- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A set to the chin

- Article Subtitle: History of argument, not narrative

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It is common today for historians to describe what they do as telling stories about the lives and events of the past, using the narrative techniques that they share with fiction writers: describing place, weather, clothes, the set of a leading character’s chin, and so on. But as a disciplined, evidence-based enquiry, history writing is also about argument and interpretation.

- Book 1 Title: John Hirst

- Book 1 Subtitle: Selected writings

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $36.99 pb, 336 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781760645748/john-hirst--john-hirst--2025--9781760645748#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

For John Hirst, historian of convict society, Federation, and Australia’s democracy and political culture, it was the argument not the narrative that drove his prose, which makes him particularly well-suited to the essay. The collection Black Inc. Publisher Chris Feik has put together shows Hirst at his best: provocative, clear-headed, and always interesting. It is prefaced by reflections from fellow historians Frank Bongiorno, Robert Manne, and Alex McDermott. Each knew him personally and each attests to his kindness and generosity, as well as providing thoughtful commentary on his distinctive oeuvre. This selection of Hirst’s writing is the most recent in Black Inc.’s admirable series on Australian Thinkers, joining volumes on W.E.H. Stanner, Judith Wright, Inga Clendinnen, George Seddon, Hugh Stretton, and Donald Horne, a stellar line-up of thinkers formed by twentieth-century Australia.

Hirst was a conservative social democrat who celebrated Australia’s democratic political culture and institutions and its egalitarian ethos. He supported Labor and its ambitions to improve the lives of working people, but was not uncritical of the party, regretting its opposition to conscription in World War I, which separated citizenry from soldiering, and rejecting the judgement of John Curtin as Australia’s best prime minister. He had, as well, an instinctive suspicion of the liberationist projects of the 1970s which Labor took up. ‘I do not have the temperament of a liberationist,’ he wrote, and ‘am very sympathetic to the problems of governing’, of creating the order which allows ordinary people to get on with their lives. He did not believe that the loosening of social ties and the questioning of all authority would lead to a better world.

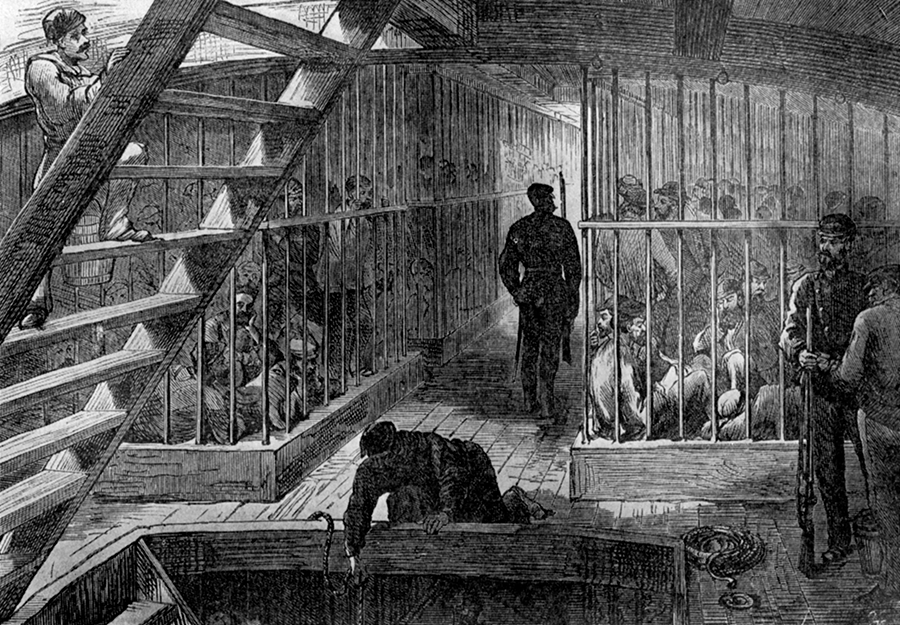

This dual focus, on the governed and the governing, is most evident in his history of convict Sydney’s early years. It was not, he argued, a living hell, a penal colony dominated by the lash, but is better understood as a colony of convicts. For the colony to become self-sufficient as intended by the British government, the early governors required convict labour and cooperation and so had to give Sydney’s convicts more legal rights than convicts back home in Britain. They could own property, give evidence, and bring actions in court; on becoming free, they were given thirty acres of land and their own convict servant.

