- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Indigenous Australia

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Ladies, Gents, Natives’

- Article Subtitle: A study of local segregation

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

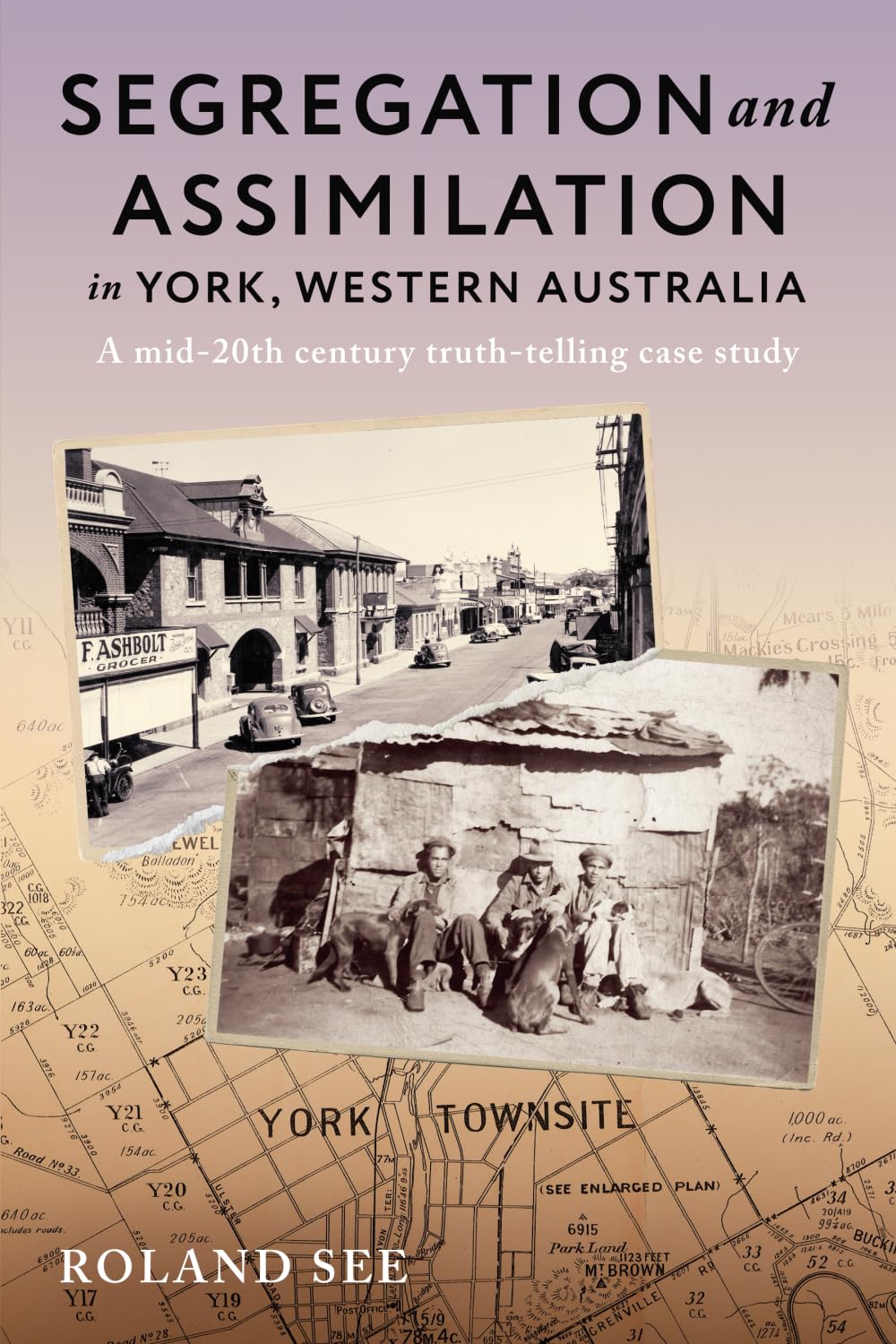

Many Australians are unaware of the extent and severity of formalised racial segregation in the country prior to the 1967 referendum. In this meticulously researched study, Roland See examines the evolution of segregation and assimilation practices in the Western Australian wheatbelt town of York between 1924 – when the town’s Aboriginal reserve was first gazetted – and 1974, the year it was formally disestablished. Unlike in South Africa, where apartheid policies were highly centralised, in Western Australia racial segregation was often initiated and enforced at the municipal level. The state’s Aborigines Act, first enacted in 1905 and amended several times in the following decades, provided local governments with broad authority to create ‘native reserves’ and whites-only areas, enforce curfews, and regulate Indigenous people’s access to public amenities and services. Consequently, municipal councillors were particularly sensitive to the prejudices of their white electors. As See points out, although it was state legislation that enabled racial segregation and persecution of Aboriginal communities, ‘the local position was often the deciding factor in the implementation of such provisions and inhumane injustices’.

