- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Unmask me?

- Article Subtitle: Christopher Hill’s life in history

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The subject of this fine biography was my Doktorvater or postgraduate supervisor. He hailed from York, ancient capital of England’s northern counties. So did my biological father, Wilfred Prest (1907-1985). Both won university scholarships to study history. But their family backgrounds and life trajectories were very different.

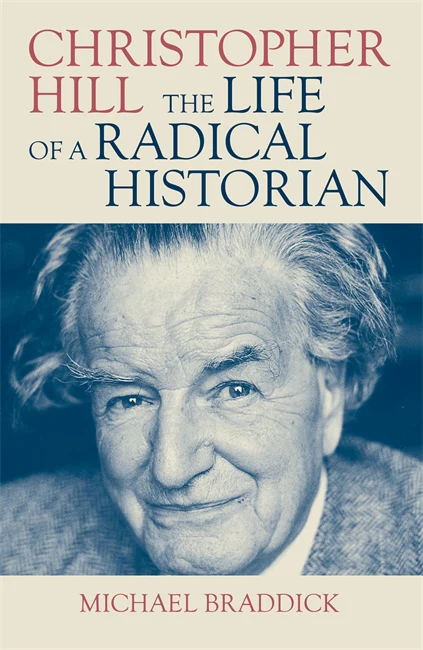

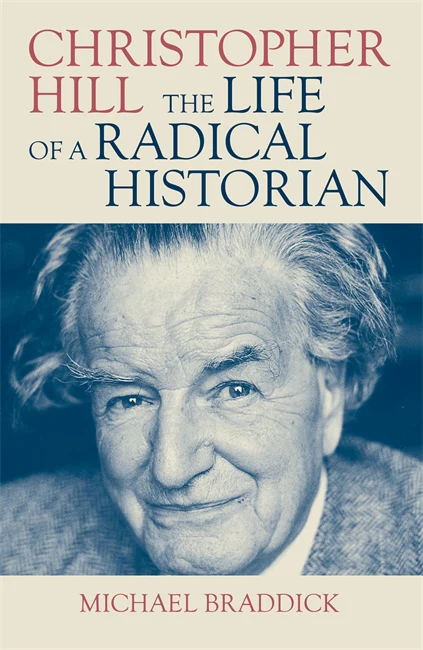

- Book 1 Title: Christopher Hill

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life of a radical historian

- Book 1 Biblio: Verso, £35 hb, 320 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Christopher Hill (1912-2003), son of a well-to-do Methodist solicitor, went south from Saint Peter’s School, York, to Balliol College, Oxford (founded 1263), after its history dons persuaded him to take their scholarship rather than one he had already accepted from Trinity College, Cambridge. Capping a brilliant undergraduate career with an All Souls College prize fellowship, followed by two visits to Stalin’s Russia and a brief lectureship at Cardiff, Christopher returned to Balliol as history fellow and a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). After the war and following his 1957 resignation from the party, he became widely – if never universally – recognised as the pre-eminent historian of seventeenth-century England. On retiring from a twelve-year term (1966-78) as Master of Balliol, he remained an active scholar well into his eighties. In all, Hill published some ‘eighteen books and seven volumes of essays, as well as major source editions and hundreds of reviews and other [works of] journalism’.

Dad, an Anglican small shopkeeper’s son, was educated at Archbishop Holgate’s Grammar School and Leeds University (founded 1874). After graduating in history and economics, he moved to Manchester for postgraduate study, then migrated with my mother to the University of Melbourne in 1938. There he conducted a major social survey of housing and incomes in wartime Melbourne and its suburbs, published many papers and reviews, eventually headed a large teaching department, chaired the Professorial Board, and served on the Commonwealth Grants Commission. Woefully conservative in my youthful eyes, whatever misgivings he may have felt about my Oxford tutelage under a former communist were not shared with me.

He had no need to worry. A mixture of cheerful informality and personal reserve was Hill’s hallmark as a teacher. Several appreciative generations of former Balliol undergraduates, widely diverse in their political and religious allegiances, can testify to his total lack of interest in ideological proselytising. Braddick also notes that the majority of Hill’s ‘most loyal, successful and grateful students were not Marxists’; among them were Sir Keith Thomas, former president of the British Academy, and our own Hugh Stretton, ‘to take the two most eminent’.

