- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Reserve and pity almost meet in Andrew Marvell

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1629, Charles I of England sent Daniel Nys to Europe to buy art. Along with works by Titian and Rubens, Nys bought Mantegna’s masterpiece, The Triumphs of Caesar (1486–92). This work on nine large panels is at once sombre and full of wonders. Of its time the most accurate representation of Roman customs and costumes, it is also a work in which precision has a strange effect, almost of tenderness. Still hung at Hampton Court, it was one of only a few works that Cromwell kept after the regicide.

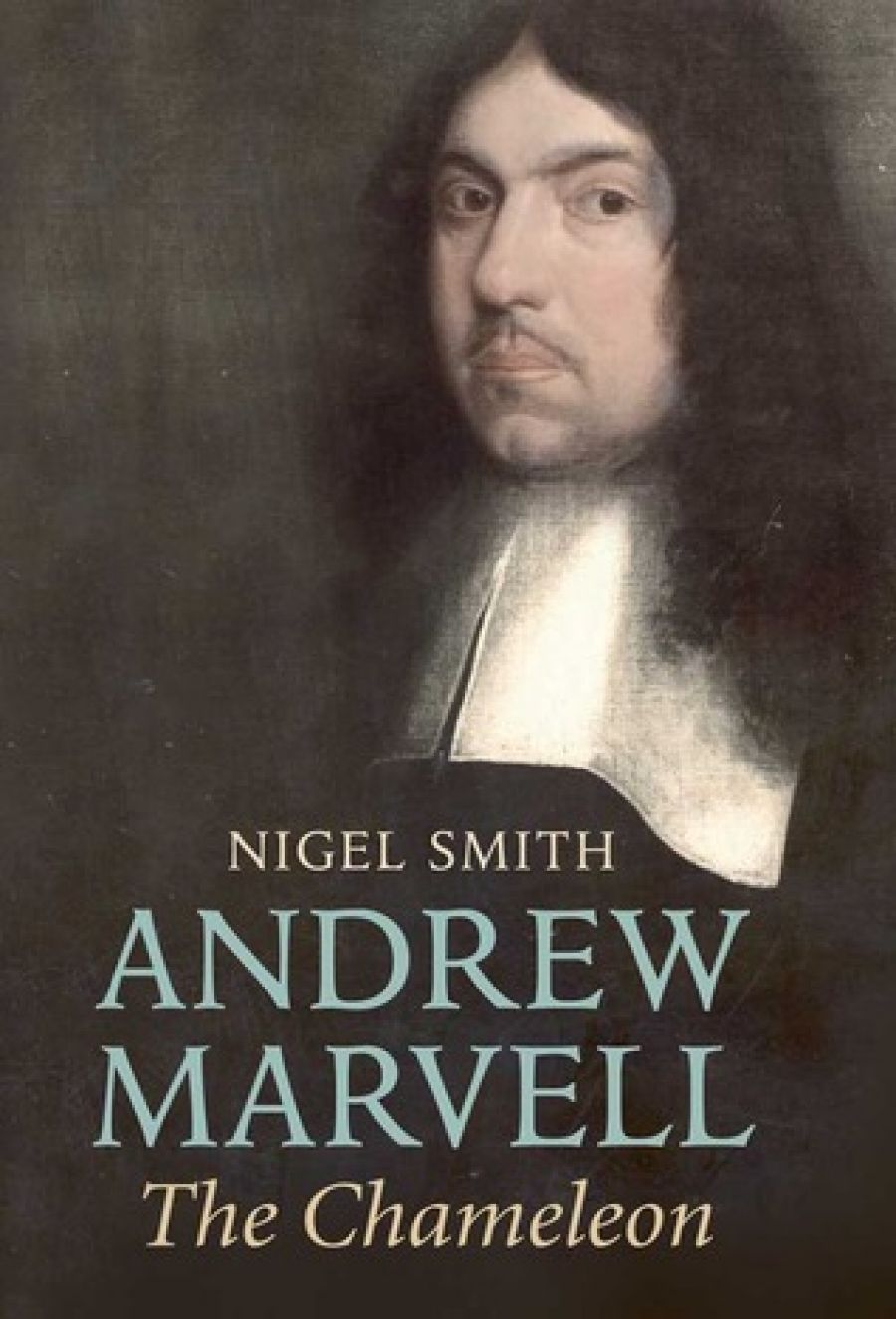

- Book 1 Title: Andrew Marvell

- Book 1 Subtitle: The chameleon

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press, $55.95 hb, 416 pp

This painting, exact and strange, holds the mood of Andrew Marvell’s poem ‘An Horatian Ode upon Cromwell’s Return from Ireland’. The resemblance is not simply a matter of imagery. It was the fashion of that time to discuss contemporary politics in terms of Caesar. On one level, Marvell was writing conventionally in describing Cromwell: ‘Then burning through the air he went, / And palaces and temples rent: / And Caesar’s head at last / Did through his laurels blast.’

The resemblance is more a matter of mood. Like Mantegna’s painting, Marvell’s ‘Ode’ casts what it sees in a bare light, with an effect less of realism than of some curiously lucid dream. This bare light could perhaps be called the light of history, which shows events at once clarified and opened out into long perspectives. It is in this light that Marvell assesses Cromwell: ‘And, if we would speak true, / Much to the man is due, / Who, from his private gardens, where / He lived reserved and austere, / As if his highest plot / To plant the bergamot, / Could by industrious valour climb / To ruin the great work of time …’

Marvell is a poet whose interest derives very much from his peculiarity of tone. Sometimes characterised as ironic, it might better be characterised as a tone in which reserve and pity almost meet. Marvell’s ‘Ode’ was first taken up by the Royalists. Later, they took it to be a panegyric of Cromwell; critics still argue over which ‘side’ Marvell takes in this poem. Yet it is a poem that makes talk of ‘sides’ seem beside the point. In ‘the great work of time’, one cannot but be on the side of the present.

