- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthology

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On 18 January 1773, less than twenty-four hours after first entering Antarctic waters and concerned by the ice gathering around the Resolution, Commander James Cook surveyed the waters. A few hours later he wrote in his journal: ‘From the mast head I could see nothing to the Southward but Ice, in the Whole extent from East to WSW without the least appearance of any partition.’

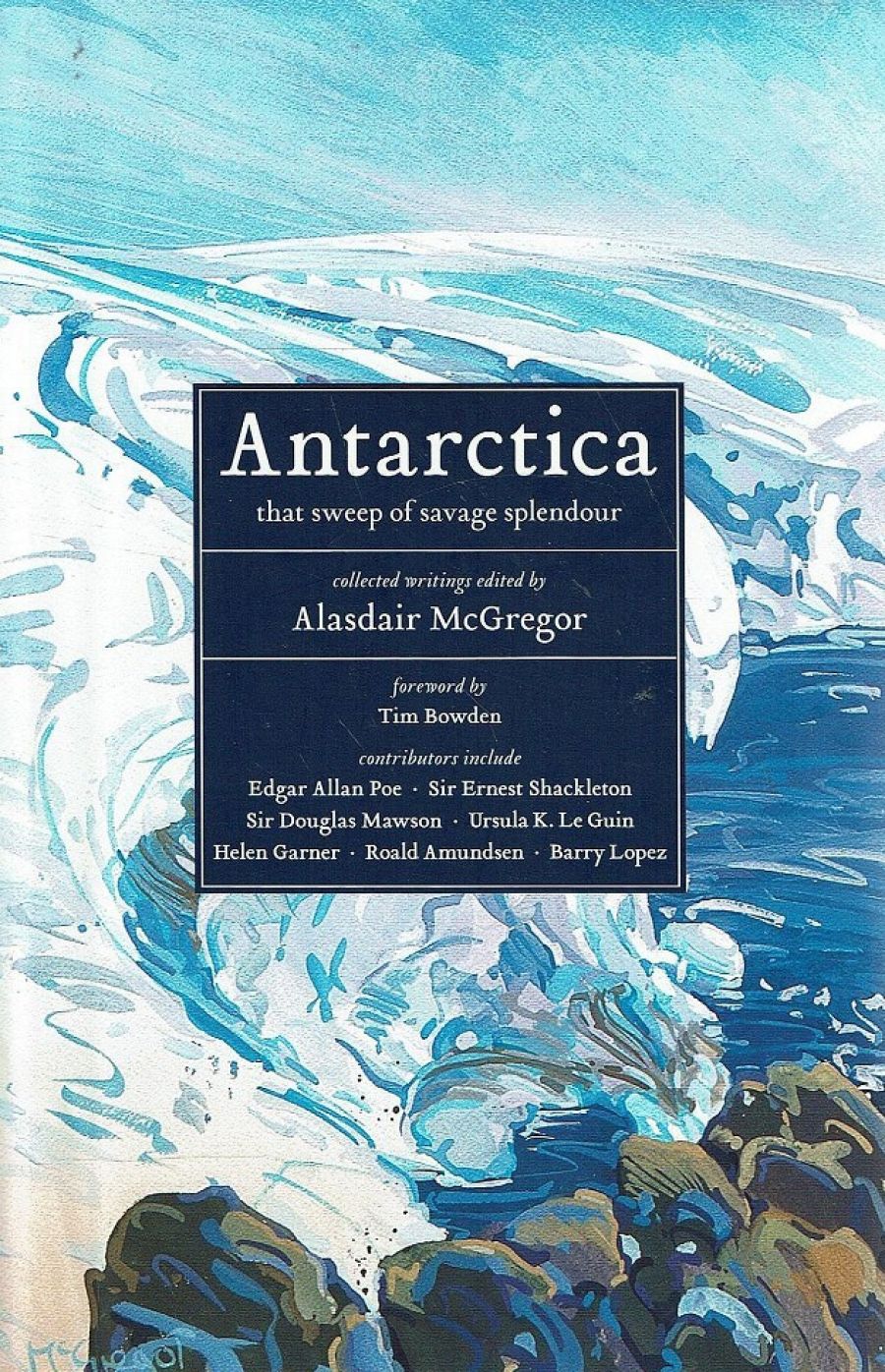

- Book 1 Title: Antarctica

- Book 1 Subtitle: That Sweep of Savage Splendour

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $39.95 hb, 352 pp

That day was not Cook’s first experience of pack ice in the Southern Ocean. A few weeks earlier, on 14 December, he had described being stopped by ‘an immence field of Ice to which we could see no end’, an experience repeated several times in the intervening weeks. But it is difficult not to hear something special in Cook’s description, an intimation of the manner in which the southern continent exercises our imagination, its emptiness and absence simultaneously entrancing and refusing our advances.

Cook’s journals are not included in Alasdair McGregor’s splendid new anthology of writings about Antarctica. In their place, McGregor offers an excerpt from the account of gunner’s mate John Marra, whose unauthorised, ghost-written account of the Second Voyage beat Cook’s into print by several months, and thus enjoys priority as the first published eyewitness account of the continent. Yet the collection as a whole is shot through with the odd combination of pragmatism and wonder that one hears in Cook’s words, the tension between the surrender to the sublime and the spirit of scientific enquiry that enlivens so much of the best writing about Antarctica, and a pleasing resistance to the mythologising impulse that afflicts so much of our thinking about it.