Balliol College, Oxford (Lebrecht Music & Arts/Alamy)

Balliol College, Oxford (Lebrecht Music & Arts/Alamy)

Hill is fortunate in his biographer, a distinguished early modernist who has worked hard to track his subject’s life. There are few personal papers, other than working notes. But many people who knew him are still alive and some of his outwards correspondence survives. He also figures in numerous memoirs and institutional archives, not least those of Britain’s MI5 and Special Branch.

State surveillance began following his first trip to Russia in 1934 and his file remained open even after he left the party in 1957. Hill only became aware he was being watched in 1952, on receiving a letter which had been opened, read, and replaced in the wrong envelope. But the security services had already cleared him to work on Russian matters in the Foreign Office during the latter stages of the war, and for a previous posting to military intelligence. His politics were not then seen as a threat to state security. Even in the more divisive immediate postwar years the main interest of his watchers was evidently whatever they might glean about the activities of Oxford communists and ‘fellow-travellers’.

But, in the polarised late 1970s and Thatcherite 1980s, public revelations of Russian moles and spies in high places fostered accusations about Hill’s wartime and subsequent loyalties. Combined misunderstanding and right-wing myopia or paranoia even led one of his academic antagonists to interpret Hill’s opening remark when they met in 1985 – ‘You are not going to unmask me, are you?’ – as an admission of guilt. Anyone familiar with Hill’s distinctly dry sense of humour would have recognised this joke for what it was, especially given his consistent denials that he had ever operated as any sort of undercover agent. Some of the smear inevitably lingered.

Braddick’s admirably clear-headed unravelling of these episodes provides a fitting coda to his account of Hill’s relationship with the CPGB, highly productive in intellectual terms – particularly his chairing of the Historians’ Group and founding of the journal Past and Present – despite ultimately irreconcilable clashes with the party’s apparatchiks. He is particularly interesting and perceptive on Hill’s early intellectual formation, his search for a role in life and his developed approach to history. This rejected both idealism and economic determinism, favouring a liberal ‘humanistic Marxist’ emphasis on the material contexts which create social circumstances where particular beliefs and ideas either flourish or wither.

No hagiographer, Braddick recounts early criticism of Hill’s approach to historical evidence, a theme reiterated by hostile reviewers of his Intellectual Origins of the English Revolution (1962) and other works. More broadly he traces the rise and decline of Hill’s scholarly reputation following his 1940 tercentenary essay ‘The English Revolution 1640’, which was widely regarded as the work of a clever but dogmatic Marxist. Economic Problems of the Church (1956) gained him greater respect, reinforced by essays, reviews, and the innovative textbook Century of Revolution 1603-1714 (1961). Hill’s standing peaked in the 1970s, after his bestseller The World Turned Upside Down (1972), which matched the counter-cultural mood of its times by recounting the upsurge of ultra-radical activists and individuals in the tumultuous 1640s and 1650s.

But critical revisionists were already decrying Hill’s reliance on printed rather than manuscript and archival sources, his seeming lack of interest in political history and his insistence that England’s revolutionary crisis and its aftermath were best understood as products of long-term socio-structural change, not short-term contingent causes. During the Left’s rout, from the 1980s onwards, Hill was increasingly cast as yesterday’s man: one of his most distinguished former students told me in the early 1990s that he could hardly recall any of Christopher’s writings with which he was still in broad agreement. But historians have always had short half-lives and few if any have matched Hill’s ‘totalising ambition and moral seriousness’.

For a self-professed intellectual biographer, Braddick is also fascinating on Hill’s childhood and family relations, wide-ranging literary interests and linguistic competence (in Latin, French, German and Russian), egalitarianism and physical robustness, views on love and sex, and his lovers and marriages, especially the happy partnership with Bridget, his second wife, no mean historian herself. Inevitably, he may not always get things quite right. There is no mention of the last-minute candidacy of the warden of Rhodes House for Balliol’s mastership, which helped split the anti-Hill vote and thus secure his electoral victory, while his subject’s dislike of All Souls (‘the snakepit’) surely sprang less from that institution’s ‘hyper-intellectualism’ than from its personal and political dynamics in the 1930s. There is little on Hill’s influence beyond the United Kingdom, although the University of Adelaide’s history department was once seemingly staffed largely by his former students. But such minor gaps scarcely detract from a perceptive reconstruction of a remarkable scholarly life both in and out of politics, and its contribution to the general history of twentieth-century Britain.

Comments powered by CComment