- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Why Twain, why now

- Article Subtitle: A Mark Twain paradox

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Ron Chernow is a renowned journalist and bestselling biographer, whose best-known work is probably Alexander Hamilton (2004), the main inspiration for Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton: An American musical (2015). Chernow’s latest book joins several acclaimed biographies of Mark Twain that have appeared in recent decades, including Gary Scharnhorst’s three-volume Life (2018, 2019, and 2022). The complete Autobiography of Mark Twain, also in three volumes, was published in 2010, 2013, and 2015. Twain dictated much of this to Albert Bigelow Paine, his authorised biographer and literary executor. As Chernow reflects, ‘The challenge for Paine, as for all future Twain biographers, was that Twain was peerless at bending the truth.’

- Book 1 Title: Mark Twain

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen Lane, $95 pb, 1200 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780525561729/mark-twain--ron-chernow--2025--9780525561729#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Mark Twain was the pen name of Samuel Clemens, who was born in 1835, in Florida, Missouri, the sixth of seven children of John Marshall and Jane Clemens. The family would move to Hannibal, memorably revisited in his fiction, a few years later. Only four of the seven children survived into adulthood. Their father, ‘[s]tymied by ill luck, battered by hardship’, died when Sam was twelve. His brother Henry died at the age of nineteen from burns sustained when a steamboat boiler exploded. Sam, by then a steamboat pilot, blamed himself for the rest of his life for having persuaded Henry to join him.

Clemens’s employment on the Mississippi River was ended by the Civil War (1861-65). Early in the conflict, he briefly joined a militia unit known as the Marion Rangers. He escaped from Missouri under the protection of his older brother Orion, a supporter of the Union, who had been appointed secretary of the newly formed Nevada Territory. In Nevada, Clemens speculated in mining shares and became an editor of the Territorial Enterprise, to which he had been submitting satirical sketches. He adopted the pseudonym ‘Mark Twain’ in 1863.

Chernow generally refers to ‘Mark Twain’ from this point in the biography, reserving ‘Sam Clemens’ for his subject’s private life. Twain became the first person to claim his ‘pen name as a trademark, suing pirated editions on that basis’. Twain’s most successful early story, ‘The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County’, was told to him by an old river-boat pilot named Ben Coon, in a Californian tavern. Although named as the source, Coon was apparently never remunerated, despite Twain’s later preoccupation with copyright.

Twain next sought employment at the Sacramento Union, which sent him to the Sandwich Islands (Hawaiʻi ) where he produced a series of travel letters. Once back in California, Twain gave a public lecture on the Sandwich Islands. Chernow comments: ‘The impact on Mark Twain’s career cannot be overstated. He … discovered his ability to project a theatrical persona that was a heightened version of himself.’ After a successful lecture tour in the west, he joined an excursion to Europe and the Holy Land, where he wrote articles for several newspapers in the United States. These would form the basis for the satirical travelogue The Innocents Abroad (1869), Twain’s most commercially successful book during his lifetime.

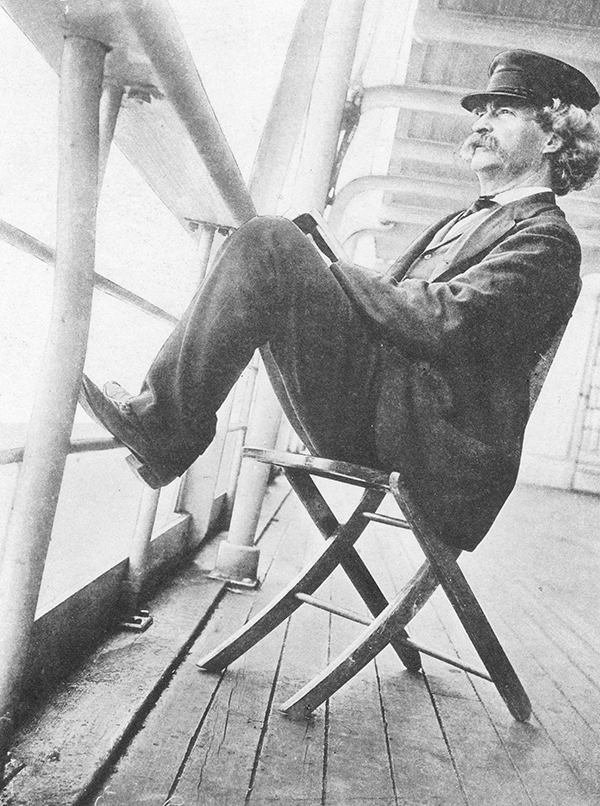

Mark Twain (Science History Images/Alamy)

Mark Twain (Science History Images/Alamy)

A fellow traveller on this excursion was eighteen-year-old Charlie Langdon, ‘the son of a coal and timber mogul’. Twain was enchanted by a miniature portrait of Charlie’s sister Olivia and subsequently pursued her in New York. With the Langdon family, he attended a reading by Charles Dickens, who was in the middle of an exhausting but lucrative final tour. The career of Dickens in many ways anticipated that of Twain, but on that auspicious night he had only criticism for the great English celebrity. Olivia, ‘Livy’, had suffered a mysterious paralysis for much of her adolescence, and would never be physically strong. Twain appears to have been attracted to both her intelligence and her delicacy. Livy was an heiress, ten years his junior, and her father’s approval of the incongruous match came as a surprise to the suitor.

