- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Photography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

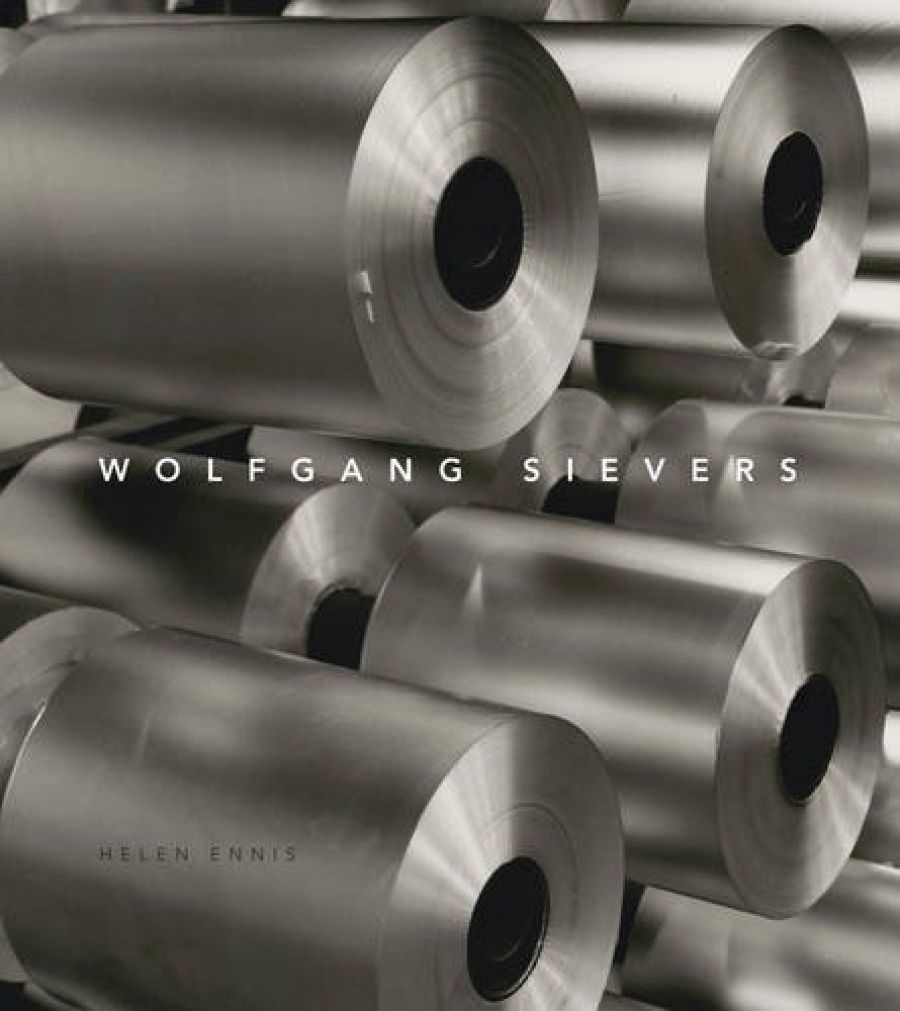

Wolfgang Sievers was a complex person with a clear vision. The major dimensions of his life included photography and an abiding sense of the dignity of man. Helen Ennis, one of the foremost authorities on Sievers, has produced a book that is at once satisfying and teasing.

- Book 1 Title: Wolfgang Sievers

- Book 1 Biblio: National Library of Australia, $49.95 pb, 196 pp

The book is really a monograph about Sievers’s life and work, and a selection of his photographs. The reproductions are very fine, and there is much satisfaction in studying them and appreciating his great sense of modern design. But the book teases us as well. It gives just the briefest taste of Sievers’s early work. Before coming to Australia as a refugee in 1938, he had worked at Contempora in Berlin. The book includes one of his advertising photographs from that period. It is a photograph taken for Elbeo stockings, a beautiful image which somehow evokes Mona Lisa, without a hint of imitation. But Wolfgang Sievers does not include any other of his remarkable advertising photographs taken while he worked at Contempora, images that are timeless and compelling, and which stand apart from any of the work he later did in Australia: for example, his Advertisement for Agarol (1938), with its sculptural simplicity, and his Advertisement for Banking (1938), which confines itself to an authoritative pair of hands and an elegant fountain pen.

