- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: ‘A magabala seed: Lilly Brown and the next 10,000 years of an Indigenous press’

- Review Article: No

- Article Title: A magabala seed

- Article Subtitle: Lilly Brown and the next 10,000 years of an Indigenous press

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Located on Yawuru Country in Rubibi (Broome), Magabala Books is one of the most remote publishers in the world. This First Nations publishing house has helped redefine Australian publishing since the 1980s by continually ensuring that Aboriginal stories and voices are in print. Since its formal establishment in 1987 – following a landmark desert meeting in 1984 and with funding from the Australian Bicentenary Authority’s National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Program and the Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Cultural Centre – Magabala has published more than 250 authors from across Australia. The press emerged in direct response to the widespread appropriation of Indigenous stories by Settler people and publishing houses and continues to define how publishing can best serve Aboriginal authors, artists, and illustrators.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

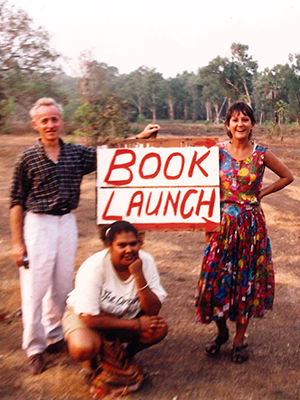

- Article Hero Image Caption: Peter Bibby, Merrilee Lands, and June Oscar heading to a Magabala book launch, 1990 (courtesy of Magabala Books)

Magabala Books is not discreet about its ambitions. Its logo depicts a magabala – a bush banana – stylised with its seeds spurting from one end, situated above the press’s motto: ‘Changing the world, one story at a time’. Merrilee Lands, the press’s first author and first trainee Aboriginal editor, explains why the Aboriginal board chose the magabala fruit for the name of its press: ‘When the fruit dries up, it splits, and the seeds fly off and stick onto other trees and that’s where it grows.’ Lands explains that the magabala is like ‘our culture dispersing across the land and engraining itself in someone’s mind’. Many of Magabala’s early publications, such as Bill Neidjie’s Story About Feeling (1989) and David Mowaljarlai’s Yorro Yorro: Everything standing up alive (1993), are now staples of the Australian school curriculum and taught in Australian and First Nations tertiary literary subjects around the world. The commercial success of Kirli Saunders’Bindi (2020) and Bruce Pascoe’s controversial Dark Emu (2014) has redefined the place of First Nations authors in the fields of adult fiction and history and established a permanent place for First Nations voices in Australian bookshops. Since its inception, the press has been committed to children’s publishing, which for Magabala includes works written specifically for children, such as Sally Morgan’s Welcome, child! (2021), and works by children: Cowboy Frog (2003), written and illustrated by Hylton Laurel when he was nine years old, is among Magabala’s long list of bilingual children’s literature. In addition to publishing First Nations authors, Magabala has upheld a commitment to the indigenisation of publishing, which has primarily meant the training of Aboriginal editors and publishers. Further developing this project, Magabala has just appointed an Aboriginal CEO for the first time: Gumbaynggirr woman Dr Lilly Brown.

Magabala’s bookshop and offices are housed in a modest building perched next to a large boab tree on Bagot Street. From Magabala’s front door it is possible to see the red dirt of the Kimberley and the blue of the Indian Ocean. Brown comes out to the bookshop to greet me dressed in a yellow T-shirt with a graphic print of an Aboriginal flag neatly tucked into trousers and a pair of casual heels. As we walk through the office, she checks in with staff members and asks about their weekends and what is trending on the internet. She pays her respects to Edie Wright, a Director of Magabala’s board, and to Magabala’s former CEO, Anna Multon, who have dropped in for a cup of tea.

Brown’s arrival at Magabala Books has been a long time coming. Anita Heiss’s Dhuuluu-Yala: To talk straight, the landmark 2003 study on Aboriginal publishing and editing, explored Aboriginal critiques of and frustrations at Aboriginal publishing houses being staffed by Settlers. Heiss quotes at length from Blanche Bowles, a trainee manager at Magabala in the 1990s. In a 1994 government report on Aboriginal culture, Bowles explained that the organisation must be filled with Aboriginal people to guarantee that the organisation achieves economic independence.Moreover, she claimed that the staff’s familial and communal ties would be vital to ensuring that ‘culturally appropriate nests of material’ were submitted to and published by the press. While Settler people have long managed Aboriginal organisations, Magabala’s founders understood this as an intermediary step towards the creation of an Indigenous organisation.

