- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Calibre Prize

- Custom Article Title: ‘Consolation of Clouds’

- Review Article: No

- Article Title: Consolation of Clouds

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the quiet years between my father’s death and my stepfather’s eruption into our lives, my mother, my sister, and I lived with my grandparents for the longest time in the last of the houses that look like that. You know, little and squat, red brick with a red-tiled roof and a wooden sunroom-cum-sleepout propped against the back wall and, all about, when you spread your arms and spin, red roses and metal-blue hydrangeas and pumpkins on hairy stalks and a red incinerator made of tin and fruit trees shining with apples and oranges and loquats with big pips.

My mother and grandmother often prepared a six-foot-long trifle on the painted table my father had built out of a door, which I still have in my kitchen. They bought yellow sponge cake, which they covered with jam and brandy. ‘Don’t touch,’ they’d tell us if we stuck our fingers in the soggy edges. Instead, my grandmother would toast us leftover collars of bread that had been cut from around little white party sandwiches. ‘Have as much butter as you want.’ ‘Eat them while they’re warm.’ I would pop them on my wrist like bangles.

One day my mother spilled a tureen of cooked peas onto the linoleum just when we were packing the Holden with food for a party in posh Toorak. Everyone stood still. For a long minute my grandmother held Spats the border collie back with her foot. Then she started to laugh, and my mother grabbed the broom and swept the peas back in the pot and popped the tureen in the car. ‘What they don’t know, won’t hurt them,’ said Mrs Collins.

To pass the time between other people’s parties, we would project my late father’s slides onto the kitchen wall. The kitchen was the only room where the slide projector could be propped far enough from a wall to produce a focused image.

My sister would perch, dangling one leg, on a high, cane barstool, which she liked because she was the smallest of us. We had to drag my grandfather’s chair in from the sunroom because the kitchen chairs wouldn’t take his weight. His chair stood in the centre of the kitchen, and he would set the mood and rhythm of our viewing with his deep, musical humming. I liked to sit on his kind lap, feeling his warm whisky breath on the back of my neck and the soft cotton of his striped pyjamas. When the old slide projector overheated, well into the evening, a slide would melt to a yellow smudge on the wall, with a tell-tale whiff of cooked dust and plastic. The slides were mostly of clouds, which my father had photographed from his plane. We became familiar with them all: the cottony cumulus, the dark wool nimbus, and the fine lines of cirrus, like pulled threads in a plain skirt.

My mother fussed with the projector, which could tilt suddenly, as though it were tired, casting the clouds onto the floor.

My grandmother, my great-aunt Nancy, and the lady from down the road whom we called Auntie Ruth sat along the wall on a row of straight-backed kitchen chairs, holding glasses of hot sugared whisky and little round cracker biscuits. Every so often Nancy would say, ‘Nice cloud.’

We would all agree. Whenever my grandfather picked up the pace of his humming, Spats, who sat tall on the yellow lino at our feet, would howl in time to the music, and my grandmother would uncross her elegant legs, lean forward and reward him with a cracker.

As a child, I cherished a silver plane on a stand, its solid body set at an angle to the base as though the plane were taking off. I read lots of pilot stories, too, like Biggles Sees it Through, and Worrall’s (a woman pilot!) on the Warpath. Douglas Bader was my hero. He flew with the British during World War II, despite having both legs amputated after an aerobatics crash. I read that having no legs made him a better Spitfire pilot, less prone to fainting when gravity sucked blood away from his head.

When my mother, sister, and I moved far from my grandparents’ house, I placed the plane and a photo of my father on my new bedside table. Three months after our move, my mother married a man, who came to live with us. I thought this plain old man would be sleeping in the bath, as there were only two bedrooms. He hit me the first night he was under our roof.

It strikes me as odd, looking back, that he didn’t spend a moment wooing us.