The tone of Marvell’s poetry – its combination of tenderness and detachment – works alongside those tricks of scale, which characterise the work of Marvell as much as Mantegna. Marvell creates jewel-like images and phrases, which often seem greater than their settings. In this way, he sets up a curious play of perspective: reading, we seem to see things at once close up, and from a great distance – the closeness a matter of heightened perception, the distance as much of time as of space. In ‘Bermudas’, for instance, the poem’s framing device is oddly perfunctory: ‘Where the remote Bermudas ride / In the ocean’s bosom unespied, / From a small boat, that rowed along, / The listening winds received this song.’ In this poem, the image of oranges ‘Like golden lamps in a green night’ lights up far beyond its frame. Marvell is a poet who seems always to be marking the end of something; which is to say there is, in his most caustic and fastidious of poems, a sense of yearning.

Marvell’s prose first made his name. His collected poems came out in 1681, three years after his death. For his contemporaries – and for the next two centuries – he was best known as a satirist, and as the author of An Account of the Growth of Popery. Yet, from the turn of the twentieth century, and prompted in part by T.S. Eliot’s Oxford lectures, Marvell became known, foremost, as a poet – as the author of ‘To His Coy Mistress’, which, if it is one of the most celebrated love poems in the language, is also perhaps the love poem least like a love poem, written as it is with a quizzical coolness: ‘the grave’s a fine and private place / But none, I think, do there embrace.’ As this might suggest, Marvell is a poet idiosyncratic and difficult to categorise: his poetry is surprisingly different from his prose; surprisingly different, also, from the poetry of his contemporaries, and even from the sort of poetry typically associated with the forms he chose to use.

However, in the past few decades, the fashion for ‘new historicism’ in literary studies has prompted an interest in Marvell’s poems and prose together. The American scholar Stephen Greenblatt established new historicism with his rightly celebrated book Renaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to Shakespeare (1980), which aimed to show how culture and politics shape the experience of inwardness. Nigel Smith, whose career as an academic was born under the star of new historicism, gained his first degree in history. Certainly, this biography of Marvell is better considered as a work of history than as a work of literary criticism, or literary imagination. Smith’s account of Marvell’s life is made of details, massed and wonderful. The result of tireless archival research, it shows Smith to be one of the leading experts on Marvell; it shows him also to be a part of the approach to literature that employs terms such as ‘leading expert’.

