- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

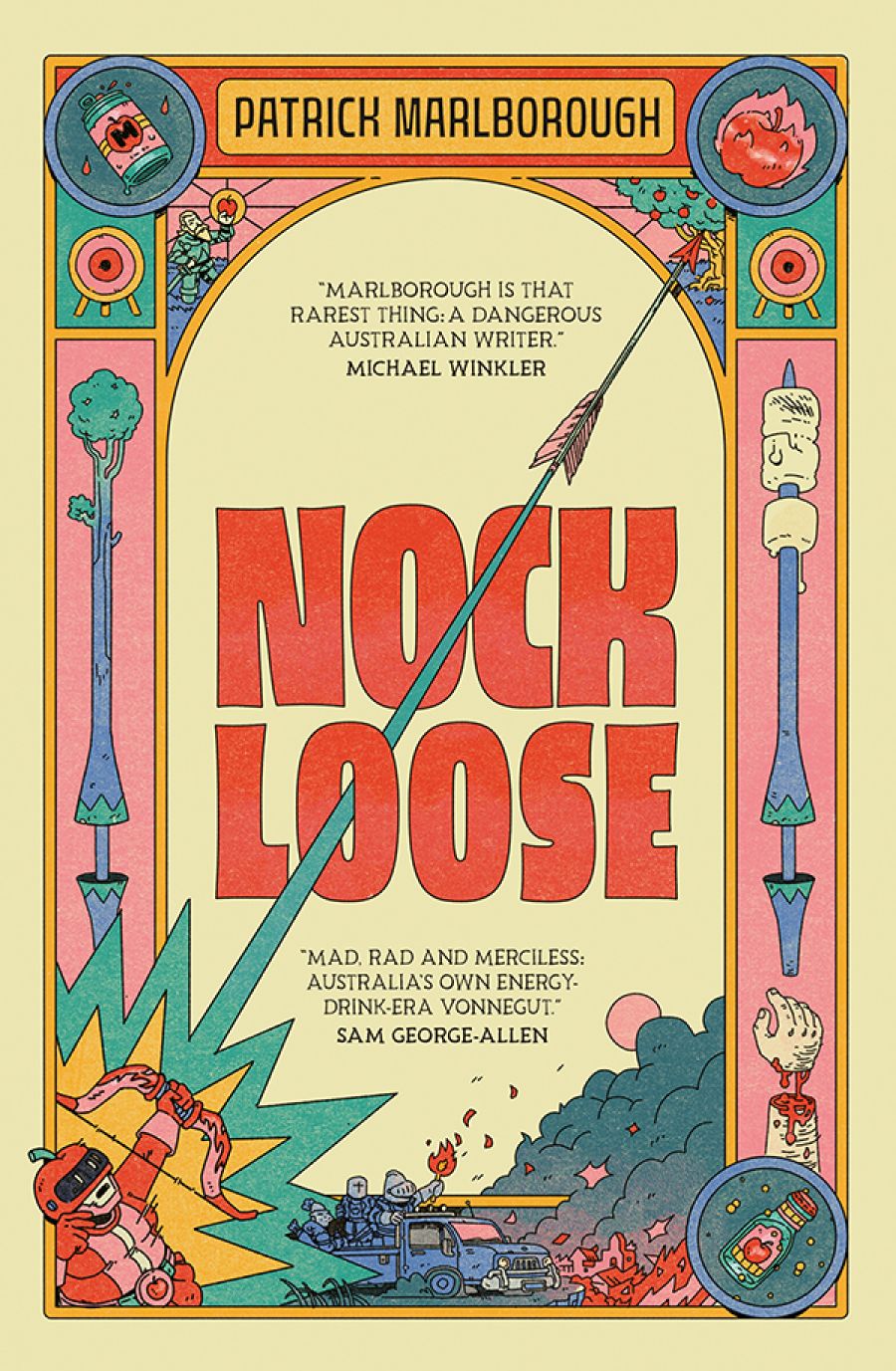

- Article Title: Bullseye!

- Article Subtitle: The novel comes to Agincourt

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australia is a weird place. A backwater colonial outpost settled by racist squatters and their indentured convict servants, it is a country forever defined by its isolation, in every sense, from the rest of the world. Faster than Barron Field could say ‘kangaroo’, an Empire crashed onto the shores of the First Peoples who had been cultivating a narrative tradition since time immemorial, and set about writing a (manifest) destiny of its own.

