- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Vietnam

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Path to genocide

- Article Subtitle: A tribunal on war crimes in Vietnam

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

By 1967, the United States was deeply mired in the war in Vietnam. In the immediate aftermath of World War II and until 1954, the Americans had supported French attempts to hold on to their colonial possessions in Indochina. When that failed, they opposed the creation of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, led by the nationalist and communist Ho Chi Minh in the north of the country, and supported the brutal corrupt regimes of Ngo Dinh Diem and subsequent leaders in the south. The United States subscribed to the so-called domino theory that allowing communism to flourish in one Southeast Asian country would inevitably lead adjacent nations to ‘fall over’ into communism.

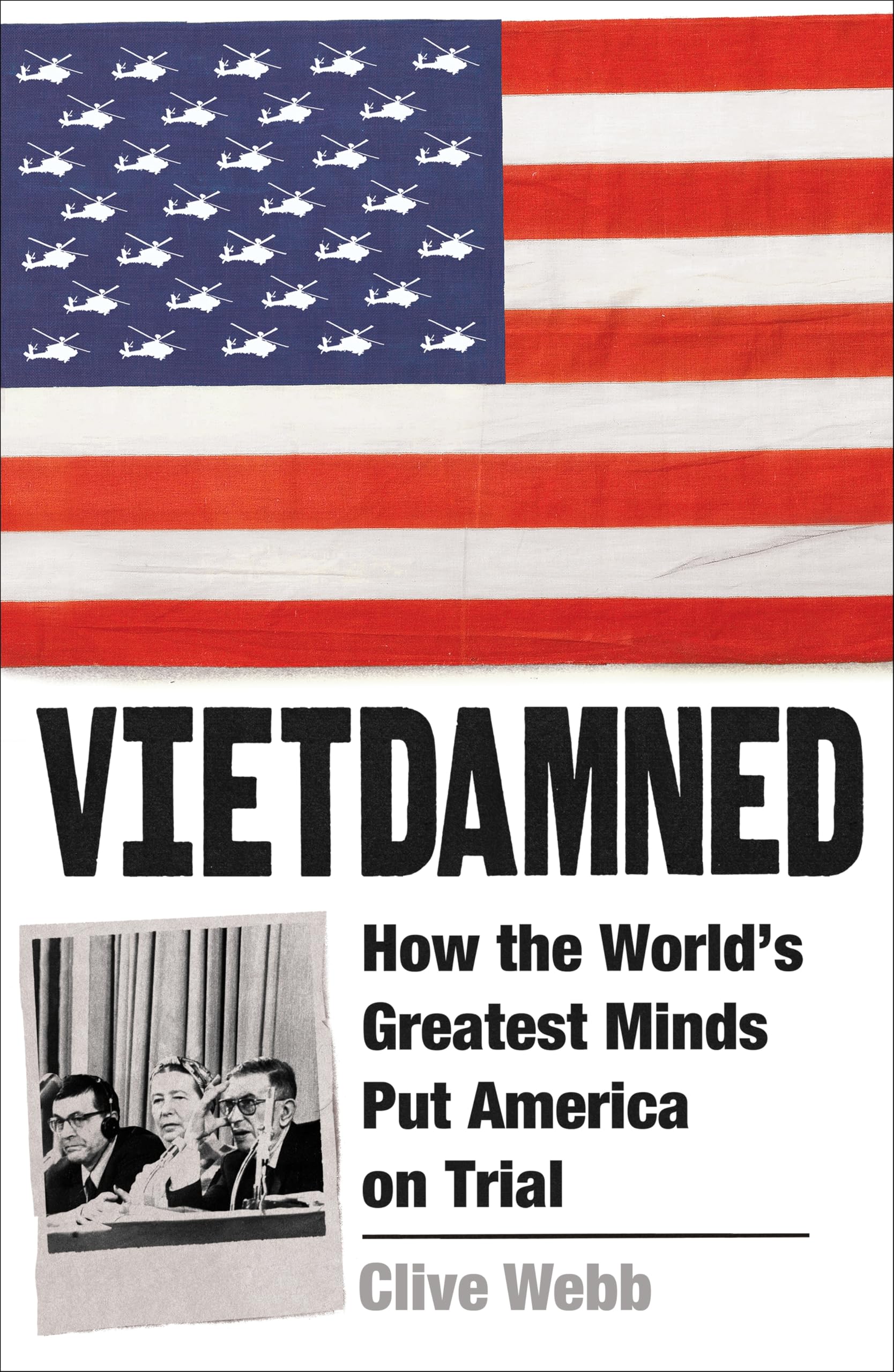

- Book 1 Title: Vietdamned

- Book 1 Subtitle: How the world’s greatest minds put America on trial

- Book 1 Biblio: Profile Books, $45 hb, 320 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781800812338/vietdamned--clive-webb--2025--9781800812338#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

From a thousand ‘advisers’ sent by President John F. Kennedy in 1961, the American presence grew to half a million soldiers on Vietnamese soil by 1967, with 14,000 already killed in action. Australia joined the war effort when Kennedy requested it, in 1962, and in 1965 conscription began; ultimately 60,000 Australians went to Vietnam and 524 died.