Similarly, it is a pity that this publication contains only one image from Sievers’s time in Portugal. True, it is the finest of his Portugal photographs, Saltfields of Marques de Pombal (1934), but how frustrating that we do not see some of the photographs from his stays in Portugal in 1934 and 1935, which prefigure his later work on the theme of the worker, and for that matter some of the fine architectural photographs from his time there. Not as powerful as his later architectural photographs, but a marker of the start of the journey.

Most of the images in the book are drawn from Sievers’s Australian work between 1938 and 1985, when he retired (he died in 2007, aged ninety-three). The images are grouped by their major themes: Architecture, Industry, the Worker, and Mining.

In several of these sections, the selection of work is both satisfying and teasing. For example, in the section on architecture, the book includes iconic photographs of the new Olympic Swimming Pool (1956) in Melbourne and the Stanhill flats (1951). Also included are a number of interiors, which, though technically skilful and no doubt commercially suitable for the client, rank well behind a number of other architectural photographs which are not included. We do not see the Edifice of the AMP Building (1970), in which the great Clement Meadmore sculpture is completed by its own reflection in polished granite, or the striking photograph Two Buildings (1960), taken from the ground looking vertically upwards. Neither do we see his early architectural photographs from Berlin: perhaps not as great as his later work, but interesting because of his origins in the classical style before his journey into modernism. And perhaps there was a place here for the Cottage at Aldinga (1976), with its surprising painterly quality.

The selection of images from ‘Industry’ is, to my mind, much more satisfying. All thirty images in that section are magnificent. While dozens of other images could easily have justified inclusion in this section, the selection which has been made can hardly be faulted. Although reproduced in the introductory part of the book, we also get the famous Gears for the Mining Industry at the Vickers Ruwolt Factory (1967). The principal image – two vast half-gearwheels, one suspended above the other in an incomplete figure eight, with an engineer standing on the lower piece measuring with a Vernier caliper – is the most famous of Sievers’s images (it was featured on the forty-three cent stamp in 1991). There is a second image taken at the same time. This time, the engineer is on the ground; this image is also reproduced. Sievers spent more than eight hours setting up for these photographs, to realise a design he had conceived in his mind when he saw the central elements – two grimy half-wheels – lying on the floor of the factory. He had them cleaned and put in place. He arranged the lighting: strong light from the side, weaker light from the front (‘not original – Rembrandt did it’); he persuaded an engineer to climb onto the lower of the gears. After all this setting up, he took just two images. Little wonder that his final collection of photographs was called ‘Born to See’.

It is in the section titled ‘The Worker’that both major characteristics of Wolfgang Sievers come together. He was passionate about the dignity of man, and in this section are included some of his best-known works, including the Miller Rope photograph (his personal favourite and the best known of his photographs), which was commissioned by Australian Pulp and Paper Mills.

While the photographs in this section are fine examples of photography and design, they are also interesting for a different reason: they show aspects of Australian industrial labour which have now disappeared. They are not just great photography, but are also fascinating history. Most notable in this respect is Shift Change at Kelly & Lewis Engineering Works (1949); it evokes times and circumstances which have entirely vanished.

Sievers’s passionate interest in human rights was famously expressed when he displayed in his Collins Street window a photograph of a US soldier holding the head and flayed skin of a dead Vietnamese child. Sievers lost a lot of friends for that gesture of protest. At the end of his life, he asked me to accept most of his remaining photographs, with a request that I use them to raise money for human rights causes. The gift included some of the finest images from across his entire career. At an exhibition of some of the works shortly before he died, he made a speech of just one word. He shuffled to the microphone, paused, and said ‘Compassion’.

So far, the sale of photographs from the collection has raised more than $350,000. It keeps his work and his vision alive. He would be quietly satisfied to see the results. And he would be pleased with Helen Ennis’s book, which speaks truly of the man and of his work.

Comments powered by CComment