- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Betty’s career

- Article Subtitle: The many lives of Elizabeth Harrower

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

That Elizabeth Harrower should merit not one but two biographies would have both surprised and pleased her. That the biographies would be published within months of each other, by two Sydney writers and journalists, using much the same source material, would have intrigued her, as it did me. I don’t know Helen Trinca or Susan Wyndham, or who had the idea first, or anything of the anxiety they must have felt at being pipped at the post, or of any rivalry for sources and access to people or documents, but the two books arrived on my desk together.

- Book 1 Title: Looking for Elizabeth

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life of Elizabeth Harrower

- Book 1 Biblio: La Trobe University Press, $36.99 pb, 320 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781760645755/looking-for-elizabeth--helen-trinca--2025--9781760645755#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

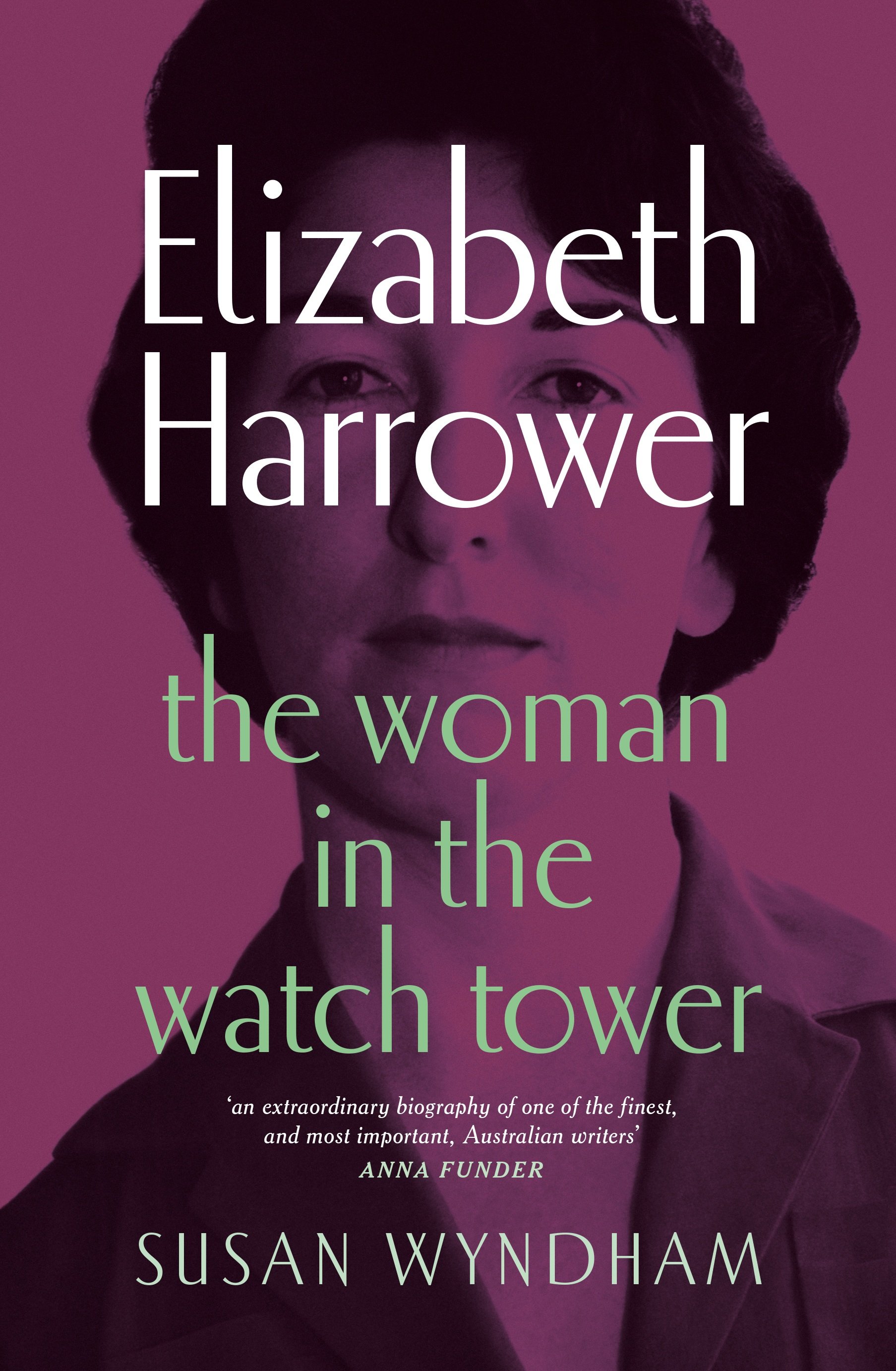

- Book 2 Title: Elizabeth Harrower

- Book 2 Subtitle: The woman in the watch tower

- Book 2 Biblio: NewSouth, $39.99 pb 336 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781761170195/elizabeth-harrower--susan-wyndham--2025--9781761170195#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

