- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: ‘“Come nearer to Asia”: Australia’s place at Bandung, 1955’

- Review Article: No

- Article Title: ‘Come nearer to Asia’

- Article Subtitle: Australia’s place at Bandung, 1955

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The seventieth anniversary of the 1955 Asian-African Conference held in the city of Bandung, West Java, Indonesia, passed earlier this year without evident note in Australia. In Asia and Africa, it was the subject of commemorative conferences and gatherings, impassioned speeches and articles. In Bandung itself, a ‘Global History and Politics Dialogue’ heard from Indonesia’s Deputy Foreign Minister and numerous other serving and past parliamentary leaders that the Bandung Spirit is ‘ever more relevant today’. In India, the prominent economist C.P. Chandrasekhar said that ‘seventy years after Bandung, the Global South is still waiting for independence’ and the Bandung Spirit must be revived. For the Global Times of China, what we make of the historical ‘inheritance’ of Bandung is ‘a matter of practical choices’.

In Sri Lanka, Lebanon, Morocco, Thailand, Zambia, Pakistan, and Iran, this idea of the continuing direct relevance of the Bandung spirit, or legacy, was echoed. From South Africa, Deputy Minister of International Relations and Cooperation Alvin Botes wrote: ‘The Bandung principles offer … an essential blueprint for a more just, inclusive, equal, dignified and peaceful future. The spirit of Bandung, solidarity among the oppressed, South-South cooperation, and an equitable, inclusive, just, peaceful, stable and sovereign global order – remains urgently relevant.’ Even Lula da Silva, President of Brazil, a country from a continent not represented at the Bandung conference, suggested in July this year that the BRICS bloc of nations also ‘carries the spirit of Bandung’.

The Asian-African Conference in Bandung took place across 18-24 April 1955. The dates weren’t entirely arbitrary for April 18 marked the one-hundred-and-eightieth anniversary of the famous midnight ride by Paul Revere to initiate the American War of Independence. In his opening address, now also famous, Indonesian President Sukarno celebrated Revere and this ‘first successful anti-colonial war in history’. Though, as the Indonesians well knew, the Americans were unhappy to not have been invited to the conference, the head of the secretariat Roeslan Abdulgani was relieved to observe a beaming US ambassador Hugh Cummings striding towards him, immediately after Sukarno’s address, hand outstretched. It was only the following year, the highly competent but suitably nervous Abdulgani recalled, that he admitted to Cummings that the date was actually determined by a short window between Buddhist and Islamic sacred days.

The idea for the conference came from Indonesian Prime Minister Ali Sastroamidjojo, at a 1954 meeting with the leaders of India, Pakistan, Burma (now Myanmar), and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) in Colombo. But as Sukarno noted, and as was observed by Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and others, the real origins of the event went back to the city of Brussels, Belgium, in 1927, and the League Against Imperialism and Colonialism, at which many of those in Bandung first met each other.

