- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Young Adult Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Stephen Mansfield reviews 'The Dead I Know' by Scot Gardner and 'The Comet Box' by Adrian Stirling

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The way nostalgia works, according to theorists, is that we pine for the era just before our own. This may be why the twenty-something musicians of today mine the sounds of the 1980s. But does this pattern succeed in Young Adult fiction? What does an author gain by setting his or her story in the ‘nostalgia zone’ of potential readers?

- Book 1 Title: The Dead I Know

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $19.99 pb, 208 pp, 9781742373843

- Book 2 Title: The Comet Box

- Book 2 Biblio: Penguin, $19.95 pb, 259 pp, 9780143206101

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_SocialMedia/2021/September_2021/META/10055722.jpg

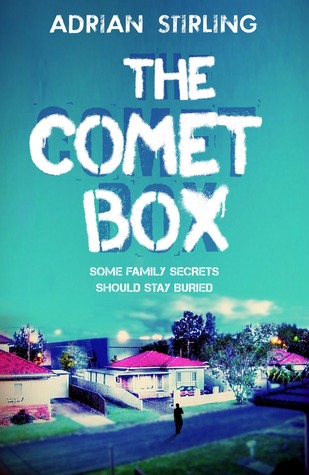

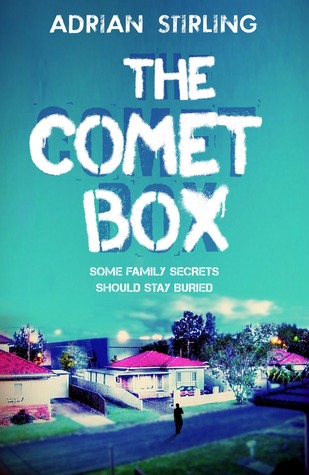

Some recent titles suggest that there is something to be gained. Sonya Hartnett’s brilliant Butterfly (2010) gave us the Australian suburbs of 1980, and the setting leant her novel a kind of time out of place. Adrian Stirling may be aiming for the same effect in The Comet Box. Set during summer in the mid-1980s, Andrew and his friends eagerly await the arrival of Halley’s Comet. Andrew also desperately wants his older sister to come home before Christmas. Since she ran away after a fight with their parents, nothing has seemed right in the suburb of Merton.

Stirling’s depiction is anything but nostalgic. There is a meanness to his sweltering 1980s suburbia that is oppressive and almost garish: the men drink VB, the women West Coast Coolers, and Andrew and his best friend Romeo wander the empty streets looking for something to do. As the narrator notes, ‘In Merton our streets were named after astronauts and sporting stars […] but by the time you were six you already knew that greatness was meant for other people.’ The excellent cover design, a suburban grid illuminated by alien light (perhaps from the comet), encapsulates this setting perfectly.

While Stirling’s description of this monochrome world creates a tone for his novel, the reader begins to crave some variety or texture in the narration. Those readers who, like the author, grew up in the 1980s might find themselves thinking, ‘Surely it wasn’t this stultifying!’ Sometimes the first-person narrative voice in teen fiction seems to act as an excuse for dull writing.

When the police find Amelia and bring her home, Andrew’s hopes of a cheery Christmas are thwarted by how she has changed. Waifish and undernourished, Amelia has become hard-edged. She snipes at the rest of the family, determined not to let her parents forget the dark secret that made her run away in the first place. As Andrew slowly learns more about this and other secrets in his neighbourhood, he must confront his sister’s challenge to face the truth about their world: ‘People convince themselves that everything is okay when it’s rotten to the core. I can’t pretend it’s okay, Andrew, and I won’t let them pretend either.’ Stirling’s boldly ambiguous ending prompts readers to wonder whether, as his tagline suggests, some secrets really should stay buried.

Scot Gardner’s The Dead I Know is set in no particular time or place; an unnamed seaside town in the off-season. Aaron Rowe lives in a caravan park with an older woman he calls ‘Mam’. She is clearly in the latter stages of dementia, though Aaron is doing his best to hide this. Aaron’s school counsellor saves him from the grinding ignominy of school by recommending him for an apprenticeship with the local funeral director. To everyone’s surprise, Aaron takes to the work with ease; he enjoys the formality of the job and the art of bringing dignity to the dead. At the same time, the bodies he helps prepare for burial and the raw emotions of the funeral services begin to stir something he has repressed for a long time.

Few stories focus so intensely on the minutiae of a body’s journey after death. The television series Six Feet Under is an obvious comparison here, though the way Gardner sets out a kind of poetics of dealing with the dead is reminiscent also of the film Japanese Story. After spending hours scouring the side of a highway for the head of a motorcyclist, Aaron muses on the process of caring for the deceased: ‘although we’d been conducting the same search, the policemen were hunting mortal remains to finish a job, I was hunting the still countenance of someone’s son, perhaps their brother, maybe even their father, to bring him a final grace.’

While Aaron’s job gives his days a purpose, his nights are complicated by a bad case of somnambulism, brought on by a recurring nightmare. This nightmare, which is basically the image of a woman’s body on a bed, is revealed in snippets at the beginning of Gardner’s chapters. Aaron tries hiding the caravan key and tying himself to his bed, but each morning he wakes in a strange new place. Most disturbingly of all, his sleeping self seems increasingly drawn to the sinister world of his neighbours in van 57.

Gardner’s protagonist, affable but damaged by something in his past, is a fascinating creation. His boss’s daughter takes to calling him ‘robot’ due to his lack of engagement with the world. A taciturn teenaged boy is a surprisingly useful narrator, however, as he lives almost entirely in his own head. Aaron’s sharp observations and witty interior monologue serve Gardner well, lightening what is an incredibly bleak story. But the best thing about The Dead I Know is the character of John Barton, the funeral director. Gardner’s depiction of a genuinely good man, whose attention and care change Aaron’s world irrevocably, is a triumph. That his generosity may be motivated by his own tragic past fails to lessen our admiration of his goodness.

The author claims John Marsden, who contributes a glowing cover endorsement, as a mentor, and in Gardner’s tight control over language and tone there is something of the older writer’s ability to enter the minds of his protagonists. But Marsden has not written anything quite as dark as this. Gardner’s prose leaps off the page courtesy of a rough-hewn poetic simplicity, recalling Markus Zusak’s early novels, such as his Underdog trilogy.

While the narrative is always building towards a terrible unveiling, where a series of traumas finally unearth Aaron’s repressed memory, the final gruelling pages of the novel feel overdone. We may draw comfort from knowing that Aaron will begin to heal from here, but the book would have invited a more empathetic readinghad its climax not been so extreme. As The Comet Box demonstrates, smaller injustices can be just as hard to recover from.

Ultimately, both books ask us what we should do with the destructive things in our past, though their narrators arrive at different solutions. Once Aaron finally faces his repressed memory, his robotic demeanour evolves into a healthier engagement with the reality of his present, including Mam’s dementia. Andrew and his parents, on the other hand, choose to go on ‘living without remembering’. Amelia, the only character in The Comet Box who decides not to pretend, is treated abominably and heads off into a very uncertain future. Perhaps this accounts for Stirling’s 1980s suburbia and Gardner’s no-place-in-particular. In giving us distance from these worlds, the authors cause us to hope that such clearly damaged young people would not fall through the cracks these days.

CONTENTS: SEPTEMBER 2011

Comments powered by CComment