, with his father, with his mother. We see him trying to find his place in the world. We are moved anecdote by anecdote through the larger narrative. Character arcs are missing. Story lines are started and dropped. We glimpse a novel underneath, tantalising. We never quite touch it.

Feeding the growing sense that the writing does not do justice to the intriguing fictional potential, anachronistic word usage and observations may unsettle not only the linguistics nerd and the history buff, but also those readers who will wonder in passing if it is appropriate for someone in 1858 to be saying of a horse that ‘Being shod freaks her out …’ The first documented use of ‘freak out’ in this sense was in 1966. Other words are also used out of their time. ‘Posh’ was not in regular use as it appears here until around 1918. ‘Vibes’ did not mean ‘energy vibrations’ until the late 1960s. There are more. Add incongruities such as a reference by Simon in the 1890s to early closing in pubs (instituted in 1916) and a number of adult characters in the 1800s referring to each other by first name in public, and you start to feel uneasy; not in safe hands. There is no rule that says a book written about another time should be true to the voice and tone of that time, but a seemingly careless use of a twenty-first-century sensibility interferes with our ability to engage with the times and be immersed in the story.

As a family history, the book is compelling. Fascinating individuals and complex relationships characterise the family behind the Kozminsky jewellery shop now located in Bourke Street, Melbourne. In the book’s postscript, Tangea Tansley reveals that her first choice for a central character was Emma, Simon’s bride and the mother of Israel/Isidore/Francis. However, researching this enigmatic woman led to sufficient dead ends to force a tough decision to leave Emma, barely revealed, in the shadows.

The postscript is also a useful aid to understanding and excusing the book’s weaknesses. It provides insights into the factual gaps that Ms Tansley had to navigate, and into the extent to which the Kosminsky family provided encouragement and assistance. The tale might have benefited from a more objective author; one less constrained by respect, more inclined to craft engaging fiction for its own sake.

The novel and family history are necessarily different types of writing. In attempting to write one, it appears that Tansley has instead become deliciously and successfully entangled in the expectations of the other.

Comments powered by CComment