- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Indigenous Australia

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Ugly legacy

- Article Subtitle: The role of nuclear in colonialism

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Coalition was keen to spruik a nuclear future in Australia’s most recent federal election campaign. Conspicuous in its absence was a reckoning with Australia’s nuclear past. In Contaminated Country: Nuclear colonialism and Aboriginal resistance in Australia, environmental historian Jessica Urwin rightly puts that ugly legacy back in our minds.

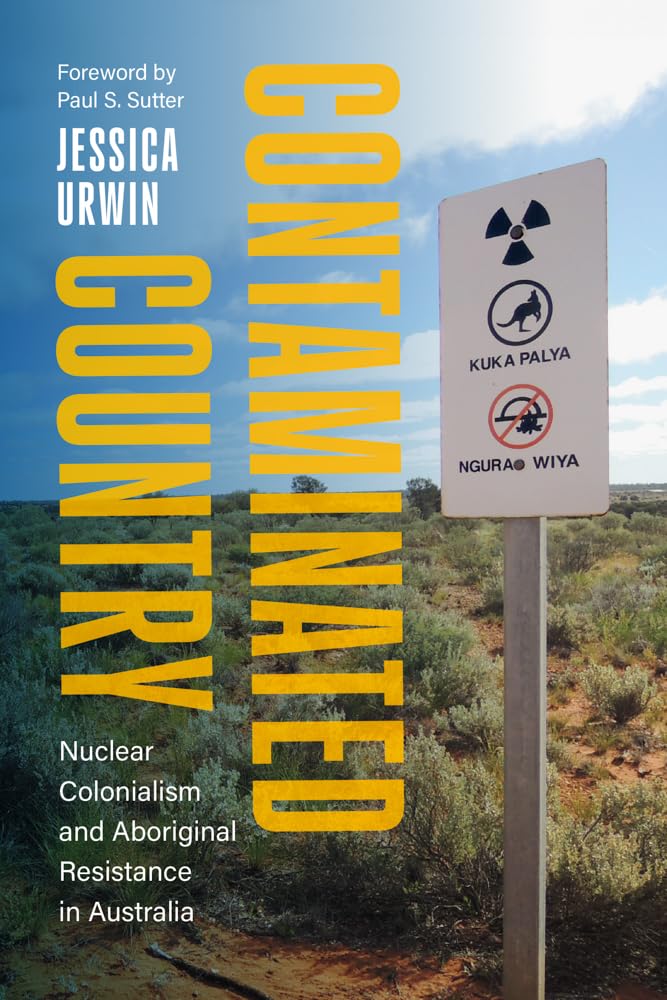

- Book 1 Title: Contaminated Country

- Book 1 Subtitle: Nuclear colonialism and Aboriginal resistance in Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Washington Press, US$110 hb, 296 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Casting a critical eye over uranium mining, nuclear weapons testing and waste management in Australia, and with a focus on rural and remote South Australia, Contaminated Country tells a history of settler colonialism through the development of nuclear science and weapons testing. Other studies in this field – particularly those taking in the US context – utilise the concept of nuclear colonialism to explain how the worst effects of uranium mining, weapons testing, and waste disposal tend to be disproportionately experienced by Indigenous peoples. Bringing further nuance to this concept, Urwin shows firstly how nuclear colonialism’s effects in Australia were felt long before World War II ushered in a new nuclear order. Secondly, through extensive interviews and a careful reappraisal of the documentary evidence, Contaminated Country reveals Aboriginal people as key players in Australia’s nuclear past, actively resisting and reshaping the ways in which those different historical forms of nuclear colonialism evolved on their Country.

Australia was, as Urwin reminds us, ‘one of the only independent countries in the world to have offered up its sovereign lands for the testing of another state’s nuclear weapons’. Yet whereas this might lead the reader to see Australia as a victim of the new nuclear order, Urwin’s key contribution is to show that Australia was in fact a perpetrator of nuclear colonialism. Throughout the book, Urwin reflects on three distinct ways in which Australia disrupted and dispossessed First Peoples in its pursuit of nuclear energy: through mining, weapons testing, and long-term storage and de-contamination efforts. During the twentieth century, nuclear colonialism was the latest means through which imperial states, including Australia, could flex their muscles.

Urwin opens by critically re-examining the role played by Douglas Mawson (better known for his exploratory work on a different kind of frontier, that of Antarctica) as a booster of mineral exploitation in South Australia. When it was discovered that South Australia hosted little gold, Mawson envisioned it as a centre for the mining of radium and uranium. In Urwin’s analysis, mining is explained as a ‘colonial contradiction, involving the dual elision of and reliance on Aboriginal people’ through their labour. In this way, decades before the period of nuclear proliferation that was a hallmark of the Cold War, a pattern of mineral exploitation and settler violence was already taking shape in the Australian context.

Contaminated Country revisits nuclear weapons testing in South Australia and makes a number of key scholarly interventions. Whereas the Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia (1984–1985) highlighted the role of former Prime Minister Robert Menzies, finding that ‘the original decision to lend Australia to the United Kingdom for the purpose of the latter’s nuclear tests program was taken by Australian Prime Minister Menzies without reference to his Cabinet’, Urwin argues that Labor under Bob Hawke also carried on a legacy of nuclear colonialism, following his apparent ‘support of the soon-to-be Ranger [uranium] mine’. We also see here the diverse ways in which First Nations people affected by the weapons testing wielded considerable political clout, meeting with similarly impacted communities in the Pacific, including those living on and near Bikini Atoll which was subjected to US nuclear tests from 1946.