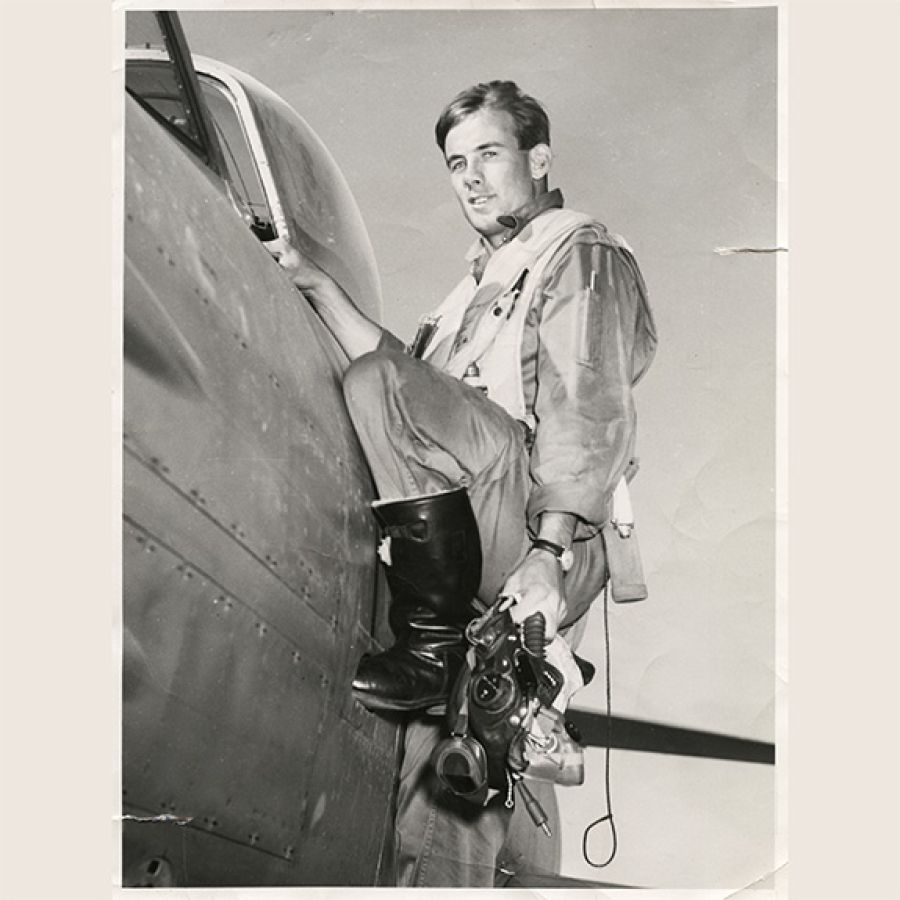

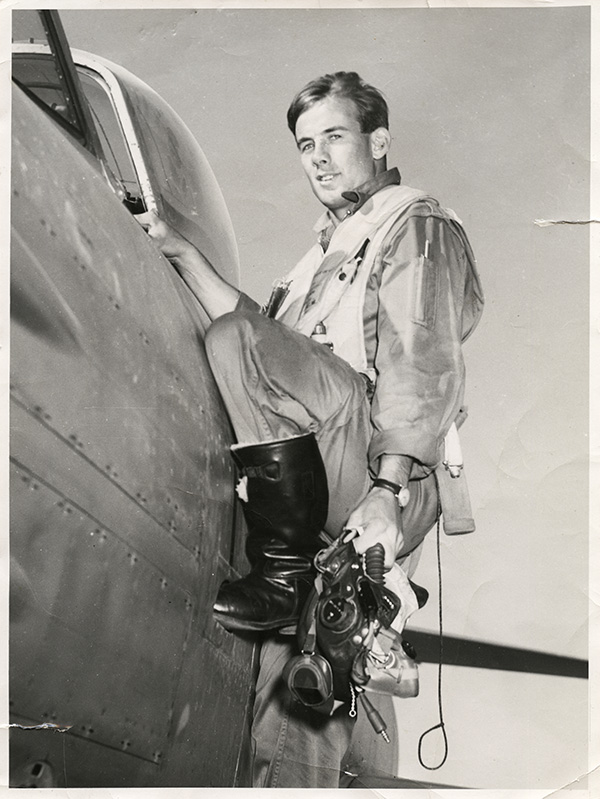

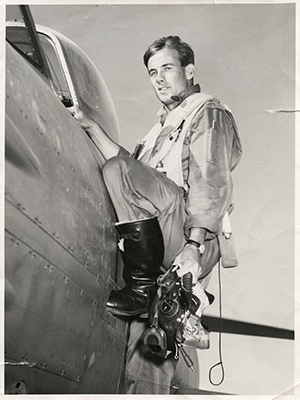

I collect images of my father. There are a fair number about. My father was a Face. Each era has them. The good-looking, robust, trustworthy face that makes all sorts of untrustworthy people straightaway want to use that face for advertising. When he returned from the Korean War, a poster of my father was pasted in the Melbourne trams. He was posed in dress-up camouflage, silly stuff, leaves and grass, pretending to be grievously wounded while another young man gently tended to him. I wonder what those faces said to the tram-riding public in the 1950s. Come, join us; you will be terribly hurt but will be met by great gentleness from other men before you die?

My father was in the initial officer training course for the Royal Australian Air Force. The trainees holidayed together, skiing or canoeing. In the creased photo I obtained through one of his cadet pilots – an old man now – my father stands, carefully guiding a group of men as they build wooden canoes for a trip. To have such a father!

I remember my father smiled a chipped-tooth smile and the skin around his blue eyes crinkled. He took me to work with him on the Williamtown Air Force base near Newcastle while my mother was in hospital, giving birth to my sister. He swung me onto his shoulders and the guard saluted my teddy. My father said when I grew up he would take me in a silver plane, and we would fly a loop-de-loop.

