- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: ‘Balance sheet blues: The pros and cons of Pax Americana coming to an end’

- Review Article: No

- Article Title: Balance sheet blues

- Article Subtitle: The pros and cons of Pax Americana coming to an end

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The first six months of the second Trump administration have left American allies worldwide, including Australia, in a state of shock and sullen resignation. Shock at the resumption of Trump’s global trade and tariff war, following threats to Canada, Greenland and Mexico, not to mention the harm being done to American institutions and soft power; resignation that US protectionism and the rising demands of Washington on allies to pay more for their own defence are here to stay.

The Trump-Albanese meeting didn’t take place after the president left the summit early to take briefings on the Middle East crisis in Washington. Putting aside the howls of outrage from some commentators in Australia about this supposed ‘snub’, it now looks as if Albanese may have to wait until September to meet with Trump, when the prime minister travels to the United States for the UN General Assembly.

That is probably no bad thing given Washington’s preoccupation with – and direct involvement in – the Iran-Israel war, along with the sheer unpredictability of what might await Albanese in an Oval Office that has become not so much the place where warm sentiments about diplomatic relations are validated, but a capsule where visiting foreign leaders can be cornered and subjected to ridicule and humiliation. Just ask Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky and South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa.

To date, the Albanese government has navigated a sure, even guileful, path through the Trump hurricane. The Americans will not have missed Albanese’s repeated insistence that it is for Australia, not any other country, to determine its level of defence spending. Trade Minister Don Farrell, like Albanese, is standing his ground, rejecting calls from some in Washington to curtail Australia’s trade with China. For all Labor’s fidelity to AUKUS and its trepidation about being wedged on national security, the confidence that has come with a vastly increased majority in the federal parliament seems to have somewhat stiffened the Australian backbone.

But the problems of the immediate moment in handling Trump must not impede hard thinking about what this relationship is going to look like in future. There is unlikely to be a snap back in four years to the old American ally for which many in Australia yearn. The calls in Australia for a ‘more independent’ foreign policy grow ever louder. Amid a defence debate obsessed with statistics over strategy, a renewed focus on defence self-reliance is discernible.

Hugh White now talks of a ‘post-American’ future for Australia. But history would indicate that Australia doesn’t do end-of-empire moments particularly well. It panicked as Pax Britannica became less relevant and credible in the late 1960s. How will Australia fare as Pax Americana wanes? To start answering that question, it might be useful to compose a transactional balance sheet of the Australian-American relationship, if only to reveal how deeply woven that relationship has become into the strategic, commercial, and cultural fabric of this country. In particular, the policy of ‘alliance maintenance’, adopted by successive governments since John Howard, has become a de facto Australian strategy. It is going to take something extraordinary to dislodge it in the absence of obvious alternatives.

So, consider what Australia has done for the United States. It has integrated the Australian armed forces into the much more powerful US forces to the point where not much useful activity can now be undertaken by Australia independently. Australia, the loyal auxiliary of US forces, is ready to be taken in small contingents wherever the US military goes, offering a fig leaf or a UN vote where necessary.

The implication and probably the reality is that if conflict between China and the United States arose – presumably over Taiwan – Australia would be there, with little room to exercise sovereignty or an independent decision on whether it should be involved. One of the functions of deeper integration with US armed forces is to assist US military intimidation of China, and so the country has earned hostility in its biggest export market. This will endure, even if the Taiwan issue is settled peacefully.

Australia has assisted the United States in reassuring Japan, the Philippines, and Singapore that Washington wields effective military power in their neighbourhoods: in other words, it has contributed to the US pursuit of continuing primacy in East Asia. Canberra has helped preserve US influence in the South Pacific despite rising sea levels and the Trump administration’s contempt for action on climate change.

Successive governments in Canberra have maintained unwavering support for the United States even while Trump and other recent US administrations have sought to undermine the World Trade Organisation and the international trade rules-based order.