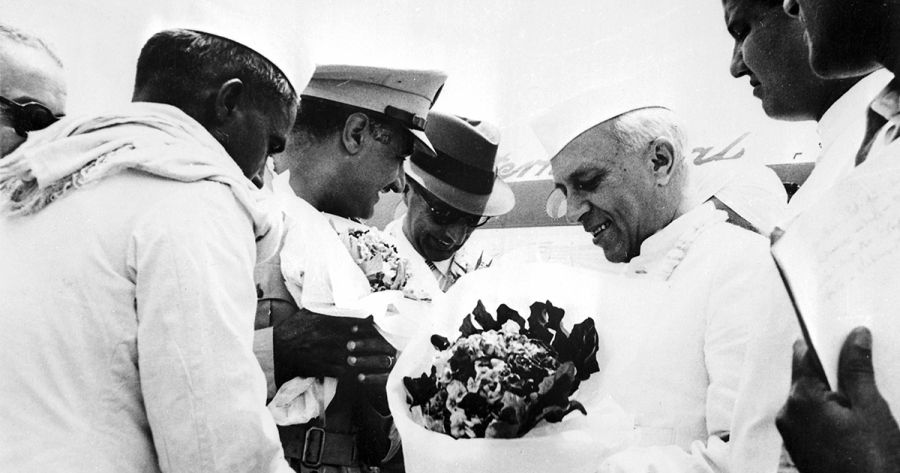

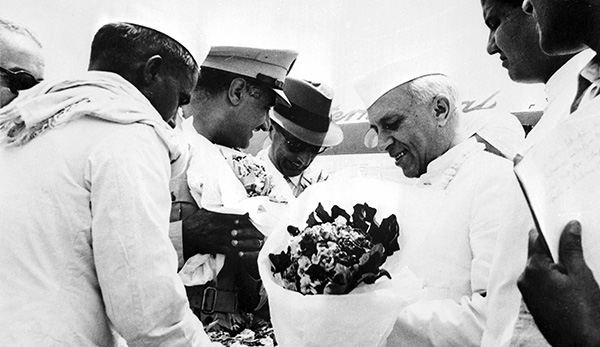

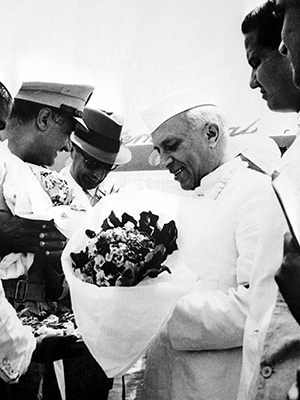

Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Premier of Egypt Abdel Nasser are presented with flowers on their return to India after attending the Asian-African Conference, 1955 (Smith Archive/Alamy)

Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Premier of Egypt Abdel Nasser are presented with flowers on their return to India after attending the Asian-African Conference, 1955 (Smith Archive/Alamy)

The Bandung conference, Sukarno pointed out, marked ‘a new departure in the history of the world’, a postcolonial moment in which leaders of Asian and African peoples could ‘meet together in their own countries to discuss and deliberate upon matters of common concern’. This was the largest gathering of non-European nations the world had seen: twenty-nine of them. The purpose was to discuss shared experiences, ways of cooperating and, most especially, ‘to view the position of Asia and Africa and their peoples in the world of today and the contribution they can make to the promotion of world peace and cooperation’.

The ‘Colombo Five’ sponsor nations had three primary shared diplomatic objectives: to reduce the risk of war between China and the United States; to strengthen China’s impulses towards independence, against any closer partnership with Soviet Russia; and to reduce any risk of conflict – direct or via proxies– between China and themselves and their Asian neighbours. The Colombo Five, along with the great majority of attendees, believed by the conference’s end that these objectives had been achieved.

China’s Premier Zhou Enlai impressed attendees and observers with his openness, diplomacy, and capacity to connect with and set other attendees at ease about the intentions of his nation. As part of this accomplished diplomatic manoeuvring – wrinkled only by a blow-up with Ceylon’s Prime Minister, Sir John Kotelawala, who plonked Soviet imperialism on the conference agenda – Zhou publicly offered to sit down with his American counterparts to talk through the vexed issue of Taiwan, already of grave concern for the leaders and peoples of Asia.

Zhou’s poise appears all the more remarkable given that he had just avoided, we now know, an assassination attempt. Secret service agents from the Nationalist Republic of China regime in Taiwan had planted a bomb on the plane destined to take Zhou to the conference. Communist Chinese intelligence discovered the plot and ensured that Zhou was not on board when the Kashmir Princess, lent by Air India, exploded and crashed after leaving Hong Kong.

That the Americans refused Zhou’s offer to discuss Taiwan was seen as profoundly disappointing and unwise by attendees, including even the German ambassador and the High Commissioner of the Netherlands, who reportedly considered this response ‘especially maladroit even for American diplomacy’.

The Non-Aligned Movement which, with 121 members, exists today as the largest national grouping outside the United Nations, is generally seen as having grown out of the Bandung gathering and arguments advanced there by Nehru in particular. (Arguments which were not accepted by Pakistan and a number of other delegations, who felt they needed the protection of powerful friends.) Coming out of Bandung, and the calls there for increased international democracy, there was a dramatic increase in the number of newly independent nations joining the United Nations. By 1975, total UN membership had grown from seventy-six to 144.

It is not surprising that this Bandung anniversary, like earlier ones, occasioned little enthusiasm in Australia. Australia was not invited to attend the conference and, under Prime Minister Robert Menzies, did not want to be invited. At the same time, the government did not want this to be known, so diplomatic efforts were made to prevent an invitation being extended.

But perhaps a deeper reason is that the view of the world reflected in the notion of the Bandung Spirit does not easily fit with prevailing frameworks for understanding international relations and trade in Australia. Where Bandung attendees saw the world as shaped by colonialism and neocolonialism, by the domination and exploitation of some nations by others working arm-in-arm with multinational corporations, in Australia the talk is of level playing fields and a benign, positive, decentred, and essentially non-political thing, ‘globalisation’. Like the creators of the colonial Dutch Ethical Policy in Indonesia, at the start of the twentieth century, most Australian leaders accept the assumption that increased development from foreign capital in the long run benefit locals as well as foreign investors.