Flight Lieutenant G.A. Boord, c.1953 (Courtesy of the author)

Flight Lieutenant G.A. Boord, c.1953 (Courtesy of the author)

When I imagine my father piloting his fighter plane through freezing air over Korea, I hear James Salter’s voice: cool, precise, knowing his stuff. James Salter wrote a book about the Korean War, called Gods of Tin: The Flying Years (2004). He flew one hundred missions.

My father also flew one hundred missions in Korea and was Mentioned in Dispatches as a good leader and aggressive. (It has taken me years of reading about that war, to try to unpick why Australian pilots were there, always in the wake of Americans; to understand whether my father was doing good. This is not that story.) Both men are dead, of course. The daughters of living fathers do not tend to flutter about them like this, more than half a century later.

A friend of my mother’s visiting Sweden once saw my father’s face repeated across the window of a bookstore in Stockholm. He was on the cover of a Swedish air annual: Ett År i Luften 1955, the year of my birth. His face is shades of grey, slender, alert. Perhaps there are no coloured images of him.

My father looks directly at me from the cockpit of the plane.

In 1957, after the Korean War, he was forced to ditch a Sabre into the sea off the Australian coast. He had to bail out. There is quite a bit known about his ejection. He was the first person to use the Sabre’s ejector seat. I have an earlier photo of him seated in the plane with the words Danger Ejector Seat clearly visible. At first, I found this photograph unsettling and planted my thumb on the word Danger.

The use of an ejector seat in a plane flying at jet speeds was gently promoted in 1950s air force articles: ‘The ejection seat and the pilot are both thrown high into the air above the plane where he becomes separated … He and the chair descend separately to the earth in safety by means of parachutes.’

After the accident my father reported to an Air Force inquiry into the loss of the valuable Sabre. According to my grandmother he told them that the plane was spinning, the engine was not responding. My father had spoken to Base: ‘I am ejecting.’ His seat belt wouldn’t release. He tugged it open, ejected with his seat, knocking his head on the plane’s canopy. His body hit a punishing stream of air. He kicked free of the heavy ejector seat. His parachute opened then collapsed around his body as he smacked face first into the sea. His vest choked him around his throat. The parachute rig was snagged around his body, dragging him underwater. He surfaced into the light. Later, a fisherman saw him glinting, silvery in the water, and fished him out. The parachute shroud lines had to be cut from his boots.

I try to imagine my father saving his own life, at speed, in the face of shocking obstacles. It strengthens me, somehow.

Some fifteen years after the crash, when I was a teenager, a walker found my father’s plane in a sand drift not far down the coast from the Air Force base where we had lived. There was a short article in the papers, which my grandmother cut out with her nail scissors, and laid with other articles into the last gift he gave her, a shallow stocking box with a firm glossy cardboard lid, which in turn she left to me.

It’s not known if the accident was due to pilot error, a failure to recover from a non-oscillatory spin, or the failure of a speed brake mechanism. As the navy could not recover the plane, a conclusion could not be drawn. The Canberra Times in 1960 notes that in the three years following my father’s ejection three pilots from the same base attempting to eject from their aircraft had died. The dramatic Sun-Herald headline at the time of my father’s crash was ‘A young jet pilot went purple after pulling the Next-of-Kin switch’.

Within days of the crash, my father developed black spots on his face. The newspaper reports mention them, but medical reports do not. I wonder. Perhaps he had a heart attack when he ejected?

My sister was born four months after the crash, in January 1958.

A few days after her birth my father was inoculated against several diseases prior to returning overseas. He came home feeling queasy. My mother and I and the baby were sweltering in the January heat in our Air Force house. My father asked my mother not to eat her lunch in front of him. He lay on his bed growing sicker through the afternoon. His mouth turned blue.

We had no phone. My mother ran to a neighbour. The base doctor was away, and a Newcastle doctor came too late and declared my father dead. He was twenty-seven years old. Autopsy findings were inconclusive. His death may have been a reaction to the vaccination, coming on top of an earlier insult to the body.

So, my father did not die in Korea, where so many pilots died, nor later when he crashed his plane off the Australian coast. He died at home with us when I was three.

I have learned to remember my dreams by writing them down each morning. I have a fantasy that is like a waking dream. I am an astronaut looking at earth in the blazing light of morning. Gravity has loosed its hold and I loop, in neat, smooth somersaults, through the light. In the real world, I receive the illustrated, irregular newsletters of the Cloud Appreciation Society. I have their enamel cloud-shaped badge and am, I believe, member 6556.

‘Consolation of Clouds’ placed third in the 2025 Calibre Essay Prize. Calibre is worth a total of $10,000, of which the winner receives $5,000. The Calibre Essay Prize was established in 2007 and is now one of the world’s leading prizes for a new non-fiction essay. The judges’ report is available on our website.

ABR gratefully acknowledges the long-standing support of Patrons Peter McLennan and Mary-Ruth Sindrey.

Comments powered by CComment