In August 1964, a supposed assault on US warships in international waters off the North Vietnamese coast, the Gulf of Tonkin incident, was a pretext for American escalation. However, even with more arms and advisors, the Americans and South Vietnamese were not winning. South Vietnamese forces were inferior to the much more motivated and skilled North Vietnamese fighters, made up of both regular army and National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) guerrillas.

From March 1965, Lyndon B. Johnson – who had become president following Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 – ordered sustained aerial bombardment of North Vietnam that soon extended to the South. Villages, towns, farms, factories, schools, temples, and hospitals were destroyed. In addition to conventional bombing, fragmentation bombs, napalm and white phosphorus would be used, along with biological weapons and spraying of farmlands with potent herbicidal chemicals.

This was a war with no identifiable front, where the enemy could appear suddenly from dense jungle, attack, and just as suddenly disappear. American soldiers who had been told at home that they would be saving the Vietnamese people from communism found that the mostly peasant population largely supported the North Vietnamese fighters, a feeling that grew as more villagers died and had their homes and livelihoods destroyed.

In Vietdamned, British historian Clive Webb does an excellent job of explaining these events. He describes, equally well, the opposition to the war which grew around the world throughout the 1960s, bringing his narrative seamlessly to the establishment in late 1966, by philosopher Bertrand Russell’s Peace Foundation, of a Tribunal on War Crimes in Vietnam. Russell, then aged ninety-five, did not himself attend tribunal sessions but he invited prominent international figures to participate. Many, including Russell and tribunal chairman Jean-Paul Sartre, had opposed previous wars, Russell having served prison time for his opinions. Tribunal members included Simone de Beauvoir, Isaac Deutscher, Tariq Ali, Stokely Carmichael, James Baldwin, Swedish writers Sara Lidman and Peter Weiss, and French lawyer Giselle Halimi, plus scientists, trade unionists, and student activists from several countries.

By 1967, journalists, doctors, scientists, writers, and peace activists who had travelled to Vietnam were speaking out but were rarely published in the mainstream media. There were reliable reports from visitors to both North and South Vietnam of deliberate killings of large numbers of civilians including women and children. Opposition to the war was increasing in the United Kingdom, European countries including France and Sweden, and the United States itself, particularly from students and Black American activists who criticised the unequal burden on Black soldiers in Vietnam.

The opposition coalesced in the decision to establish the tribunal, based on the Nuremberg Trials of Nazi leaders. The aim was simply to determine and publicise what the United States was doing in Vietnam; its findings would have no international legal standing.