How to do them justice? Reading one through might make the second one feel stale. I tried reading them chapter by chapter, turn and turnabout, but that became confusing. I decided to read them in their order of publication: first come, first served. First Trinca, then Wyndham.

The Elizabeth Harrower story can be a seductive braid of two compelling tropes. The first is a Cinderella mash-up with Sleeping Beauty, where Betty Harrower, the Newcastle born daughter of a young, unhappily married couple, is first left to the predations of her awful grandmother and then taken to Sydney by her mother who had remarried a wealthy but dubious man. Richard Kempley became Betty’s despicable, narcissistic stepfather, lifting her and her mother up from provincial Newcastle to a life of money and travel, while oppressing her mother in a prison of manipulation.

In so doing, Kempley endowed Betty with much to write about as she became Elizabeth Harrower, author of four original and compelling novels published in the late 1950s and the 1960s. After failing to win the 1967 Miles Franklin Award for The Watch Tower (1966), her fourth and most compelling novel, she fell into a mid-life fallow period from which, despite her reported efforts, no new novels emerged.

In her eighties she was visited by a literary prince charming in the form of Text Publisher Michael Heyward, who republished her mid-century novels and brought her to an enthusiastic new readership through the Text Classics series. Harrower was celebrated for her astute psychological reading of the human condition, and widely interviewed, mostly declining to give away too many personal details.

After a while she allowed Heyward to read a long-hidden manuscript, In Certain Circles, a book likely written in the late 1960s that was not embraced by her British publisher, and that she had withdrawn from publication in 1971. Heyward published it, giving her the chance to finally win the prizes that she was denied in her first blooming, even though the novel was not nearly as strong as her earlier ones. Elizabeth Harrower enjoyed her second coming; she loved the book signings and public interviews, and then, as many older people do, succumbed to frailty and dementia, and died.

The other story you will find on Netflix and in Scandinavian noir crime narratives. The crime here is the author succumbing to writer’s block. What made Harrower stop writing novels after her mid-life wave of success? Why was she so private? What secret was she hiding? Is it a literary crime not to write? And if so, who is the criminal responsible? Who murdered her career?

We are used to the literary romance story of the writer who sacrifices all for the work, whose commitment to the gods of inspiration far outweighs any interests in home and family, friends and love. Here, no matter if you are a mean alcoholic or a cruel bastard, you are admired from afar and allowed the choice of keeping on writing or dying young. Harrower was guilty of not continuing her writing and dying old.

And what of a life, outside of the writing, that was lived well? What value is there in this?

Trinca opens Looking for Elizabeth: The life of Elizabeth Harrower with the night of the 2015 Prime Minister’s Literary Awards when Harrower’s fifth novel, In Certain Circles (2014), was shortlisted in the fiction category. Having never quite recovered from missing out on the 1967 Miles Franklin, she is once again disappointed, and the eighty-seven-year-old Harrower catches a cab home alone. It is a poignant account of hopes dashed, again. Trinca then unfolds Harrower’s life from her Newcastle beginnings to her life in London and again in Sydney, and her rediscovery by the Australian literary community, long after all those who knew her in her heyday, and remembered her achievements, had died.

But there is another story woven through the life of Harrower which came as a surprise to me – Trinca repeatedly implies that Harrower was a closet lesbian, who had crushes on a string of older women throughout her life: her boss in a clothing factory, her older cousin Margaret Dick, her friend Kylie Tennant, and possibly others. Her cousin? With whom she shared digs in London and later in Sydney? Tennant, who was married with kids? She did buy a writing shack with Tennant, but did this make them a couple? Call me out as an unsophisticated, straight grandmother, but I met Harrower a couple of times and it was my impression that she was a woman who liked men; she was borderline flirtatious and crazy about Michael Heyward. I wonder what she’d make of Trinca’s conjecture. She might have been more surprised about this than about having inspired two biographies.