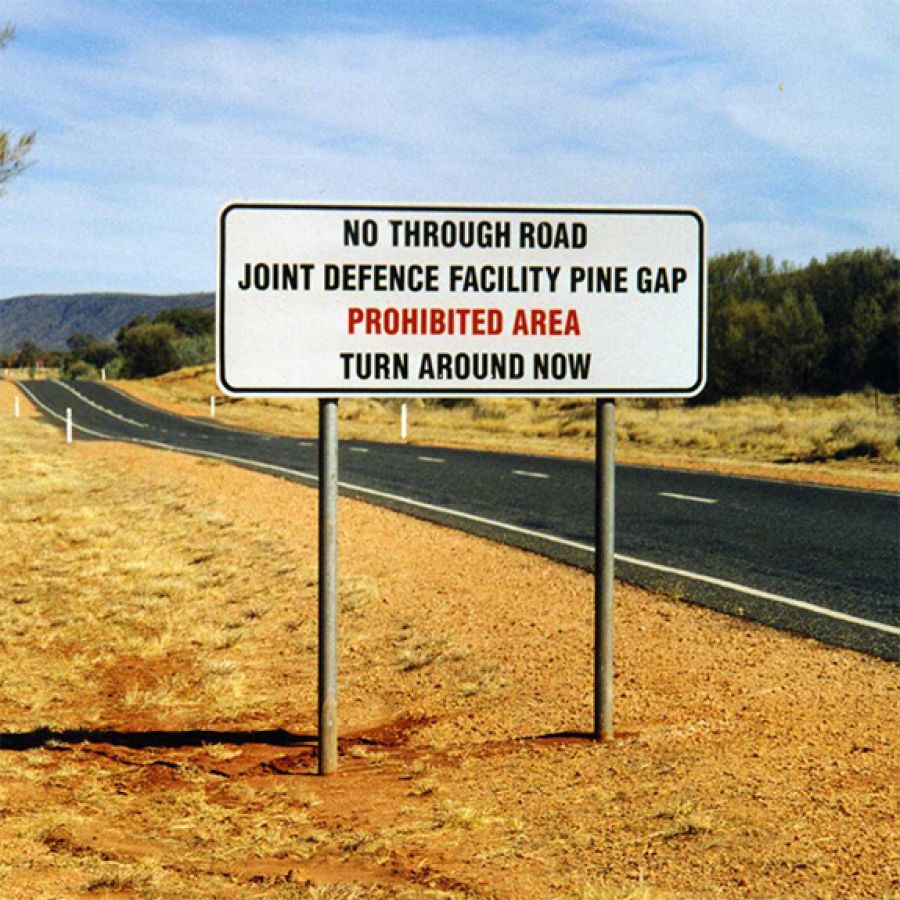

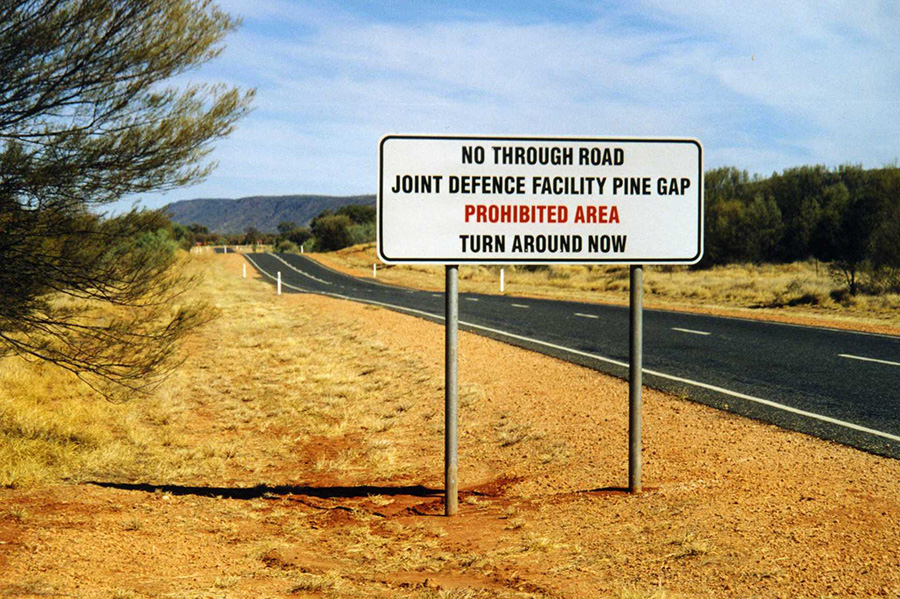

At Pine Gap, Australia offers a site still essential for US homeland defence against nuclear missile attacks, even though this makes Australia a nuclear target. Homeland defence tasks can now be diverted elsewhere but Alice Springs houses an essential intelligence gathering facility for war fighting for US forces. Elsewhere, HMAS Stirling, the navy’s primary west-coast base, situated just south of Perth, will become a nuclear target once it hosts nuclear-powered submarines, as required by AUKUS. In addition to hosting US marines in Darwin, Canberra has agreed to the stationing of B52 nuclear bombers at Tindal airfield in the Northern Territory. Most recently, Defence Minister Richard Marles made the first of a number of payments – this one for $800 million – towards the US nuclear submarine industrial base.

The road to the Joint Defence Facility of Pine Gap, near Alice Springs, 2006 (Schutz via Wikimedia Commons)

The road to the Joint Defence Facility of Pine Gap, near Alice Springs, 2006 (Schutz via Wikimedia Commons)

On the other side of the ledger, since 1942 the United States has provided Australia with psychological defences and reassurance over our fear of attack, a reassurance that was quite critical in developing an isolated white nation in the early postwar period and is probably still critical to many, if not most, Australians. The appearance of stability has also been important in establishing the secure investment climate that brought US, British and, later, Japanese and EU capital to Australia, essential foreign investment for Australian development.

Washington has also provided the weapons technology to arm Australia. Without US weapons, intelligence, training, and education, the question must be asked: could Australia operate its armed forces? Probably not. US naval power has offered implicit security to our sea lanes and trade across the Pacific and to Europe and Middle East markets; once again, it has provided something akin to investment climate protection. The United States has built a cultural affinity with Australia (as with many other countries) by including Australia in its intellectual and cultural world.

The realistic conclusion is that unless Trump disowns or undermines ANZUS, any abrupt breach with the United States would be very damaging to Australia.

An independent Australian foreign and defence policy, even if forced upon Canberra, would pose challenges, in some way or another, for foreign investment and the development of Australian industry and technology. And, in Australia and abroad, the likely interpretation would be that the country was home alone and vulnerable. To handle this issue domestically and in the international sphere, Australia would have to develop a new posture: at least mildly paranoid, ready for existential defence, and militarised to a significant extent. That is quite a different society and any move towards it would end our current relaxed style of government.

The idea that we need to ‘grit its teeth’, at least for four years, and be an even more ‘compliant auxiliary’ to the United States – for that defines much of the thinking in the Canberra national security establishment – is obviously designed with one objective in mind: to improve the chance of the United States helping Australia in a crunch. For some, this looks like increasing our spending on defence to five per cent of GDP, a major new commitment.

This is not the time for poking the United States in the eye, but it is most certainly not the time for getting on one’s knees to this mad king in Washington either.

Comments powered by CComment