- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Barely noticed

- Article Subtitle: A new account of Australian families

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

We have had histories of Australian motherhood for decades. Fathers feature – sometimes as villains – in some of our best loved fiction: D’Arcy Niland’s The Shiralee (1955), George Johnston’s My Brother Jack (1964), and Don Charlwood’s All the Green Year (1965) spring to mind. Rounded portraits of fathers have figured in memoir and autobiography. Examples by Germaine Greer, Manning Clark, Raimond Gaita, and Biff Ward stand out. But not so in works of history, where there is a strange silence.

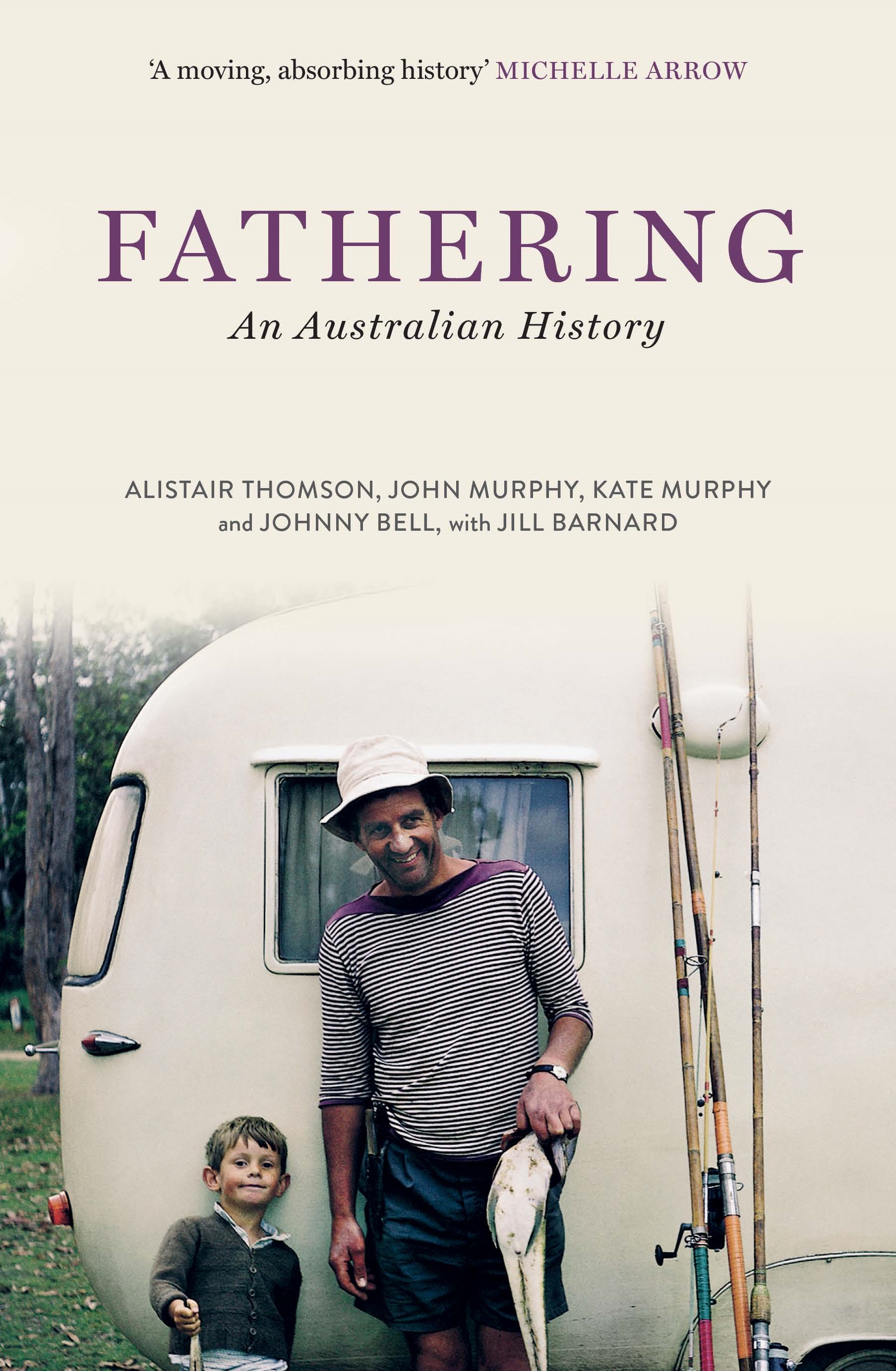

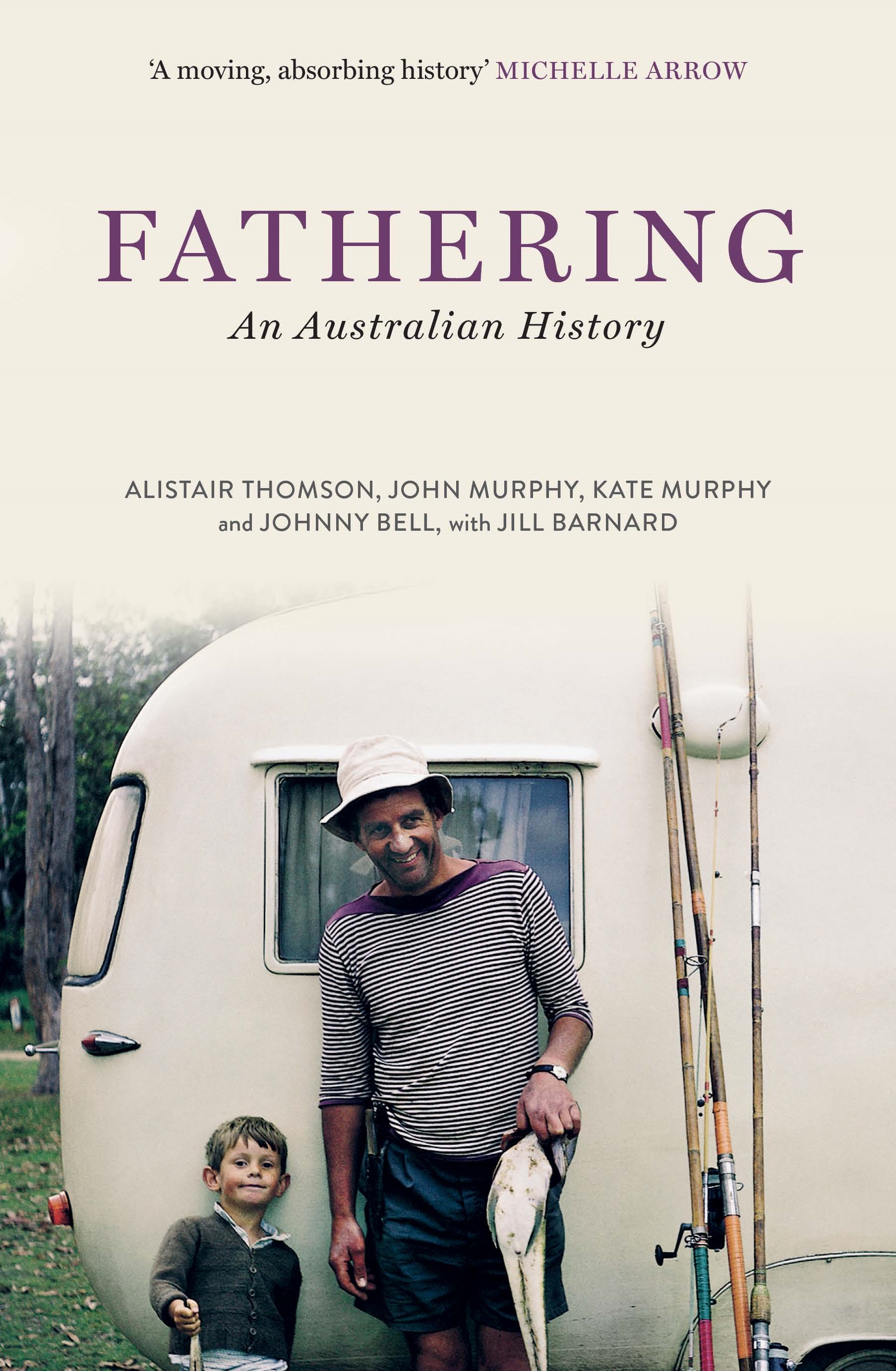

- Book 1 Title: Fathering

- Book 1 Subtitle: An Australian history

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $39.99 pb, 432 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780522881257/fathering--alistair-thomson--2025--9780522881257#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

The absence of fatherhood from historical scholarship might echo the phenomenon of the absent father himself. If fathers have been invisible to historians, or at least less visible than mothers and children, it might be in part because they made themselves scarce. They threw themselves into their work. They headed off to the pub for the night. Or maybe, like a number mentioned in Fathering: An Australian history, they just headed off for good, preferring an unencumbered life. But Fathering also shows that the supposed retreat of men from domesticity in favour of the cult of mateship has only ever been part of the story of Australian family life.

Husbands and fathers were there for their children. Even if they were not being demonstrative, they might still show their love for their children in quiet, subtle ways. Breadwinning itself could be an act of ‘affective care’. The image from the book that stands out for me is a simple but moving one: an unskilled labouring man walks with his children each week to a library, showing his love for them by opening up the wider world of literacy and learning.

