- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A cluttered portrait inevitably diminishes its subject. I am thinking, in particular, of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm in his gallery in Brussels, by David Teniers the Younger, in which the Habsburg aristocrat is like an ant among his scores of pictures. This happens with biographies, too. A satisfying example is far more than an expansion of the subject’s curriculum vitae or a thorough examination of his appointment diary. When the author has strong feelings (as a widow inevitably does), the problem is aggravated. This new biography – of an extraordinary musician who might, in different circumstances, have contributed far more to Australia than he was allowed to do – is both partisan and prolix, and is as littered with quotidian details as the Teniers painting is with canvases. In both cases, these objects and details are too small to engage our attention usefully or thoroughly.

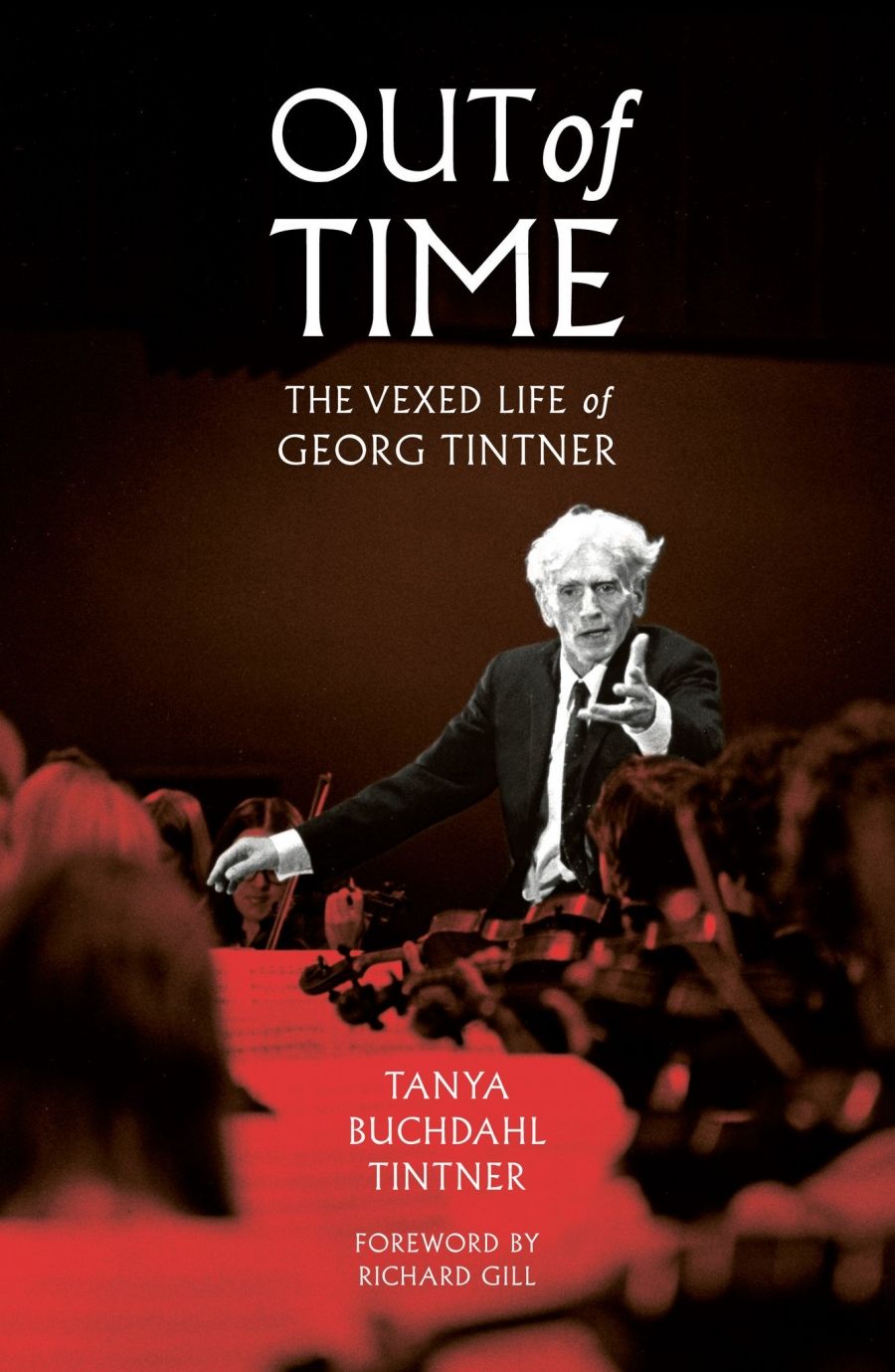

- Book 1 Title: Out of Time

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Vexed Life of Georg Tintner

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $39.95 pb, 448 pp

We get Georg Tintner the frustrated composer, but the author seems to lack the technical knowledge or explicative capacity to do more than repeatedly reinforce Tintner’s grumbles about his nugatory achievement. We get Tintner the insatiable philanderer, although, as with his Ahasuerus-like geographical wanderings, the implication is that the ‘blame’ lies with others. We get Tintner the vegetarian zealot as some sort of spiritual purist, though people who smelled his cooking thought less nobly of this dedication.