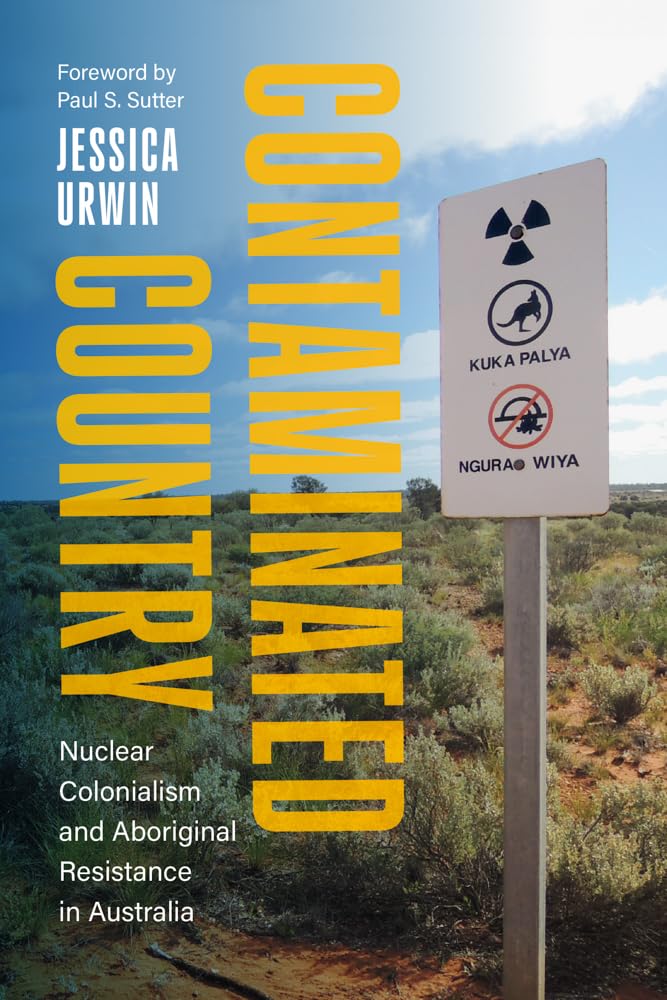

Galarrwuy Yunupingu at the opening of Ranger Uranium Mine, 1979 (Library & Archives NT via Wikimedia Commons)

Galarrwuy Yunupingu at the opening of Ranger Uranium Mine, 1979 (Library & Archives NT via Wikimedia Commons)

Urwin also highlights the key networks that the survivor activists, including the Kupa Piti Kungka Tjuta (a council of Coober Pedy senior Aboriginal women), built during their campaigns to have their contaminated Country cleaned. Testing of contaminated areas was ‘radical’, Urwin explains, because it took seriously Indigenous epistemologies, including those of the Kupa Piti Kungka Tjuta, which required that the poison be left in the ground. Contaminated Country ‘serves as a reminder that nuclear colonialism has not been and is not merely enacted upon peoples, but has been and continues to be challenged, resisted, and forced to adapt’.

Urwin returns to the concept of nuclear colonialism for its explanatory powers, noting that it addresses a form of power ‘predicated on settlers’ long-held assumption that land was, and continues to be, there for the taking’. Whereas scholars have mostly grappled with the environmental injustices wrought by nuclear weapons and nuclear power in the context of Cold War geopolitics, Contaminated Country traces the much deeper roots of environmental racism, revealing it to be a continuation of the settler colonial process. Urwin’s study is built on impressive archival work and interviews, and this material demonstrates at every turn the manifold ways in which nuclear colonialism was resisted on the ground and how scientists, miners, and politicians were forced to adapt. ‘Where in the early twentieth century Aboriginal peoples were actively rendered invisible by the state in the pursuit of nuclear development – irradiated, dispossessed, and silenced – by the century’s end they were active citizens of the nation, agitating for recognition and advocating for Country.’

In 1973, opposition to French nuclear tests in the Pacific was so strong in Australia that Prime Minister Gough Whitlam took France to the International Court of Justice. Friends of the Earth, the Australian Conservation Foundation, and a robust conglomeration of labour unions, including the Australian Bank Officials Association, the Professional Radio Employees Institute, and the Amalgamated Postal Workers Union, united in enforcing a ban on French goods and services, which took effect in May 1973 and coincided with the court action.

But it was principally through Indigenous activism, such as that of Yankunytjatjara woman Karina Lester and the Kupa Piti Kungka Tjuta, that Australia’s own legacy of weapons testing was brought to the attention of the Australian public and connected with the French tests. Urwin deploys what Australian historian Heather Goodall has called ‘official forgetting’ of nuclear testing in remote Australia to explain a culture of prevaricating and obfuscating that lingered for decades after the weapons testing, muddying the waters for historians. More troublingly, until a federal inquiry into the tests was launched in 1984, ‘the experience of [the] unexplained black mist haunted many’. That black mist followed weapons tests at Emu Field and caused illness, including blindness, among those living on Country who were exposed to it.

Contaminated Country is Jessica Urwin’s first book, based on research she conducted for a PhD in history at the Australian National University. That thesis was awarded the American Society for Environmental History’s prestigious Rachel Carson Prize, which recognises excellence in PhD research in the field of environmental history. In Contaminated Country, Urwin has wrangled considerable historical evidence to narrate a convincing and compelling account of settler colonialism enacted through the medium of uranium mining, nuclear weapons testing, and botched de-contamination processes. Hers is a timely and highly instructive study.

Comments powered by CComment