There was, however, much interest in Australia in this major international gathering on the nation’s doorstep at the time it was held. Journalists from the Sydney Daily Telegraph and the Melbourne Herald and Argus attended and provided reports. Dennis Warner for the Herald and Peter Russo for the Argus were critics of the White Australia policy and wanted the nation to develop closer ties with Asia.

Other Australians attended as well, at their own expense: notably the courageous ANU Professor of Far Eastern History C.P. Fitzgerald and the couple John and Cecily Burton. John Burton, a London School of Economics-educated economist and a member and, from 1947 to 1950, secretary of the Department of External Affairs, was a key figure in Australia’s support for Indonesia and decolonisation more generally at the end of World War II.

John had met Nehru on a diplomatic mission in New Delhi in 1949 and the two men had come to like and respect each other. To the pronounced annoyance of Australia’s Indonesia Ambassador Walter Crocker, journalists reporting on happenings at Bandung from Australia, and Prime Minister Menzies himself, John, Cecily, and Fitzgerald were given special ‘observer’ status and preferential conference seating, accommodation, and transport.

Bandung for Cecily was a highlight of her public life. Commencing with her request that they be served local and not Dutch food, she worked as a valued partner in this unofficial diplomatic mission. She was, however, along with John and Fitzgerald, the subject of great suspicion and disapproval. Menzies asked the ANU to refuse Fitzgerald’s application for leave to attend the conference and rang him to suggest the Vice-Chancellor should go in his place. Colonel Spry, the head of ASIO, had full rein to indulge his obsessions in Canberra and, with Burton and his family, indulge he did. As black cars, trench coats, sunglasses, and notepads were frequently evident, Spry became for the Burtons and their children a household joke, with John being known to greet historian Manning Clark on the phone with ‘Spry here!’

John thought the conference marked the ‘start of the end of the Cold War’. This was consistent with his thinking advanced in a remarkable book published with the small Sydney press Morgans Publications in 1954. The Alternative: A dynamic approach to our relations with Asia alludes in its title to its author’s different understanding of the contemporary world: in the colonial terms of the Bandung attendees rather than the Cold War terms of the Americans and Menzies.

Burton, a confidant and adviser during Evatt’s and Australia’s consequential contribution to the drawing up of the United Nations Charter in 1946, argued that the real cause of the US opposition to communism and to progressive or redistributive policies (routinely also characterised as ‘communist’) was US dependence on unfettered access to overseas markets and resources for domestic growth and political stability. He saw that dependence as arising from the fact that both of that nation’s major parties favoured policy frameworks facilitating the maximisation of return for producers or business owners over the achievement of other social goals, the most important of which was full employment and, attendant to that, the management of national aggregate demand and economic stability. As Burton was personally aware, it was at the Australian delegation’s insistence at San Francisco, but with strong majority support from around the world, that government promotion of full employment (Article 55) was included in the UN Charter, this foundational document of international affairs and law.

The full employment imperative was, as Burton noted, ignored by US governments. He argued, in passages which recall Keynes’s jeremiad The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919), that this was likely to lead to war: ‘[A]n acute international economic problem … will provoke even more aggressive economic policies, and in practice military policies … Finally, America will convince itself that its only salvation is to fight Communism, even in total war.’

It is thus sobering to reflect that, since Bandung, more than half of the nations in attendance have been militarily attacked by the United States or Israel (a nation which, incidentally, at the time of the conference had strong support from many Bandung nations to receive an invitation), with Australian involvement on numerous occasions. And the standout economic success since Bandung has been China, the nation which most jealously guarded control of its own development path. As Burton predicted, ‘This very ancient country is only now, under Communism, on the road to full economic development.’ Starting from a position comparable with India’s at the end of World War II, China’s GDP is now five times that of India. Burton recalled:

In China before the revolution, Western countries – especially Britain and America – had the opportunity to influence the government and to encourage the development of political, economic and social institutions. They failed to do so, mainly because they found it in the interests of their type of economic system to support an administration which, by universal consent, was corrupt and repressive.

In light of all that has gone since, it is striking that in his closing speech on the final day of the conference, the day before Anzac Day seventy years ago, Nehru said: ‘[W]e mean no ill to anybody. We send out our greetings to Europe and America. We send out greetings to Australia and New Zealand. And indeed Australia and New Zealand are almost in our region. They certainly do not belong to Europe, much less to America. They are next to us and I should like indeed Australia and New Zealand to come nearer to Asia. There they are. I would welcome them because I do not want what we say or do to be based on racial prejudices.’

Seventy years on, Nehru’s invitation, and Burton’s too, still calls to us, however faintly.

This article is one of a series supported by Peter McMullin AM via the Good Business Foundation.

Comments powered by CComment