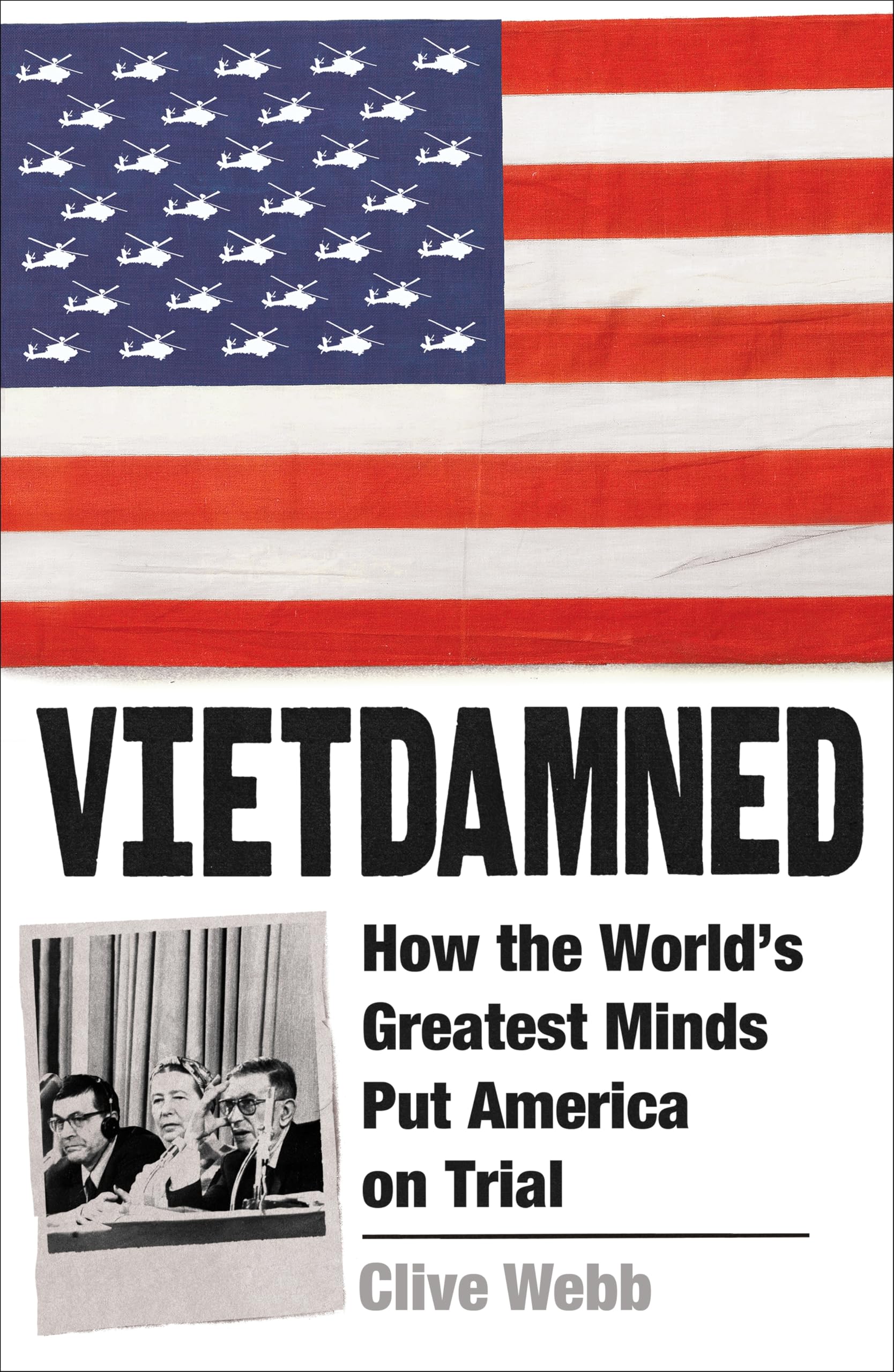

The tribunal’s first session was held in Stockholm in May 1967 and the second in Roskilde, outside Copenhagen, in December that year. Tribunal members sent six research teams including journalists, scientists, and doctors to Vietnam to report firsthand on the situation. Evidence was heard from dozens of witnesses, including North Vietnamese government officials. Particularly chilling was the evidence from Vietnamese victims of aerial bombing and napalm, and from American soldiers who had participated in the carnage.

Jean-Paul Satre, Simone de Beauvoir, and John Takman, Stockholm, 1967 (Svenska Dagbladets bildarkiv via IMS Vintage Photos, via Wikimedia Commons)

Jean-Paul Satre, Simone de Beauvoir, and John Takman, Stockholm, 1967 (Svenska Dagbladets bildarkiv via IMS Vintage Photos, via Wikimedia Commons)

Most of Webb’s book is taken up with detailed and well-referenced accounts of the two sessions, each lasting more than a week. The conclusions from both sessions were overwhelmingly that the intentional slaughter of Vietnamese people was being committed by US soldiers, encouraged by their superior officers, over and above strictly military operational requirements.

Two Australians were at the tribunal sessions. One was the legendary communist journalist and writer Wilfred Burchett, the first Western journalist to enter Hiroshima after the 1945 atomic bombing, a veteran of many wars who had been exiled from Australia by successive Liberal governments refusing him a passport. Burchett was living in Cambodia at the time and was able to reveal details of the hitherto secret US bombing of that country during the Vietnam War.

The other Australian was myself, a twenty-year-old medical student washing floors in Stockholm hospitals to pay for my studies and a supporter of the Swedish anti-Vietnam War committee that was organising the tribunal’s two meetings. I was fluent enough to volunteer to translate, from French, numerous documents presented to tribunal members, the Russell Foundation being cash-strapped.

The enormous volume of evidence produced at the tribunal boosted the anti-war cause, and the tribunal’s structure was replicated in several later inquiries where atrocities were investigated. Some have dismissed the historic significance of the tribunal. Webb, however, argues that it contributed powerfully to ending the war, citing many acknowledgements and accolades. For several years, and before the tribunal wound up in 1975, it helped spark huge demonstrations in London, Paris, and elsewhere, including Australia. Webb does not, however, endorse Sartre’s categorisation of the US actions in Vietnam as genocide.

Late on the tribunal’s last day, I helped translate Sartre’s essay ‘On genocide’, his concluding statement on the tribunal’s findings. While retrospectively events may look different, it must be acknowledged that Sartre was writfing in the middle of the war. His argument was simple: in Nazi Germany, where there was genocide, Jews were killed because they were Jews; in Vietnam, the Vietnamese were killed because they were Vietnamese. It might be said that the path to genocide was being trodden, but that increasing opposition to the war – and the tribunal that Satre himself chaired – helped avert that outcome.

Vietdamned is a well-researched and well-written account of an episode in that terrible ‘forever’ war, one particularly suited to our times.

Comments powered by CComment