- Book 1 Title: Nock Loose

- Book 1 Biblio: Fremantle Press, $34.99 pb, 288 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781760995072/nock-loose--patrick-marlborough--2025--9781760995072#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

If we bring all the characteristics of an early settler-colonial literary culture into the harsh light of the present, as Patrick Marlborough astutely does in the postscript to their debut novel, Nock Loose, what are we left with? For Marlborough, it is a ‘dire humourlessness’, ‘ever-tedious’, borne from a country with ‘incredibly thin skin’. It is nearly impossible to disagree with this assessment. One need only look through the archive of this very magazine (and any other) to witness the nervous breakdowns that so often ensue when the Australian writer is cut down to size by the Australian critic. So, in this ever-critical spirit, Marlborough’s solution – what they have affectionately dubbed ‘Piss Take Lit’ – is taking the ossified form of the middlebrow Australian novel in a thrilling and unpredictable new direction.

The novel’s inspiration began in 2016 with Marlborough’s assignment by VICE (a now-defunct internet magazine) to the town of Balingup in their home state of Western Australia, to report on the annual Medieval Carnivale, where they observed ‘a knight in speed-dealers bowling over children in a muddy little arena’. Such an unholy matrimony of subcultural nerd-fantasy and bogan Australiana is where Nock Loose situates itself. To Marlborough’s great credit, no novel published in this country thus far (at least that I can think of) has dared to take on such, um, unique material.

The novel is largely about the life of Joy, a prodigal, once-Olympian archer who is now in the throes of middle age (Marlborough states Magda Szubanski ‘MUST play Joy in the Stan Original’) and serious, serious grief. Her house has been burned down, her granddaughter Hannah and much of her most cherished archery paraphernalia lost in the blaze. Half the town of Bodkins Point has been gutted by the fire, started by a ute-load of drunken hooligans in faux-medieval chainmail.

Between the present day and flashbacks to Joy’s upbringing with her hopeless, quixotic father Conway (or ‘The Bugger Bandit’, as he’s known among Bodkinites), we learn that Joy has a preternatural talent for archery, which began at an early age. It led her to the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, where she met Japanese twins Yasuko and Nobuko, themselves archers, who introduced her to the anime industry.

Joy was cast as a stunt double in the live-action adaptation of the manga comic Sukeban Yumi, and in a hysterical scene between her middle-aged self and the sixteen-year-old manager at the Bodkins Point IGA, Ira Bodkin (a distant cousin of the town’s settling family, the Bodkins, not-so-affectionately known as ‘the Orc’), we are introduced to this strange chapter of her past through Ira’s bewildered viewing of a YouTube video titled ‘Sukeban Yumi trickshot compilation’. After the fires and on the precipice of Agincourt 2023 – the annual Renaissance Fair/drunken bloodbath that is the epicentre of both the town and the novel – Joy is forced to reactivate this dormant superhuman skill.

This is as brief a summary as I can give of what is a truly rich and ridiculously entertaining novel. Marlborough has not cut corners in building a self-contained universe in Bodkins Point, replete with lore (the appendix contains several sources from the fictional town’s history, from the folkloric ‘Ballad of the Bugger Bandit’ to archival forum posts, to a list of Agincourt’s ‘DOTHS & DON’TS’). Furthermore, the novel is truly contemporary. At a glance: reigning King Arthur Bodkin founds a cryptocurrency called ‘BodCoin’ to supplement the physical currency Agincourt lost in the fires. One of the Bodkin sons starts an energy drink company called ‘Munter Energy’. One of the book’s chapters is Sukeban Yumi’s Wikipedia page, fully typeset in Wikipedia’s style.

In this way, Marlborough’s cultural obsessions are brought to bear on the novel through a dense intertextual network of references, in-jokes, and temporal shifts. As someone who also spent their teenage years trawling Wikipedia pages, playing esoteric video games, and reading even-more-esoteric literature, it is refreshing to see the novel choose a subcultural object that seemingly is not literary in the slightest, and make it so.

While it is worth noting that Marlborough is perhaps too eager to explain all their intentions, you cannot blame them for having a sense of pride in their ambitious debut. Marlborough has written a novel that, to my mind, marks the advent of an Australian counterpart to the works of Thomas Pynchon – the kind of zany, kaleidoscopic ‘postmodernism’ that never really reached Australian shores (even our modernism was a few decades late).

As in Pynchon’s novels, the comedy is only one part of a much more complex and contingent arrangement. The absurd personalities and events that pepper the novel are signifiers for a possibility latent within the novel’s form that Marlborough is beginning to crack open. As Marlborough acknowledges, this all takes place on land stolen in a historic genocidal rupture, the legacy of which endures in White Australia. These rituals of violence, while ridiculous and comical, are nevertheless rooted in a history of dispossession and erasure that most Bodkinites choose to ignore. However, the subcultures to which Marlborough pays loving homage are attempts at finding, or building, collectivities in the face of this increasingly atomising force. Without spoiling the novel’s end, it is these collectivities that endure – and it is these collectivities upon which a robust literary culture depends.

Comments powered by CComment