Twain’s family was the source of his greatest happiness and his greatest grief. In 1872, shortly after the birth of their second child, Susy, their son Langdon died of diphtheria at the age of eighteen months. Clara was born in 1874, and Jean in 1880. All the girls were musically talented, but also prone to depression and anxiety. Susy died of meningitis at the age of twenty-four, while her parents were in Europe. Twain had encouraged her interest in ‘Mental Science’, a program which emphasised the individual’s spiritual power to heal illness. Susy’s subsequent refusal of conventional medical treatment may have cost her life. Livy passed away at the age of fifty-eight, of congestive heart failure. Having long suffered from epilepsy, Jean died unexpectedly, during an apparent heart attack, on Christmas Eve, 1909. Twain’s passing followed four months later. Only Clara would survive her father. Her daughter, Nina Gabrilowitsch, was the last of Twain’s recognised descendants.

Twain was culpably naive in most business dealings, repeatedly lured into get-rich-quick schemes. An astute commentator on human nature in writing, he was an easy target for conmen and spruikers and was declared bankrupt in 1894. Unfortunately, as Chernow remarks, both Twain and Livy were ‘addicted to luxury’. To repay his creditors, he embarked upon a last, extended lecture tour, which included a well-received sojourn in Australia and New Zealand. A contract for the rights to his works with Harper & Brothers in 1903 restored some financial security.

A problematic matter for Twain enthusiasts is his enduring fondness for girls between the ages of ten and sixteen, which became obsessional after the death of his wife. Twain referred to these children whom he befriended as his ‘angelfish’, insisting on frequent exchanges of letters and extended visits. This predilection seems to have been largely dismissed as an endearing eccentricity during his lifetime. Clearly uneasy on the subject himself, Chernow points out that Twain was never accused of acting improperly – ‘[t]hough, heaven knows, his actual behavior was odd enough.’

As Chernow notes, Twain had ‘soared to the zenith of his fame long after his fiction career had largely ceased’. In the twentieth century, film adaptations extended his reach. Well into the twenty-first century, his legacy is still evolving. If there is something of a resurgence of interest in Twain’s life and work, it is largely focussed on The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884). This still-controversial novel was Twain’s answer to a romanticised version of slavery. In 2024, Percival Everett’s novel James, a retelling of Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of Jim, won the National Book Award for Fiction and the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. Earlier this year, the respected Twain scholar Shelley Fisher Fishkin published Jim: The afterlives of Huckleberry Finn’s comrade. Beyond his most widely known works, Tom Sawyer (1876) and Huckleberry Finn, Twain’s diverse oeuvre manifests an abiding interest in the question of whether character is more greatly influenced by nature or circumstances. Hence the recurrence of the plot device of switched identities in The Prince and the Pauper (1881) and Pudd’nhead Wilson (1894).

Chernow offers insightful readings of Twain’s many works, illuminating the contexts in which they were written and the ways in which they were received. He might arguably have done more with the posthumously published The Mysterious Stranger (1916), an awkward synthesis of several draft versions of a novella set in the Middle Ages which was compiled by Paine after Twain’s death. Despite the criticism which has been levelled by scholars at this ‘bowdlerised edition’, the novella gives an insight into Twain’s mental anguish in his last years, ending as it does with a bitter repudiation of the notion of a loving God.

The life of Mark Twain is intriguing for its contradictoriness. He is generally remembered as a humourist, although his work is permeated with despair and rage. When he became disillusioned with someone, whether for valid reasons or otherwise, he became implacably vindictive. As Chernow expresses it, ‘he constantly threatened lawsuits and fired off indignant letters, settling scores in a life riddled with self-inflicted wounds.’ He alternated between self-castigation – especially for the suffering of his forbearing wife – and projection of his own failings onto others. An erstwhile Confederate soldier from a Southern slave-owning family, he refashioned himself as a Northern gentleman. He was a defender of the working man but relished the company of aristocrats and royalty. Having had little formal education, he took particular pride in the honorary doctorate bestowed by Oxford University in 1907. He was an admirer of the British empire who became one of the most trenchant critics of American imperialism. Angrily agnostic, he regarded a minister in the Congregational church as his closest friend and idealised Joan of Arc for her devotion. Although he always had empathy for African Americans and protested against the vicious treatment of Chinese immigrants, he never fully overcame his early contempt for Native Americans.

Twain’s overt scepticism concerning mob mentality, unexamined patriotism, and adversarial politics may account for his enduring appeal in our interesting times. Assessing his predecessor Paine, Chernow asserts that he ‘committed the cardinal sin of any biographer: his relationship with Twain began to metamorphose from professional detachment to unstinting friendship’. Even with a safely long-dead subject, though, a biographer can succumb to hyperbole. Encountering Chernow’s sweeping description of the ghastly Tom Sawyer as ‘the quintessence of American boyhood’, this reader wished that an editor had demurred. Twain, according to Chernow, is not merely ‘one of the world’s most remarkable men’ but the ‘most original character in American history’. Nonetheless, this very readable biography conveys a balanced portrait of Mark Twain, who manifested his nation’s vivid complexity.

Comments powered by CComment