- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: For her devotees

- Article Subtitle: Deborah Levy’s eccentricities

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Readers grow faithful to their favourite authors – to their style, their literary landscapes, and the moods their books create. Readers of Deborah Levy’s work have come to know and love her idiosyncratic voice. Her texts plunge readers into quotidian worlds made surreal and her narrators point out the humour and strangeness of everyday life.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Beth Kearney reviews ‘The Position of Spoons: And other intimacies’ by Deborah Levy

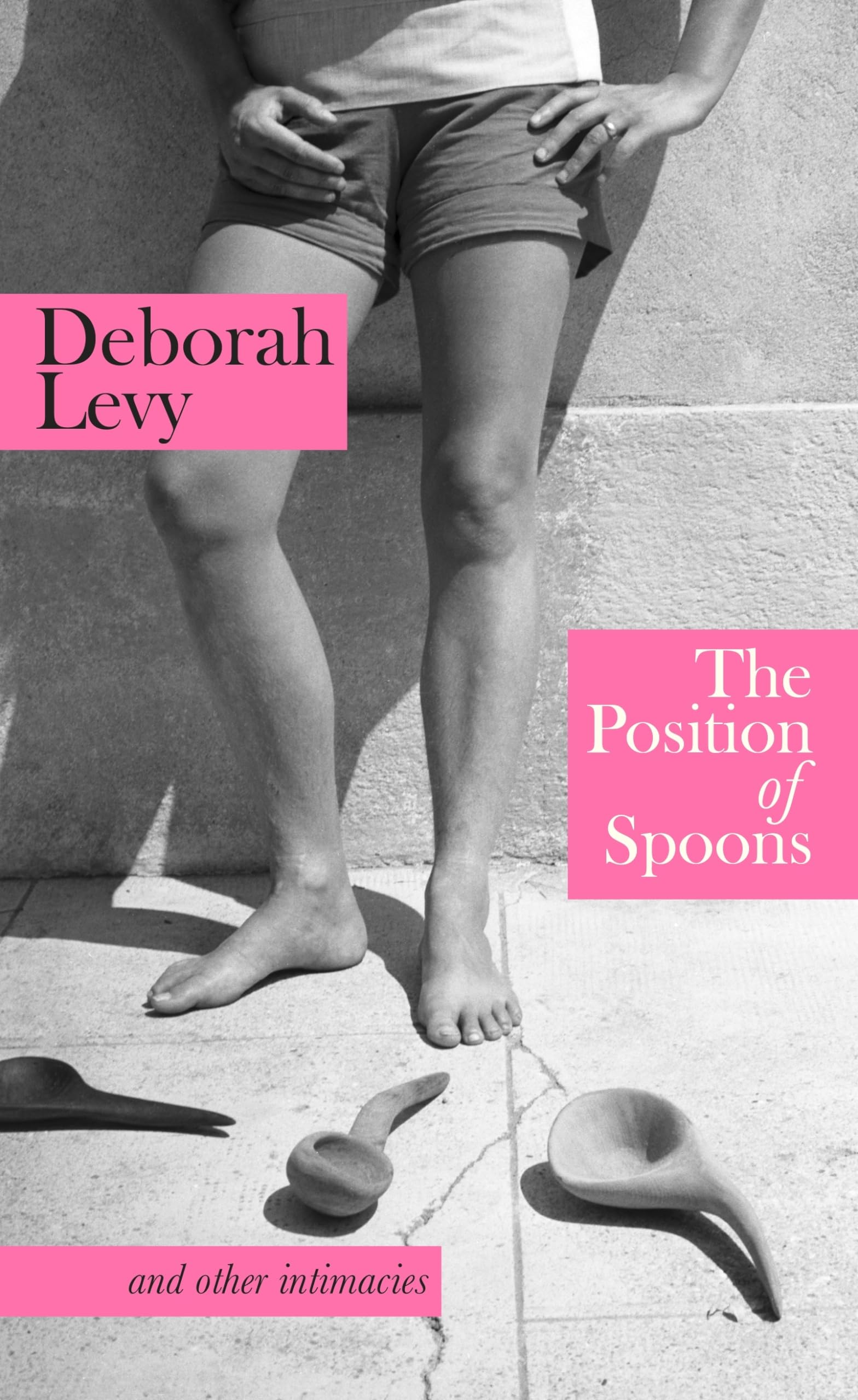

- Book 1 Title: The Position of Spoons

- Book 1 Subtitle: And other intimacies

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $24.99 pb, 240 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780241674505/the-position-of-spoons--deborah-levy--2024--9780241674505#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