- Book 1 Title: Segregation and Assimilation in York, Western Australia

- Book 1 Subtitle: A mid-twentieth century truth-telling case study

- Book 1 Biblio: Book Reality Experience, $32.95 pb, 367 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

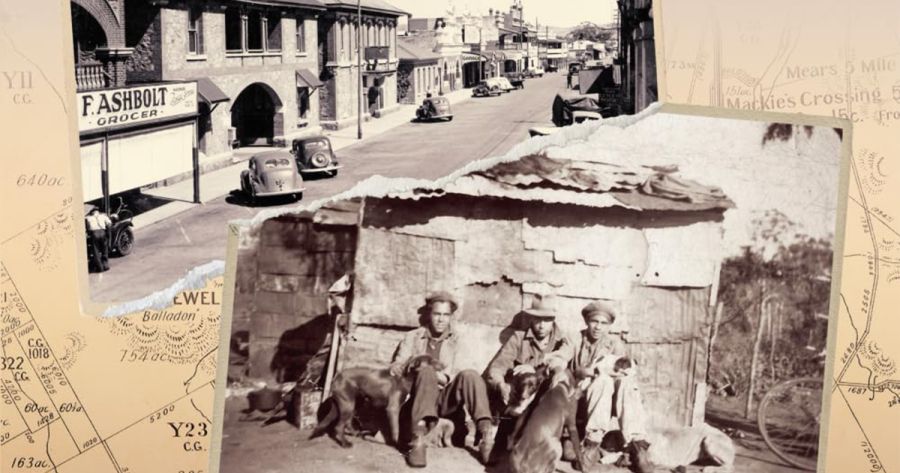

York is situated on Ballardong Noongar country approximately 100 km east of Perth. White pastoralists and farmers had depended upon Aboriginal labour since the violent conquest and settlement of the Avon Valley in the 1830s. This dependence meant most Ballardong continued to live outside the valley’s urban areas. As late as 1930 the town’s newly established reserve was not used as a permanent place of abode and ‘Aboriginal people seemingly did not frequent York in any large numbers’. The situation began to change in the 1930s. A collapse in global wheat and wool prices during the Great Depression ravaged Western Australia’s wheatbelt and as a result many Noongar breadwinners lost their primary means of income in seasonal farm and pastoral work. By 1938 over forty Ballardong people had relocated to York, and late that year the town council for the first time lobbied the state’s Native Affairs department to remove them ‘to a more distant reserve’.

Avon Terrace, York, 1947 (State Library of Western Australia via Wikimedia Commons)

Avon Terrace, York, 1947 (State Library of Western Australia via Wikimedia Commons)

It was in the 1940s that racial segregation reached its zenith in York. The war years coincided with a rise in the number of Ballardong residents, and local officials responded by resorting to increasingly draconian measures. Section 41 of the Native Administration Act (the renamed and amended Aborigines Act) empowered police officers or justices of the peace to order Aboriginal people out of towns and municipal districts if they were deemed to be ‘loitering’. By 1942 a night curfew had been introduced in York, with one police sergeant explaining he ‘had a lot of troubles with natives getting liquor’. In March 1944, Indigenous patrons were banned from attending the town’s cinema, and that same month the town council passed a resolution (later abandoned) to build separate public toilets for ‘Ladies’, ‘Gents’, and ‘Natives’.

Perhaps the most extreme manifestation of these efforts, however, was the adoption of a coerced labour scheme. By late 1941 it had become evident that there was a serious rural labour shortage in Western Australia, largely owing to high levels of military enlistment. The following year, the Department of Native Affairs, in cooperation with the state’s police force, devised a forced labour system whereby ‘all unemployed detribalised Aboriginal people’ would be deported to government settlements such as Moore River for ‘disciplinary treatment’. Afterwards these people would be ‘placed into rural employment under supervision’, and should their conduct be deemed unsatisfactory or they absconded, they would be forcibly returned to the settlement for further ‘disciplinary treatment’. York’s local authorities implemented this system in 1945. Two years later, continuing pressure for racial segregation culminated in the designation of the York townsite as a prohibited area under the Native Administration Act, making it ‘unlawful for natives not in lawful employment to be or remain’ in town without a permit. According to the Native Affairs commissioner, this action had become necessary ‘because of the unsatisfactory behaviour of natives after the hours of sunset’. Their ‘misconduct’ was ‘mostly in relation to liquor, and I am supporting this proposal now because the situation has not improved’.

Just as the town council and electors pushed for total segregation in the 1940s, the state government was beginning to pivot to a new approach to governing Indigenous communities: assimilation. This shift would be resisted by York’s white residents and highlighted the power of local governments to interfere with and delay state policies and directives. One of the first flashpoints was the Natives (Citizenship Rights) Act 1944, which enabled Aboriginal people to apply for and receive citizenship certificates. See emphasises that this legislation in effect only granted limited, conditional citizenship rights. By the early 1950s four of the nine Indigenous people with certificates had been charged and convicted in the York police court: six for drunkenness and one for being at an Aboriginal camp (perversely, certificate holders were ‘deemed to be no longer a native or aborigine’ under the act and prevented from entering these camps). The first half of the 1950s heralded rapid administrative changes at the state level. Conflict soon developed between the Western Australian government’s attempts to force the assimilation of Indigenous people into white society and local municipalities’ determination to maintain the status quo. Unsurprisingly, Aboriginal communities were caught in the middle and in any case the ‘assistance rendered for better living conditions and improved livelihood remained conditional’.

See regards his study as a truth-telling exercise aimed at ‘setting the record straight’ and readily acknowledges that it ‘informs more about settler-Australian society than it does about Aboriginal people’. Be that as it may, his inclusion of letters of complaint to the Native Affairs department, statements in court proceedings, oral history interviews, and other evidence clearly demonstrates that Aboriginal residents of York raised their voices in protest against the inhumane treatment they were subjected to. However, See concludes that this resistance took the form of navigating an oppressive and hostile system rather than actively opposing it. White community attitudes slowly evolved over the course of the 1960s. Charity organisations began to focus on ameliorating the living conditions in the York reserve and over seventy-five per cent of electors voted ‘Yes’ in the 1967 referendum. Although a majority of York’s white residents voted for change, it would be many years before ‘paternalism started to make way for emancipating activism’.

Comments powered by CComment