The biography has, as its great strength, this wealth of fact: where Marvell went, what work he did, what happened to the people whom he met. These details impose a sense of crowded daily work. In doing so, they illustrate how complicated statecraft was at that time; they show how large questions of religion, nationhood, and individual freedom worked their way into countless small decisions. Taken together, they justify that wariness which is, in portraits, the defining characteristic of Marvell’s expression.

Smith’s style is characterised by this accumulation of facts. His is not a mind to favour emblems: reading this biography brings no sudden illumination. Though rich in detail, it is not sensuous. It has not the texture of experience that several recent historians have worked to recreate: the sense of weather, for instance, in James Shapiro’s 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare (2005). That Smith’s biography works most cogently in its second part, where it follows Marvell’s public life, indicates its peculiar weakness and strength: it is chiefly concerned with Marvell’s public career. Under ‘Marvell, personality’, the index has just two page references; on his activities in parliamentary committee, it has thirteen; and this is not a failure of indexing. In that regard, this new biography appears to have that old motivation: working out, in exemplary detail, Marvell’s opinions; what ‘side’ he was on.

When it comes to Marvell’s poetry, this is too limited a question to be asking. Marvell’s best poetry relates in no simple way to the pressures of his time. It could be said that if, in his prose, Marvell defended the right to a private mind, in his poetry he marked out the place of it: the limits and possibilities of retreat. Even the ‘Horatian Ode’, perhaps Marvell’s most publicly committed great poem, draws public matters into a private question: it begins, ‘The forward youth that would appear / Must now forsake his Muses dear …’ It is characteristic of Marvell’s dryness that he opens a poem about his time by remarking that the time for writing poems has passed.

According to Smith, ‘much of that quality [of Marvell’s poetry] has to do with indecipherability, with irresolvable ambiguities, with seeing things all ways at once and yet never really revealing what the hidden author thinks’. For Smith, Marvell’s complexity of tone is only a form of prevarication, as though opinion were the final truth of experience. Smith takes an oddly bureaucratic approach to the writing, as well as the reading, of poetry:

After the city and its distractions, there would have been plenty of time to focus on literary gains of the last few years, and to assimilate them into his verse. There is no greater example of this than ‘Upon Appleton House’ itself and its construction. In it Marvell finally establishes his poetic identity and ruminates on his life’s achievements thus far.

Yet it would be hard to name a poet less likely to ‘ruminate’. Reading Marvell’s ‘The Second Chorus from Seneca’s Tragedy Thyestes’ alongside Cowley’s version emphasises how compressed Marvell’s writing is. His poetry is never confessional. If it establishes ‘poetic identity’ – if such a thing could be established – it does so only through its tone, complex and reserved, and by its strangeness: qualities which perhaps have least to do with ‘literary gains’ and ‘life’s achievements’.

Marvell’s repeated images – of green, of grass, of closed gardens, of insects, of flood – introduce a sudden magic into his poems. Perhaps, for this reserved and private man, these images introduce into the poems the recollected experience of writing poetry. With them, the poems, formal and lucid though they are, nevertheless open out into realms of mind, marvellous and strange: a trick of inwardness Marvell himself, with characteristic self-awareness, describes in ‘The Garden’: ‘Meanwhile the mind, from pleasure less, / Withdraws into its happiness: / The mind, that ocean where each kind / Does straight its own resemblance find / Yet it creates, transcending these / Far other worlds, and other seas …’

In his introduction, Smith defends the value of Marvell in terms least likely to reflect the value of his poetry:

For this reason, his life and his writing are worthy of anyone’s attention today: they address serious matters in today’s world of shifting values and encroachments on personal and civil liberty. The world is suffering the consequences of a financial crisis that has its origins, it is alleged, in the greed of those who operate the financial system; today, improperly equipped soldiers fall in battle on distant plains while politicians corruptly reap financial benefits from the taxpayer. Marvell would have understood all of these matters with innate wisdom, and his writings still address them.

As this might suggest, Nigel Smith’s biography reflects the public focus of an academic in a public-minded age, an age that struggles to define the value – the ‘relevance’ – of inwardness, and of style. This biography will be essential for any student of Marvell, yet it throws only occasional light on Marvell’s poems.

Comments powered by CComment