The most striking essays contain reflections on writers and visual artists. In them, we learn a lot about Levy – her tastes in art and literature, her inclination towards the bold and bizarre, her mind as a young woman discovering herself and her inspirations. Unsurprisingly, Levy admires women creators who tested the limits of femininity in both art and life. There are essays on Colette, Marguerite Duras, Lee Miller, Méret Oppenheim, and Francesca Woodman – iconic figures who were exploited because they were women. Colette’s first husband published her books under his name and Miller is thought to have discovered the photographic technique of solarisation, a breakthrough initially credited to her lover and collaborator of the interwar period, Man Ray. The women that capture Levy’s attention lived ‘experimental’ lives – Miller is a key example, as she was one of the few war photographers working alongside Allied forces in Europe in 1944-45 – and their audacity shines through in their creative work. Levy writes of the powerful symbolism of Woodman’s photographs, in which young women are continually in the process of disappearing, dissolving into walls and windows, and escaping beyond the frame of the image: ‘It is so important to have a grip when we walk out of the frame of femininity into something vague, something more blurred.’

Levy’s work on great artists calls attention to the creative and experiential boundaries that she also has pushed. The second volume in the Living Autobiographies trilogy is a case in point. In The Cost of Living (2018), she writes about societal expectations for women and leaving her marriage.

Many of the figures that Levy writes about were surrealist or neo-surrealist creators, and we recognise in Levy’s oeuvre this same legacy of surrealism. The objects in Levy’s worlds tend to take on ambivalent and nonsensical meanings. Her characters are often displaced and in the process of discovering new landscapes. The mundanity of the world evaporates in Levy’s work, as her sentences start somewhere ordinary and finish somewhere else, somewhere a little more luminous, dramatic: ‘Is there a single silver teaspoon that has not stirred up the memory of seduction and rage?’ With these unexpected drifts, Levy disturbs thought, upsetting patterns of seeing and being in the world.

While some contributions illuminate aspects of Levy’s practice, others do the opposite. One describes the gaze of ‘a particular middle-aged woman’ who ‘had eyes that seemed to want to disappear into her head’. This scene might inspire a remarkable surrealist painting, but the short passage is too brief to explore a bigger idea or propel us into a more immersive narrative, as occurs in Levy’s most recent novel, August Blue (2023). In ‘Telegram to a Pylon Transmitting Electricity over Distances’, a daughter mouths the words to songs in High School Musical, but Levy fails to show her readers why they should take interest in this scene. Nestled in between insightful exercises in creative literary or art criticism, these short contributions seem like filler to meet a word count.

Rachel Cusk has also achieved worldwide renown in part through her experimentation in first-person writing. In a 2021 inter-view with the Norwegian author Linn Ullmann, Cusk explains that she now only publishes if she is saying or doing something new: ‘This is not a time for culturally established people, if that’s what I am, to take up more space.’ Though she recognises that this attitude is perhaps gendered (many men don’t mind if they are taking up space), she maintains that by producing more of the same one can ‘end up cluttering up the place and wrecking the environment’. Reminding us of her own literary voice – categorical, unapologetic honesty – Cusk asks: ‘What justification can you offer for adding to the noise?’

For some, however, diving back into the familiar can be a great delight. For Levy’s devotees, The Position of Spoons will be another encounter with her stylistic eccentricities and humorous mode of looking at the world. Others will find many essays in The Position of Spoons to be as their literal English translation suggests: attempts, or first drafts, humble bursts of inspiration that might later become great works of art. Such contributions do not measure up to Levy’s radical experiments in style and subjectivity displayed elsewhere. We’re still waiting for more of that.

Comments powered by CComment