The book’s title, its team of Melbourne-based authors explain, is Fathering, not Fatherhood. Their focus is on ‘the lived experience of fathers’, not what people said about it – although there is, in fact, plenty of the latter too. Fathering relies heavily on several major oral history projects undertaken since the 1980s rather than on fresh interviews. (Alistair Thomson, John Murphy, and Jill Barnard, three of the book’s authors, were involved in some of this earlier work.) Interviews that were often conducted with other purposes in view, or at least not designed specifically to explore fathering, are reworked for what they might reveal, like the tailings of an abandoned gold mine. That has clearly involved frustrations for the researchers – inevitably earlier interviewers did not always ask the ‘right’ questions – but the tailings happen to be quite rich once considered together and they are supplemented by a diverse range of other materials. Chapters alternate between biographical ‘portraits’ of individuals and families and broader studies of the major trends and themes of the period under review. The book begins in the interwar years and ends in the recent past and present; the world of the children’s television show Bluey and Covid-19.

The result is a richly textured study that occasionally threatens to overwhelm us with its detail. It is also written accessibly and lightened by frequent quotation from interview material. The informants themselves are ‘historians’ in the democratic, demotic sense, narrating and interpreting their own lives but also the times through which they lived. Jake Ewing, a Hunter Valley man, comments that ‘the world we were educated for in the 1970s didn’t exist in the late eighties, disappeared in the 1990s’. Quibble if you like, but I’m with Jake.

The authors are struck by some powerful continuities, too, even as so many aspects of Australian society changed utterly. Intergenerational relationships matter. Sons emulate the best of, or seek to avoid the errors of, their fathers. My own father, born in the Wimmera in 1923, told me of his father, an Italian-born country-town businessman, giving him the occasional ‘hiding’ with a ‘razor strop’. (I didn’t know what a razor strop was but it sounded nasty.) My father, who used an electric razor, never laid a hand on me.

By mid-century, there was talk of ‘new fathers’ who were less authoritarian and more engaged with the lives of their children. Boomers rejected the patriarchal and distant fathering they had sometimes experienced but nonetheless found themselves working late more often than they wanted, complaining that the kids were asleep when they left for work and when they came home. Gen Xers might have resolved to spend less time at work and more at home, but the economy imposed its own limitations. Millennial dads talked of taking an equal share of the parenting but found themselves working long and irregular hours to build careers and pay off large mortgages. Each generation of fathers seemingly resolves that it will be more involved in the lives of their children than the one before. Yet, class and economics intervene, and ideas of the natural role of mothers as primary carers are resilient. Modern dads do invest time in caring for their children, though research suggests they tend to do ‘the fun stuff’.

The ideal of the male breadwinner has exercised a powerful influence across generations, even as mothers entered the workforce in greater numbers. Australia was hardly alone in this. The authors point out, however, that Australia was distinctive in embodying the idea so securely in public policy via the family wage. Unequal pay, tax incentives, and a lack of childcare reinforced the idea that men go out to work and women stay home. A cultural stigma on husbands ‘allowing’ their wives to work also did some heavy lifting. Even as the new feminism of the 1970s prompted reconsideration of gender roles, mothers were still seen as better suited to the more active, present, and hands-on part of raising children, especially in their early years.

The authors point out that the lived reality of the male breadwinner system was rather brief: it lasted for about a generation, during the ‘prosperous times’ between about 1950 and 1972. Depression and war ensured that it was more ideal than reality for large numbers of Australians in the first half of the century. The end of the long boom in the mid-1970s, combined with rising workforce participation of married women and the emergence of solo parenting, eroded the system thereafter. Fathering changed against this background, shifting towards nurturing and away a little from providing – but only a little. Feminism exercised its own influence, changing ideas about fathering, yet there was also a backlash politics that saw the emergence of the ‘angry father’ as media type and campaigning activist.

Bluey © Australian Broadcasting Corporation (TCD/Prod.DB/Alamy)

Bluey © Australian Broadcasting Corporation (TCD/Prod.DB/Alamy)The authors are alert to the distinctive experiences of Indigenous people, as well as of non-Anglo-Celtic migrants. The authorities who created the Stolen Generations paid little attention to the extended kinship networks that facilitated fathering (as well as mothering and other forms of guardianship) for Indigenous children. Migrant families brought their own expectations about what fathering might entail. Some preserved the authority of the father as ruler of the home and provider for the family with great strictness. There were also migrant groups in which married women commonly worked.

The sheer diversity of fathering in Australia makes this kind of social history a hard act to pull off. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that things are just very complicated and that fathering was diverse. Still, the authors do well in assessing the impact of changing material, ideological, and cultural forces in sustaining and reshaping Australian fathering. This impressive study will complicate and enrich existing understandings of gender relations, family life, and masculinity. Most valuably, it should provoke deeper reflection about our own fathers, and our own fathering – figures and acts that we might have almost forgotten, or barely even noticed in the first place.

Comments powered by CComment