In fact, when I first met him, in 1961 or 1962, Tintner was sitting in a corner of a musician’s house in Brisbane, munching nuts and sultanas from a brown paper bag and looking just as gaunt and grey-haired as in the photographs taken close to the end of his life forty years later. As I was soon to discover, he had the loneliness of the long-distance cyclist.

Put him in front of an orchestra or in an operatic pit, however, and that seeming frailty disappeared. When combined with his musicality, his energy and passion could make for incandescent performances that he loved and honoured. These capacities grew out of his experience of growing up in Vienna – the son of Jews who had converted to Lutheranism – his membership of the staunchly Catholic (and anti-Semitic) Vienna Boys’ Choir, and his enviable familiarity with the work of such conductors as Franz Schalk, Bruno Walter, Otto Klemperer, Arturo Toscanini, Richard Strauss, and Wilhelm Furtwängler.

Little of that cut much ice in the early 1940s when he found himself a refugee in New Zealand, with an English lover (soon enough his respectable, poultry-farming wife); he was not allowed to play the piano on national radio lest he send coded messages through the music, and in his occasional salon recitals he was shocked to encounter people who clapped after a few minutes because they considered his pieces too long.

Not much improved when he came to Australia in 1954. It is chastening to read the extracts from ABC files, in particular, which the diligent author has located. While Tintner had some supporters – the highly accomplished German Werner Baer, for example – many others were petty and punitive. Michael Corban, who had trained as a conductor, but who lacked the personality for that role, seemed bitterly jealous, to the point of appearing to sabotage Tintner’s prospects (remember: the ABC then controlled all of Australia’s professional orchestras). The composer and conductor Richard Mills is quoted as saying that Tintner was ‘one of those central European parasites’ who kept perfectly good Australians out of a job, though, significantly, the author attributes this information only to ‘an orchestral associate’, whom she does not name (this illustrates one of the paradoxes of the biography: while there are many endnotes, repeatedly the book lacks documentation of important assertions and opinions). Furthermore, she frequently fails to mention Tintner’s important collaborators, as if she is unwilling to let them share his successes. Like excessive detail, such a narrow focus inevitably diminishes her subject.

It has to be conceded that, to resort to a tired phrase, Tintner was really his own worst enemy. This is not because of his insatiable drive to bed women (unsurprisingly, that produced its own complications), but because he was unwilling to compromise, especially about the rightness of his musical opinions, though there were astonishing lacunae in his tastes. Solipsistic is the apt word for his personality, and, when blended with a lack of tact with his colleagues, it certainly made bitter disappointments inevitable in a society and culture that he never came to understand.

Some of his colleagues certainly deserved short shrift, especially when they held power despite their musical knowledge and capacities being inferior to his own. His shabby treatment by David Macfarlane, the political and musical power-broker who ran the Queensland Lyric Opera, is well worth documenting, and the account of Richard Bonynge’s appointment as musical director of the Australian Opera, which the author elicited from John Winther, then its general manager, is refreshingly frank. ‘For [Georg] this was a disaster, not least because he thought Bonynge would change the Opera’s repertoire to a diet of second-rate bel canto operas to suit himself and his wife [Joan Sutherland] … John Winther had broken his word that Georg would have no musical director above him … Winther admits, “I appointed Bonynge and Sutherland as a political move. Everyone wanted Joan, and he came with the package … Georg leaving was an unintended by-product.”’ Winther was, without doubt, the best-qualified chief executive that our opera has had, but he was fallible in his ethics. Those were times when Australia had within its grasp the chance to progress from musical and operatic insularity to a far richer condition; until that happened, the flaws of such gifted people as Winther and Tintner gave their lesser colleagues opportunities that few had the strength of character to resist.

In 1955 the eminent composer and educator Alfred Hill (himself a refugee from New Zealand) unsuccessfully recommended Tintner to the Queensland government as the first director of its new Conservatorium (they appointed a dull Englishman). ‘I think this musician is of such a stature,’ he wrote, ‘that you should send for him … He is more than good. He is a genius.’ Tintner’s intellectual gifts and defects of character jostled and rubbed against each other in the manner of great tragedy. His story is almost Shakespearean in its scope and possibilities. His widow, alas, is no Shakespeare.

Comments powered by CComment