- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: China

- Review Article: Yes

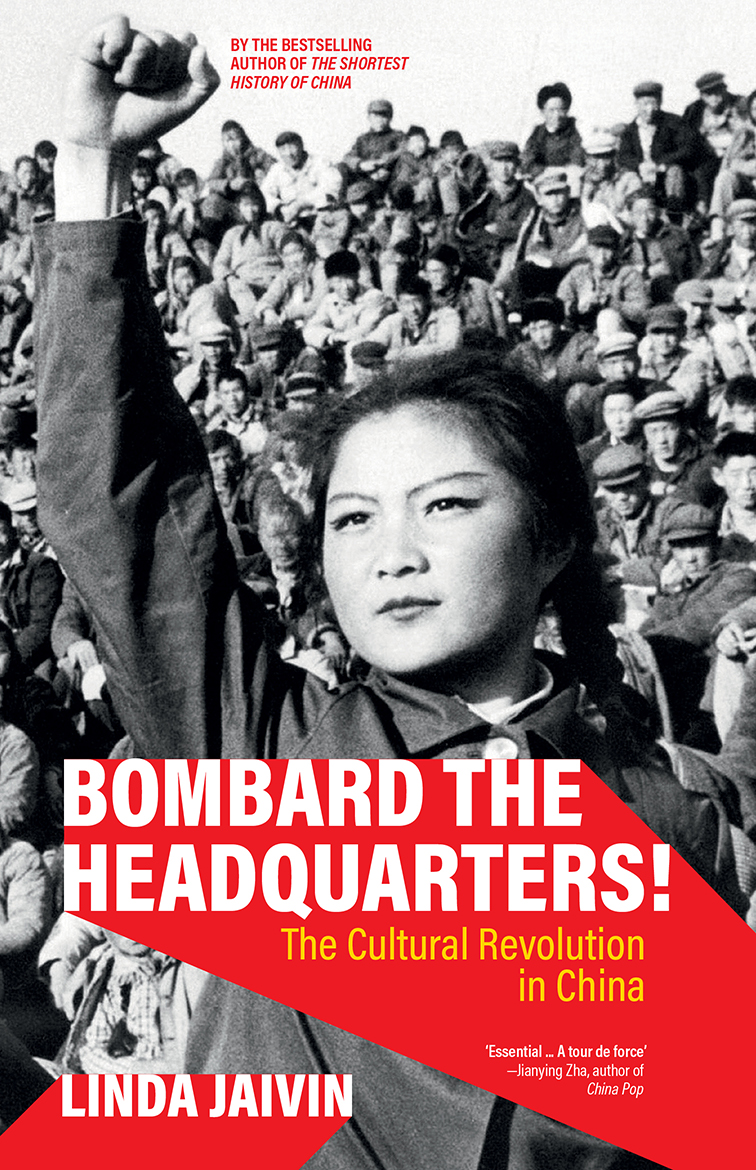

- Article Title: Mao’s mango

- Article Subtitle: Cultural Revolution as history or farce

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Of all the revolutionary regimes of the modern era, few sought to remake society as radically as Communist China during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Launched by Mao Zedong in 1966 to purge ‘class enemies’ and revitalise socialist ideals, the movement quickly spiralled into widespread upheaval that slipped beyond the Party’s control. Amid mass campaigns and brutal struggles, waves of political activism surged from below, jolting the very foundations of the Communist state and reshaping the country’s cultural and political landscape.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Shan Windscript reviews ‘Bombard the Headquarters! The Cultural Revolution in China’ by Linda Jaivin