Being a ‘first’ is not new for Brown. She was the first Aboriginal graduate of the University of Cambridge, where she completed a Masters of Philosophy in Politics at Trinity College. After being offered a place for her doctorate at both Oxford and Cambridge, she returned to Naarm (Melbourne) to earn her PhD at the University of Melbourne. Then, in 2021, she became the first Indigenous executive director of the youth-focused mental health foundation Headspace. Brown and I did our honours year together at the University of Melbourne. Her early interest in language revitalisation in Kim Scott’s writing stuck in my mind. Language revitalisation is now a defining feature of First Nations literatures, and First Nations languages are increasingly taught in Australian schools as they appear in society more broadly.

Brown gathers the office and visitors around the table for morning tea and starts pulling espressos for everyone on the new coffee machine. As Brown passes a cup of coffee to Multon, the former CEO remarks that Magabala used to be known for its loose-leaf tea. Brown acknowledges Multon’s role in Magabala being named Small Publisher of the Year at the Australian Book Industry Awards for the second time in five years. Around the table there is talk of ‘bara’ or barramundi in the creek and I am warned to avoid the frog in the toilet. Wright, who is also a Magabala author, describes her long career in Aboriginal and Settler educational spaces: ‘I used to work in literacy; now, I work in literature.’ ‘Literacy’ is often framed as a deficit model for thinking about First Nations children and people, and ‘literature’ is a name for the storytelling that has always been happening here.

As everyone heads back to their desks, I ask Brown about her move from working in mental health to publishing, and she paints a broader picture of both herself and the seemingly disparate industries in which she has worked: ‘Actually, I went from lecturing in a university to working in mental health and now in publishing but, before that, my training was in Indigenous Studies, anthropology, and history. While working in all of these sectors, I have been motivated by the question: What does intergenerational healing mean? What does that look like in practice? I must have been one of the only executives in mental health advocating for the role of books and television in healing.’

‘Ultimately, a CEO has a skillset – one that can be learned,’ she says as she gestures to her junior Aboriginal staff members: ‘I give them five years.’ Brown may no longer be working in the university sector, but it is clear that Magabala is a training ground for First Nations editors, publishers, and CEOs. While a CEO’s skillset might be transferable between industries, Brown stresses that running Magabala Books is different from working at a Settler institution: ‘ninety-nine per cent of my work in every other organisation now takes up one per cent of my time. I loved my other jobs, but it was mainly having to fight to support the people around me and rationalise to everyone else why what we are doing is important.’ She looks at me with a smile. ‘Whereas what we’re doing here is operationalising thousands of generations of Blak brilliance.’

‘But it’s not about me, Ruby,’ she says as we walk into her office, which is lined by bookcases containing every edition of every book that Magabala has published. My eyes run over copies of works by Jack Davis, Ali Cobby Eckermann, and Elfie Shiosaki. Brown points up at the wall above her desk, on which hangs a framed picture of two Elders and founders of Magabala, Violet and George Jormary, sitting on a rock and looking straight at the camera. ‘This is all foreseen. It’s what these old fellas were like. They knew what they were doing.’

Magabala Books was conceived during a historic meeting in the bush in 1984. Meeting at a cultural festival held at Ngumpan, members from diverse Aboriginal traditions across the Kimberley determined that they needed to protect not only Aboriginal land but also Aboriginal law, culture, and people. In addition to an Aboriginal land council, legal, and health services being established out of this meeting, the Elders also called for a cultural centre and publishing house to be created in the name of Aboriginal self-determination and futurity. Magabala would not only address the appropriation and misrepresentation of Aboriginal stories and storytellers in mainstream publishing but also serve as a means of enacting rights over culture and sovereignty.

Settler Australians and our organisations can be prone to thinking in rather small durations. This is perhaps best comprehended in the gap between the ubiquity of the five-year plan, favoured by governments and policy makers, and the Yugambeh Kombu-merri and Waka Waka philosopher Dr Mary Graham’s assessment that we need planning for the next 10,000 years of culture. I ask Brown about her vision for Magabala and she replies: ‘In 10,000 years we want our children to be who they want to be. We want our communities to be who they want to be and for Magabala’s titles to reflect that. Of course, there are operational questions that I am working on, but the future of Magabala is continuity.’

