- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Korea

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Roads not taken

- Article Subtitle: Korea’s postwar period

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the late hours of 3 December 2024 South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol declared martial law in response to what he claimed was a ‘legislative dictatorship’ directed by ‘anti-state forces’. In shocking scenes broadcast around the world, citizens took to the streets in protest and mobilised army units defied orders to suppress dissent. Meanwhile, 190 legislators from both parties forced their way into the National Assembly to unanimously vote down the martial law declaration. It was rescinded just hours later, and the disgraced president was subsequently impeached and unceremoniously removed from office.

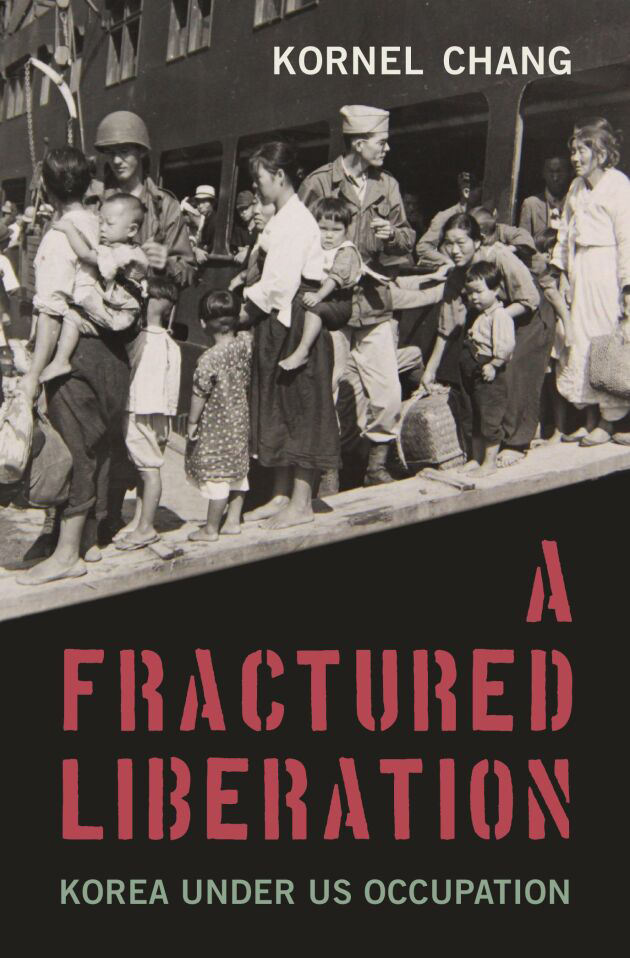

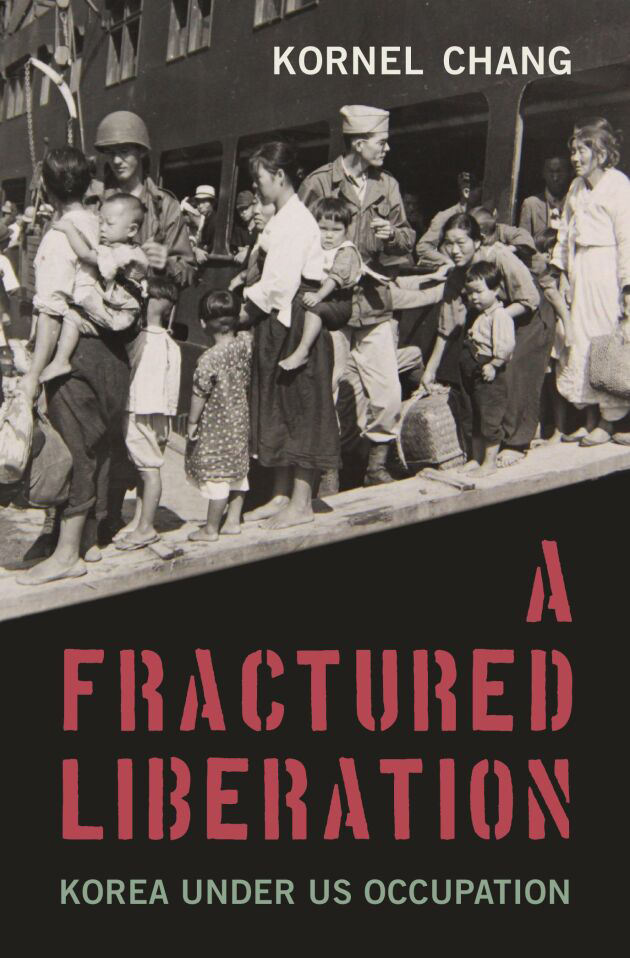

- Book 1 Title: A Fractured Liberation

- Book 1 Subtitle: Korea under US occupation

- Book 1 Biblio: Harvard University Press, US$29.95 hb, 304 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780674258433/a-fractured-liberation--kornel-chang--2025--9780674258433#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Chang’s book sets out to uncover roads not taken, ‘key moments where a different choice, firmer resolve, and a twist or turn in favour of unity, could have led to alternative outcomes … and how and why these key moments became missed opportunities’. By and large, Chang is successful in this undertaking, providing a succinct, engaging, and at times emotionally charged work firmly grounded in relevant primary sources. Chang’s book is especially effective at highlighting how the ignorance of Korean affairs among occupation personnel and the intransigence of US Lieutenant General John Hodge in managing the occupation created the conditions for authoritarianism later.

