- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Reaching Bethlehem

- Article Subtitle: A complex epilogue to an essayist’s life

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

While reading Notes to John I wondered about the words commonly associated with Joan Didion’s style – verve, discipline, precision, breathtaking diction (she is described as capturing the American 1960s and 1970s like no other writer). Notes to John, a posthumous publication of 150 pages made up of notes Didion made following a series of therapy sessions with her psychiatrist, contains clarity and acerbic wit in places, but in general is made up of writing that is dull, repetitive, and achingly private. Didion, who died in 2021, appears to acquiesce to her psychiatrist, Roger McKinnon. His interpretations of her life are often presented as clichéd banalities and Didion tussles linguistically with him without her usual cutting analysis and humour. It is as if in these notes she has given herself over to the supposedly greater power of psychiatric knowledge and in the process become less sagacious. The sessions cover grief, confusion, the indominable wish to understand more about oneself, and how to manage family traumas. But does the writing add anything to Didion’s body of work? I think not.

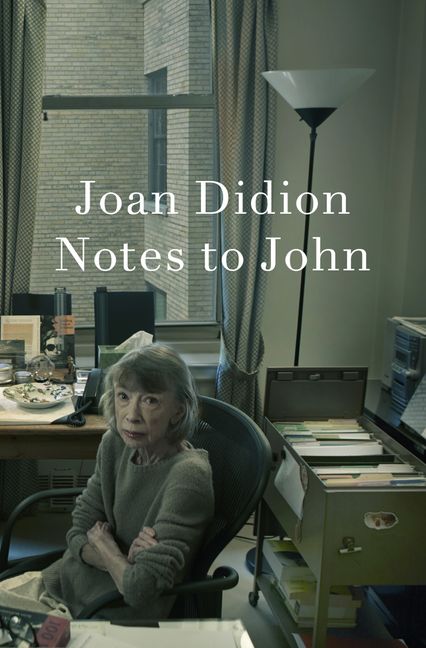

- Book 1 Title: Notes to John

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $17.99 pb, 224 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780008767259/notes-to-john--joan-didion--2025--9780008767259#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Didion’s estate permitted the book to be published after the notes were found among other papers in ‘a small portable file near her desk’. During these meetings, which took place mostly in 2000, she attempts to make sense of her relationship with her adopted daughter, Quintana. The notes are addressed consecutively to her husband, John Gergory Dunne. Whether Didion herself would have published these notes in this format is an ethical yet moot point. Who can know, really? We do know that Didion, as a reporter, diarised copiously most of her life. She once wrote in the essay ‘On Keeping a Notebook’:

But our notebooks give us away, for however dutifully we record what we see around us, the common denominator of all we see is always, transparently, shamelessly, the implacable ‘I’ ... we are talking about something private, about bits of the mind’s string too short to use, an indiscriminate and erratic assemblage with meaning only for its maker.

Notes to John has the characteristics of a case history made up entirely of conversational reportage – its perspective is a subjective one, that of the ‘patient’. We are privy to a lengthy dissection of events, uncertainties, pertinent moments, screen memories. The etiological underpinnings for behaviours are traced back to early childhood and these patterns are thoroughly discussed, as if bringing such memories into consciousness allows the analysand power to change or interrupt repetitive patterns. Because these notes are not typical case history notes, there is an interesting slant on the sessions. Didion recounts that the psychotherapy was Freudian psychoanalysis laced with cognitive behavioural theory but it remains unclear what type of therapy took place. The odd blurring of boundaries between Didion’s own therapist and her daughter’s therapist is particularly disconcerting. In both sessions/ relationships/ therapeutic contexts, the themes of trust seemed predominant and one is left unsure where consent lies. Also disconcerting is the psychiatrist’s ease in sharing homespun anecdotes concerning his own experiences. The psychiatrist is self-revealing in a way therapists are taught not to be: for example, he talks about his own adolescence (‘I did dangerous things’), his own family (‘I grew up in a family like yours’), his own practice ethics (‘I had to make a decision not to treat patients I didn’t want to treat’). Perhaps this is the most interesting aspect of the book. One can’t imagine a psychiatrist saying these things. Perhaps they puzzled Didion, too, though there is no indication of this in the text. Because it is published posthumously, the notation is also less scholarly than is usual for Didon, who was scrupulous in her attention to detail (for example, some poetry quotes are not fully referenced).

The decision to publish was surely not just one for Didion’s estate alone; the book also contains reportage about what the psychiatrist said during these private sessions. Did he have a say in manipulating the text? In reality, psychiatric work is messier, more circumstantial, more marked by resistance and breakthrough, less about giving advice – that fine line, than the picture conveyed by this account. In ‘On Keeping a Notebook’, Didion explained that reality is boring to her; it is filtered reality that interests her – in this case, what interested her was what she might do to dismantle the barriers that impede the wellbeing and autonomy of her daughter.

Stylistically (no doubt to make it clearer who is saying what), the author relies on the phrase ‘I said …’, which begins almost every analysand statement. This marking out of conversational terrain is quite different from Didion’s usually beautiful, complex sentences. It is a testament to the writer’s skill that this repetition doesn’t become more tedious. The writing from beginning to end tantalises even as it explores both the benefits of ‘talking therapy’, the relationship that develops between analysand and analyst, and the shortcomings of counselling, groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous, and other therapies available to those who deal with alcoholism.

What does the book say about Joan Didion the writer? One interesting theme is that a writing career can be a defence against anxiety and depression. A long bow, perhaps, but Notes to John is an extraordinary author portrait, a reckoning with what a writing life has given, and taken. Although Didion perceives herself as an isolate, what emerges from these notes is the entertainer, a person who has established and kept many friends, who has confronted countless media demands, who has met deadlines for films, essays, journals, and novels. And, here, I think of the doped-up children in ‘Slouching Towards Bethlehem’, one of Didion’s most harrowing and perspicacious essays, of the author’s icy observations in which a great empathy for the children lingers. Although less sophisticated than her earlier work, Notes to John seems a fitting epilogue, a final gift, despite lacking the deliciously entertaining and probing aspects of her essays and novels.

Comments powered by CComment