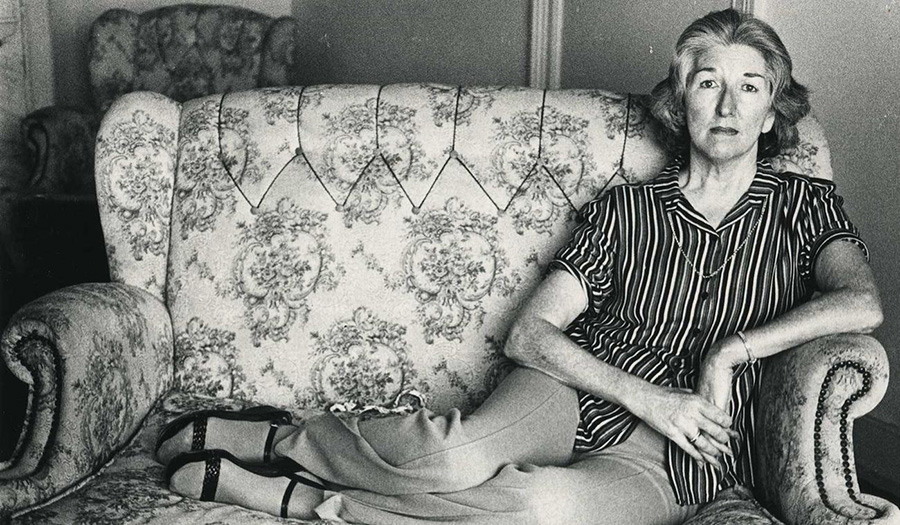

Elizabeth Harrower (Text Publishing)

Elizabeth Harrower (Text Publishing)

Trinca speculates that Harrower’s friendship with Kylie Tennant railroaded the writer from getting her work done. As did her care for Shirley Hazzard’s difficult mother, which took place while the New York-based Hazzard was writing her own books far from her mother in Sydney. Harrower might have been a bit of a handmaiden to these people, but maybe she was gathering her observations about human psychology.

Trinca seems keen to solve the murder of Harrower’s writing career and settles on Harrower’s friend Patrick White as the culprit. Somehow his encouragement of her writing, his insistence that she did not waste time on ‘vampires’, who he thought unfairly demanded her attention, is portrayed as driving Harrower’s resistance to his encouragement, an incentive to – perversely – do the opposite and not foreground her work: to cut off her nose to spite her face.

In Wyndham’s book, Elizabeth Harrower: The woman in the watch tower, I found the compelling presence of a different Elizabeth Harrower.

Like her subject, Wyndham locates herself as a childless writer, the only child of divorced parents. Her more detailed research sets the reader inside the Newcastle story, Harrower’s schooling, her father’s distance, her relationships with her beloved mother and her cousin Margaret. On the lesbian business she writes: ‘Invitations were often for Elizabeth and Margaret. People who saw them together wondered about their relationship, some assumed they were a couple, but those that knew them well understood their familial symbiosis.’

In Wyndham’s reading, Harrower’s devotion to a range of friends, and relatives of friends, may have served as a source of material for books, an arena for her to give and receive kindness, or even an excuse for procrastination. One might say that she was drawn to rescue older women as she felt compelled to do with her own mother.

It is possible that her reluctance to spill the beans about her life arose from a certain mid-century attitude about the value of writing from the life rather than from the imagination – she might have been ashamed that her early years had fuelled her, and that she did not experience the same impetus in her more comfortable middle years. Autofiction had not yet emerged as a respectable creative framework. Writing was more about being creative, about being touched by the gods. As Wyndham writes of Harrower:

Looking back from old age, on the decision to withdraw In Certain Circles and all that followed, she said, ‘That’s when I decided to destroy my life.’

In this book Harrower is not a closet lesbian who was bullied into not writing by her friendship with the difficult Patrick White but a woman who had a gift for friendship, who set high standards for her writing, and who perhaps recognised a creative slackening in her middle years.

In Trinca’s account of her interview with David Malouf, she says that Malouf thought that while White’s opinion mattered to her, Harrower was comfortable drawing a line under her novels, and that ‘at that time she couldn’t see that anything she wrote would amplify them in any way ... she thought not, and I had huge respect for that.’

So, whodunit? Elizabeth did. She wrote what she had to, and then she went on to live well, read, have dinner parties, see plays, travel, and enjoy the pleasures of friendship and kindness, all the ups and downs that these things entail, and to see a new generation of readers appreciate what she had to say about people and life and love. No crime in that.

Comments powered by CComment