This dual quality is presumably a function of McGregor’s familiarity not just with Antarctica itself but also with its various cultural representations. Architect, painter, photographer, and author of two previous books about the continent – Mawson’s Huts: An Antarctic Expedition Journal (1998) and the definitive biography of one of the more fascinating and elusive of Australian icons, Frank Hurley (2004) – McGregor has also spent considerable time in Antarctica and its islands, including two stints as the official artist and photographer on expeditions by the Mawson’s Huts Foundation to Commonwealth Bay on the Adélie Land Coast, and, more prosaically, as lecturer, historian, and tour guide on tourist voyages to the Antarctic Peninsula, the Ross Sea, and Adélie Land.

It is also a duality that underpins much of what makes the book so unique and so fascinating. Antarctica, as much because of as despite its isolation, has inspired a rich literature, comprised not just of firsthand accounts of courage and privation by figures such as Scott, Shackleton, Byrd, and Mawson, but also of a far larger body of imaginative works inspired by these stories and their possibilities. There is little doubt, as McGregor points out, that Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner’s descriptions of the ice islands ‘green as Emerald’ were directly inspired by Cook’s account of his encounter with the ice, yet the literary imagining of Antarctica also embraces work by writers as diverse as Edgar Allen Poe and the creators of Marvel Comics’ Savage Land.

Faced with such a plethora of writing, the anthologist’s challenge is to sidestep expectations, not just by finding new, less familiar works, but also by finding ways to let us see work that is already familiar in new, surprising ways.

It is to McGregor’s credit that he has been prepared to do just this, deliberately rejecting the mythologising impulse in place of something both more gregarious and immensely more interesting. Again and again the book offers up voices and images that allow the reader to see Antarctica anew. Part of this is about the range of voices, many of which may be new even to those familiar with the literature of the continent. Although I knew American ornithologist Robert Cushman Murphy’s sadly neglected but harrowing 1912 account of his journey to the whaling stations of South Georgia, and of the industrial slaughter he witnessed (an account that cannot help but evoke Melville’s infernal description of the Pequod ’s try-works in Moby-Dick), other pieces, such as Bill Green’s breathtaking and brilliant fusion of cultural history and poetic speculation, ‘The Map’, and Stephen Pyne’s precise, almost architectural description of the Polar Plateau, ‘The Sheet’, were new to me.

McGregor is unafraid to omit writings that others might regard as essential, or to make unconventional choices when it comes to more iconic accounts. The decision to include Mawson’s peculiar short story ‘Bathybia’, with its overtones of Wells and Verne, rather than a selection from The Home of the Blizzard (1915), gives a rare, oddly personal glimpse of this remote figure, and resituates him in a cultural context it is too easy to abstract him from.

This is not to say that McGregor’s choices are always successful. Despite my considerable admiration for Adrian Caesar’s speculative re-imagining of Scott’s last journey, The White (1999), to use an excerpt from it in preference to Scott’s actual diaries seems curious, to say the least (although the decision to use Melinda Mueller’s dramatic monologue in place of Shackleton’s account of the journey to South Georgia bears surprising fruit in its final lines, as the shattered figures of Shackleton and his men appear like wraiths before the astounded South Georgians). Likewise, the decision to give over most of the plates to reproductions of McGregor’s own art, rather than Hurley’s photographs of the Endurance expedition, diminishes both.

What makes McGregor’s collection absorbing is the fact that the unconventional nature of his choices is tied to a larger and more subversive attempt to wrest our imagining of Antarctica back from the images of noble sacrifice and doomed bravery we so readily associate it with. As the inclusion of Ursula Le Guin’s darkly comic account of the first female-only expedition to the Pole suggests, McGregor is alive to the manner in which female experience is too often elided by heroic narratives. As Le Guin’s narrator observes, ‘the backside of heroism is often rather sad: women and servants know that’.

Alongside the book’s interest in the domestic nature of life in the south, evident in pieces such as Jean-Baptiste Charcot’s description of his 1909 expedition, this alertness to non-male, non-imperial experiences enlivens Antarctica. It also lays the groundwork for the shift that is discernible in the book’s latter part, when the rolling thunder of the early writers is supplanted by more contemporary voices, alert not only to the grandeur of the landscape but also to its particularity, and, more importantly, its vulnerability.

Here, the book assumes its real importance. As Meredith Hooper writes in the haunting excerpt from her book The Ferocious Summer (2007), the Antarctic is a microcosm of the larger catastrophe that is rising around us, the assault on its ecosystems a precursor to a much larger process of change we still seem unable to understand or to avert.

McGregor is too sensitive an editor to labour the point, but in the pieces by Hooper and Bill Green that close this remarkable, often magnificent, collection, these questions assume a new significance, underlining the sheer scale and importance of what is taking place by directing our eyes to the Antarctic’s role as a climatic bellwether. As McGregor writes in his introduction, the Antarctic’s ice sheets are in a very real sense ‘immense libraries of … change constructed over geological time’, which in their memory of the great cycles of time cannot help but remind us how closely ‘Antarctica and survival are bound together in the same eternal sentence’.

Comments powered by CComment