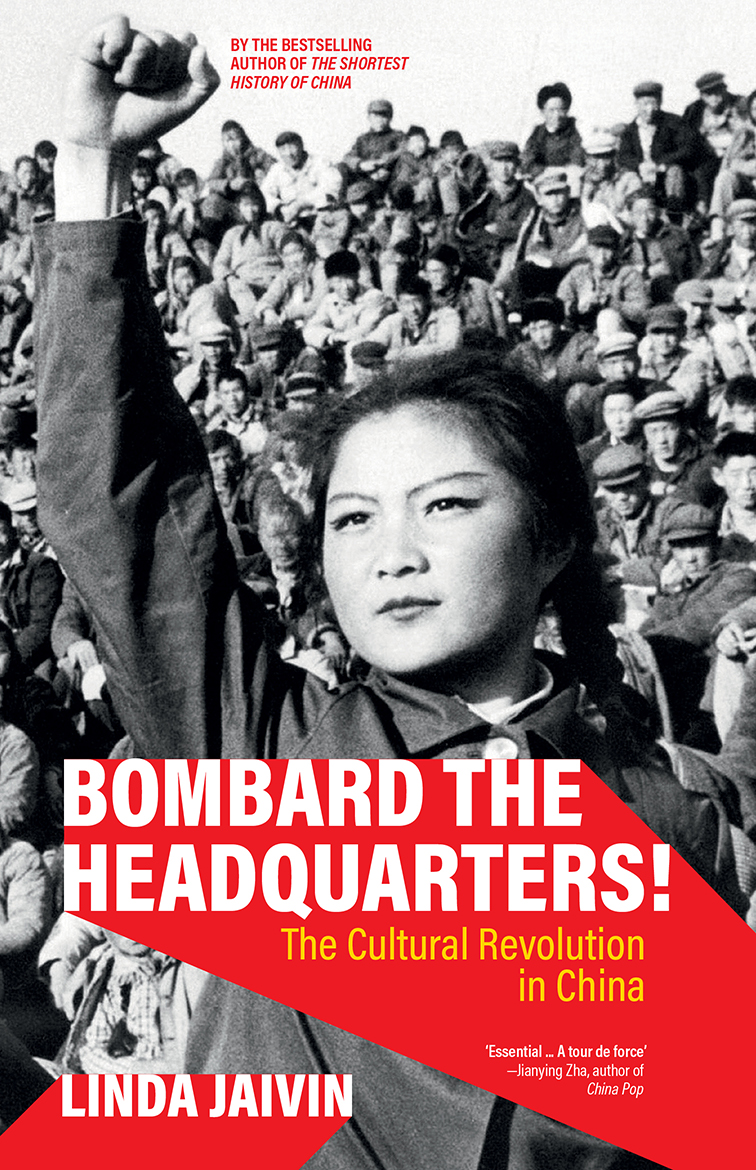

- Book 1 Title: Bombard the Headquarters!

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Cultural Revolution in China

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc, $26.99, 128 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781760645601/bombard-the-headquarters--linda-jaivin--2025--9781760645601#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

In Bombard the Headquarters!, the reader is drawn immediately into the charged political atmosphere of the Party’s inner chambers in early August 1966. Tensions have reached a breaking point. Mao, angry with moderate Party leaders for suppressing the unfolding Cultural Revolution, pens his iconic ‘Bombard the Headquarters’ big-character poster – typically a handwritten public display of political opinion, but in this case scribbled in the margins of a newspaper – calling for rebellion against entrenched ‘bourgeois’ bureaucratic power. This sets off, in Jaivin’s terms, ‘an explosion of political violence’ in the decade to come. Echoing the book’s title, this opening foreshadows Jaivin’s overall approach: a focus on Mao and other élite figures as the drivers of the revolution, the masses largely followers of directives from above.

Familiar patterns of violence, coercion, and intra-party power struggle run through the five ensuing chapters, charting key events of the revolution through often sensational accounts. Mao, sidelined after the disastrous Great Leap Forward (1958-1962) and the resulting famine, reclaims authority by unleashing mass political violence on his rivals. Among his agents (or pawns) are rebel youth dubbed Red Guards, whom Jaivin likens to frenzied ‘Monkey Kings’, a reference to Sun Wukong from the Chinese classic novel Journey to the West, who wreaks havoc in heaven. They beat and kill ‘class enemies’, denounce their own parents, ransack homes, and smash cultural relics, all in service of Mao’s radical vision.

By the book’s midpoint, existing social and political orders collapse, giving way to widespread purges, mass killings, factional violence, and border conflicts. Mao tries to rein in the chaos he unleashed, only to be met with mounting disorder, growing disillusion, and internal betrayal. When he dies, the Party reorients itself under new leadership, embracing economic liberalisation while suppressing open discussion and public commemoration of the Cultural Revolution.

Written in a conversational style, Bombard the Headquarters! succeeds in introducing a complex historical episode to a general audience. For casual readers, the book offers a concise and vivid account of the Cultural Revolution. More serious readers may be left wanting greater analytical depth and historical nuance.

Although Jaivin herself acknowledges the ‘convoluted’ and ‘confusing’ nature of the Cultural Revolution, this complexity is frequently undercut in the book by reductive moral judgements – that, for example, Mao simply ‘needed to signal who was boss’ or that he placed himself ‘above the law’. Meanwhile, phrases like ‘mass hysteria’, ‘mob of Red Guards’, and ‘a time of mob justice’ reduce the complex and varied experiences of rebel youth to images of unthinking violence.

The suffering and violence of the period should not be understated, but framing the Cultural Revolution as a descent into political madness – driven by a despotic Mao who manipulated a naïve youth movement – flattens historical complexity into a morality tale of power and victimhood. As recent scholarship on Maoist China has shown, the revolution was neither senseless nor reducible to élite power struggles. Rather, its violence and confusion reflected the Party’s struggle to navigate the dilemmas of state-socialism, as its leaders found themselves caught between aspirations for modernisation and fears of socialism’s degeneration amid unstable Cold War geopolitics.

Nor were ordinary people mere tools of a ruthless regime. As countless personal diaries from the era reveal, revolutionary identification coexisted with ambivalence and self-doubt. People took the movement seriously, not as passive subjects, but as thinking actors who negotiated meaning both within and outside of structures not of their own making.

Bombard the Headquarters! admirably lifts the lid on the Pandora’s box of the Cultural Revolution, only to collapse history into absurdity. This is reinforced in the book’s postscript, which relates the story of a Mao-era worker whose factory, during the Cultural Revolution, received a mango gifted by Mao as a political blessing. Wax replicas of the fruit were soon distributed to a workers’ meeting as a reminder of Mao’s love and endorsement. The worker told younger colleagues in recent years that she remembered feeling ‘incredibly grateful’ to be considered ‘a member of the revolutionary masses’, provoking their bemused responses: ‘It’s only a piece of fruit! People of your time! Really!’ In Jaivin’s book, revolutionary history risks appearing such a farce.

Comments powered by CComment