Caged prisoners in a transport ship on the way to Australia, 1788 (The History Emporium/Alamy)

Caged prisoners in a transport ship on the way to Australia, 1788 (The History Emporium/Alamy)

Hirst’s writing circles a set of interrelated questions about the origins and character of Australia’s political institutions and culture. How did a penal settlement become a peaceful democracy? What is the nature of our egalitarianism? How to explain the coexistence of our imagined anti-authoritarianism and our habits of civic obedience? Why did the Australian colonies federate? What are the origins of our successful multiculturalism? His is the agenda of an older generation of Australian male historians concerned to explain what happened when British people, political institutions and ideas travelled across the globe to the Australian colonies. His questions may seem somewhat old-fashioned to many contemporary readers, but his answers are compelling.

Hirst is well aware of the violence and dispossession of the British invasion and conquest of land and he has a thoughtful essay on how we should think about this. Titled ‘How sorry can we be?’, the essay argues that it is hypocritical to decry the conquest of the land from which we have benefited. It is a liberal fantasy, he writes, to imagine that the nation could have come into being without conquest and a dark past; that violent conflict could have been avoided by good intentions and better communication. In this he describes himself as a hard-headed realist. The stealing of children by the state in pursuit of an ideal of racial purity is another matter: ‘Humankind has been very inventive in its cruelty, but cruelty of this kind did not appear until the early twentieth century.’

Hirst recalls that from his teachers of Australian history at Adelaide University in the late 1950s and early 1960s he learned ‘a sort of debased Marxism which looked to economic interests to explain events’. The nineteenth-century idealist historian Thomas Carlyle encouraged him to think differently about human motivation. Human beings do not live by bread alone but seek belonging and dignity, and so Hirst pays close attention to the vicissitudes of status in colonial Australia. Status was an unbreachable barrier between ex-convicts and free settlers, no matter how rich the ex-convict became. By the 1860s the Australian colonies were the most clamorous for British honours of all the self-governing colonies, as the dress and manners of the English gentleman spread to Australian merchants and men of business. Here, too, British working-class institutions like friendly societies, mechanics institutes, and labour parties lost their sectional class character and opened up to middle-class men and farmers. It is a contradictory story of status barriers being both maintained and loosened. Australian egalitarianism, Hirst argues, has never mainly been about economic equality. It is, rather, an egalitarianism of manners, in which men of unequal wealth and status are expected to address each other as equals, without expectations of deference or subservience on either side.

Status, and its close companion identity, are key to his explanation for the Federation of the Australian colonies. Federation, he argues, was not primarily a utilitarian, material agreement over uniform policies on customs, immigration, and defence but a noble cause, in which Australians would transcend their colonial status and parochial loyalties to become proud members of a new nation. This can be seen in the outpouring of popular verse, and is why Hirst called his book on Federation The Sentimental Nation (2000). It was, he said, a tribute to Carlyle, and to the idealists who saw Federation as a sacred cause.

Hirst mourned the way the civic nationalism of the Federation movement faded so quickly in popular memory. It might have become the moment when our political system became the embodiment of the nation, but it didn’t. Hirst was a committed republican and he worked hard in the lead-up to the ill-fated referendum of 1999. As a member of Keating’s Republican Advisory Committee, he greatly enjoyed travelling the country talking with ordinary people about their expectations of government. For Hirst, the remnant link with the British Crown was incompatible with Australians being a free and sovereign people and he thought it undermined attachment to our political institutions. Becoming a republic, he hoped, would create the moment of connection which Federation had failed to achieve. But we’re still waiting, and it may be that the moment for the sort of proud civic nationalism that Hirst hoped for has passed. When, in the lead-up to the referendum, I was sceptical about its chances of success, Hirst was dismayed. His generation still bridled enough at the indignity of the colonial remnant in our constitution to work for change. He doubted if younger Australians did or would.

Hirst was a citizen historian who used his historical research and knowledge to illuminate the present. Australia’s successful multiculturalism had its origins, he argued, in the determination of the nineteenth-century settlers to avoid the sectarian religious conflicts of Britain and Ireland and the practices they put in place to give the churches equal status. We may pride ourselves on being anti-authoritarian, he said, yet we are an obedient people, who will swear our heads off at a football match and then go outside to have a smoke as the law demands. Hirst died before Covid-19, but he would have been unsurprised by our generally uncomplaining compliance.

The photo of Hirst on the cover shows a clear-eyed, determined man with a slightly pugilistic set to the chin and mouth – as if he is half-expecting to be hit. He knew he was provocative, and that people would disagree with him. So, pick up this book, relish the clarity of his thought and his lucid prose, and have an argument with him.

Comments powered by CComment