In the introduction Chang provides necessary colonial context for the liberation and occupation periods. Slightly more detail and nuance related to this crucial period would have been helpful in better understanding the particular milieu in which the American occupation operated. The colonial period tends to lurk in the background as a political monolith or potential mechanism of control that American policymakers selectively maintained out of ignorance or fear of communism, rather than as an entire frame of modernity, which it had become by 1945.

Chang, for example, repeats the common refrain that ‘Japanese colonial policies to “assimilate” Koreans were not terribly successful … less than 20 percent of Koreans were fluent in Japanese by 1945’, but this assumes complete fluency as a yardstick for ‘success’. Coming from a baseline of virtually zero Japanese language competency in Korea in 1910 (setting aside that practised by a thin stratum of the élite), one could argue that twenty per cent fluency in thirty-six years was not an insignificant number, especially considering that among the male urban population who received schooling in Japanese – the same individuals who became instrumental in shaping post-liberation South Korea – well over ninety per cent spoke Japanese by 1945. However, little attention is given to this broader cultural and linguistic colonial legacy, one area where Bruce Cumings’s rich introduction to The Origins of the Korean War (1980) still offers keen insights.

In Chapter One Chang does an excellent job of weaving liberation-era Korean fiction into his own historical narrative, infusing the work with an engaging human tone. This chapter, however, would have benefited from some discussion of this approach to history. Although history does benefit from fictional narrative, the narratives are just that – fiction – and from an emotionally and ideologically charged period prone to bias. Some contextualisation of these fictional accounts and their utility for the historian would have been helpful.

In subsequent chapters Chang is on surer footing, presenting, for example, a revealing account of the fight for land rights by various groups and the dismissal of such claims by an intransigent American command. Moreover, Chang effectively shows the irony of America’s occupation in East Asia, highlighting how Korea, a colony liberated from Japanese occupation by the Americans, got a much more brutal occupation than Japan, a vanquished foe. According to Chang, much of this can be attributed to the wartime leadership styles of John Hodge in Korea and US General Douglas MacArthur in Japan, where the former remained ‘rigidly principled and uncompromising’, and the latter, despite being a ‘staunch, Anti-New Deal Republican’, oversaw, in the immediate postwar period, a robust agenda in Japan of workers’ rights, land redistribution, universal suffrage, and permanent disarmament. This starkly illustrates the outsized influence of American power and personnel at this historical inflection point.

Chang does an excellent job of highlighting the machinations of President Syngman Rhee to successfully move the south from a parliamentary system in 1948, as originally envisioned, to a presidential one with few checks on power – a move that continues to haunt South Korean politics today. Chang reminds us that Rhee’s ascent was not by virtue of American backing, but actually in spite of American resistance; that it resulted from a combination of Rhee’s virtuoso political manoeuvrings and the inability of US command to find a better alternative in the context of a tight deadline for impending withdrawal in August 1945. Chang also makes the important point that, ‘as an imperial president, Rhee radically redefined who and what a “collaborator” was. They were no longer individuals who abetted and profited from Japanese colonial rule. They were now pro-Communist sympathizers.’ This is a revealing counterpoint to the songbun system for determining loyalty to the regime that emerged in the north and endures today.

US General Edward Craig and South Korean President Syngman Rhee, 1950 (Everett Collection Historical/Alamy)

US General Edward Craig and South Korean President Syngman Rhee, 1950 (Everett Collection Historical/Alamy)

Due to the sheer size and importance of Cumings’s history, Chang’s work naturally invites comparison. Chang takes a similarly dim view of the American occupation, at times painting an even more astonishing and dismal picture of American ignorance and incompetence than that presented in Cumings’s damning portrayal.

Three points of similarity in particular stand out: first, most Koreans were not really aware of, or beholden to, political labels like ‘liberal’ or ‘communist’ and rather subscribed to a wide range of ‘socialist democratic’ policies that sat somewhere in between. Secondly, the choices made in the final months of 1945 (mostly by American personnel and especially by Hodge) created the conditions that made it difficult to avoid intractable authoritarianism and war. Finally, these same decisions during the early months of the occupation foregrounded later developments in the Cold War; it was as if events in Seoul dictated policy in Washington years later. Chang is to be credited with driving home these points in a clear, succinct, and highly engaging manner, though his book lacks the rich archival detail of Cumings’ volumes.

A Fractured Liberation is an engaging, highly readable, and compelling portrayal of the American occupation of Korea and its clear implications for the Korean Peninsula today.

Comments powered by CComment