Brown explains that Magabala invests in stories ‘that need to be published’ rather than those that turn a profit. ‘I am lucky – as the CEO – that there have been very hardworking non-Indigenous folks that have got us government grants which are linked to our core purpose. This is not where the majority of our money comes from. We sell books. Works such as Dark Emu and Bindi have been a large source of income.’ Brown claims that this is a balancing act: ‘In order to publish more Blak titles, we need to release First Nations stories that appeal to Settler readers.’ Brown pauses and says, ‘We also receive Blak philanthropy.’

Dr Lilly Brown, Kirli Saunders, and Dr Elfie Shiosaki in conversation at Corrugated Lines: A Festival of Words, 2021 (photograph by Matthew Adams, courtesy of Magabala Books)

Dr Lilly Brown, Kirli Saunders, and Dr Elfie Shiosaki in conversation at Corrugated Lines: A Festival of Words, 2021 (photograph by Matthew Adams, courtesy of Magabala Books)

While First Nations titles have come and gone from the shelves of mainstream booksellers in Australia since the 1980s, the last decade has seen an exponential rise in the demand for First Nations books. Brown explains, ‘I’ve been having conversations with publishers on the East Coast, and I asked Dymocks when they started stocking all these Blak stories. Dark Emu was the turning point for them. Since then, they have been looking for new works and keeping First Nations books in stock.’ While the commercial demand for First Nations books is relatively new, Magabala has been acting as the custodian of First Nations stories for almost forty years. In contrast, Brown explains, ‘mainstream publishing houses are not publishing First Nations titles for non-commercial reasons.’

With the recent increase in a demand for Indigenous writing, Aboriginal authors are being exploited in new ways. The 1990s saw a number of publishing hoaxes, the most famous examples of which include the Settler American author Marlo Morgan’s Mutant Message Down Under, in which the author fabricated a meeting with Aboriginal people, and the Wanda Koolmatrie affair, in which Leon Carmen and John Bayley went so far as to fabricate the identity of an Aboriginal woman and publish a novel under her name. Brown and I discuss the ongoing Settler desire to appropriate Aboriginal identity and knowledge for profit: ‘Mainstream publishing houses are all of a sudden slipping into people’s DMs and being like, “Can we tell your story?” We hear of authors having ghostwriters and some publishers actually writing the stories for them and then putting their names on it.’ Now, corporations – rather than individual authors – are impersonating Aboriginal people for financial gain and cultural prestige. ‘Magabala exists to serve community,’ Brown says as she sits back in her chair and smiles.

When I get back to Naarm, I decide I need a better way to describe the sunset in Rubibi than my own ‘awe’. I reach for my dog-eared copy of Yorro Yorro: Everything standing up alive. Mowaljarlai explains that ‘Njallara, the colour of the sunset, means the arse of the sun.’ I laugh, and flip through the book, which opens at a page containing the same photograph of Magabala’s Elders that hangs above Brown’s desk. This picture sits within the pages of a story about the sun and her mother – an allegory depicting the stability of female leadership. Mowaljarlai explains that this story is for future generations: ‘In spite of the poisoning of the world,’ future generations will have ‘restoring powers’. It is not only Magabala’s founding board members who are aware of their actions: CEO Lilly Brown knows what she is doing

- I use the word ‘Settler’ not to refer to the first wave of British colonisation in Australia but as a designation for all people of non-Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent living in historical and contemporary Australia. This is a preferable term to ‘white’ because the distinctions between First Nations and Settler people are politically and culturally significant but cannot be tied to skin colour. ‘Settler’ is also preferable to non-Aboriginal, which has a seeming neutrality that conceals the ongoing politics of colonisation in Australia.

The ABR Inglis Fellowship – funded through donations – honours the remarkable Ken and Amirah Inglis, whose writings and participation in Australia’s cultural and social life enriched this country. The Inglises were generous in encouraging young writers and providing them with rare opportunities. ABR acknowledges the generosity of those who donated to the Inglis Fellowship. Ruby Lowe is the first ABR Inglis Fellow.

Comments powered by CComment