- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Vienna has little to offer its great while they are alive. But when they have departed, a funeral monument and a place in the museum is arranged for them.’ So wrote the critic Oskar Marus Fontana, with veiled anti-Semitism, in a Munich periodical when the Wiener Wersktätte (WW) closed in 1932. From 1903 this famous Viennese design firm created innovative and finely crafted decorative arts, and fitted out modern interiors in concert with the major aesthetic philosophy shared by Secessionist artists, architects, and designers who worked under its banner in Vienna – the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). Swimming against tides of cultural, political, and economic change during the later 1920s, the WW was dissolved after its last ‘exhibition’ in 1932 – a large auction sale of more than seven thousand objects, many of which sold below their estimates.

- Book 1 Title: Vienna

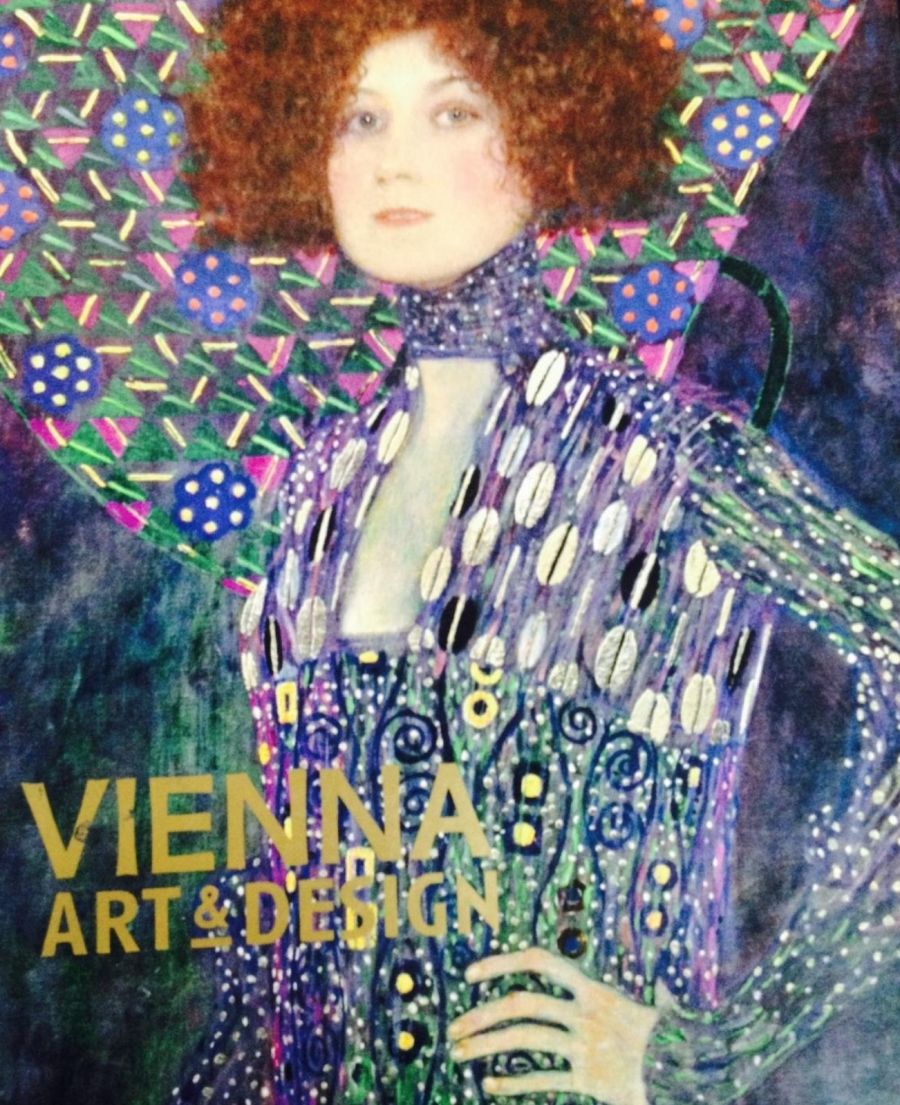

- Book 1 Subtitle: Art and Design: Klimt, Schiele, Hoffmann, Loos

- Book 1 Biblio: National Gallery of Victoria, $49.95 pb, 328 pp

The lavishly illustrated book that accompanies the exhibition Vienna: Art and Design, currently showing at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), puts paid to the above snide caricature of Viennese art and culture. Thematically arranged, the content illuminates the confluence of art, architecture, sculpture, furniture, fashion, ornament, glass, ceramics, jewellery, graphics, photography, dance, cabaret, music, and ideas that gave expression, emotion, and, above all, modern form and style to the vibrant city of Vienna predominantly between 1898 and the end of the once spawning Habsburg Empire in 1918 – the year of Gustav Klimt’s death. Illustrating the many generous loans from prestigious private and public collections across Europe and America, the book contains quality images of works from Australian collections and from the NGV’s significant holdings of avant-garde Viennese art and design. International and Australian specialists, and the Gallery’s curatorial staff, combine voices around chronological themes and provide, respectively, essays and entries about the period, its aesthetic and political tensions, and rich material legacy.

The legacies of yesterday’s tragedy can be tomorrow’s fortune, and so it was with the large collection of WW design, much of it created by Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser, and paintings including Gustav Klimt’s exquisite, idealised portrait of Hermine Gallia (1903–04), which made its way to Australia in 1938 after family members fled the Nazi régime. The sophisticated trappings of this wealthy Jewish family, bar Klimt’s painting, were later sold to the NGV, an acquisition acknowledging the contribution made to the arts in Australia by European refugees. Tim Bonyhady, an Australian descendant of the Gallias, shares his research into the collection’s formation and display in Vienna, and concerning Hermine Gallia and her husband’s milieu of artistic patrons who sought individual distinction apart from the old aristocratic order. Illuminating essays interpret the works from the NGV’s collection, including the meditation on George Minne’s spiritually taut sculpture, Kneeling youth (1898), which influenced the sensuous, confronting nudes of Klimt, and Egon Schiele’s erotica. One might add the linear, graphic nudes of Oskar Kokoschka published in his artist book, which celebrates youth and dreams by the WW between 1907 and 1908.

If Nikolaus Pevsner once championed the ‘true pioneers’ of the modern movement as those ‘who from the outset stood for machine art’, Christian Witt-Dörring reflects here on Vienna as a major source of inspiration for postmodernism’s play on historic continuum. Emphasising the rise of the individual in this urbanising, modernising city, Witt-Dörring identifies the ambiguous relationship between emotion and rationalism and between the subjective and the objective, and emphasises that the characteristics of Viennese art and architecture at the turn of the twentieth century resist classification according to the canonical criteria of modernism. A case in point is Adolf Loos’ designs of English eighteenth-century revival furniture for the Langer apartment, spatially defined by its restrained functional aesthetic. As some of the essays and entries suggest, the form follows function aesthetic manifested radically in the latticed and gridded vases and fruit boxes, and other early metal work of the WW, and in creative tension and paradox, as in objects influenced by Dagobert Peche, the designer and manager of the artists’ workshops from 1915. Yet the function of an object could be its decorative appeal, as seen in Michael Powolny’s delightfully jeunesse ornamental ceramics. At other times, decoration articulated architectural rhythm, as in the repeated sunflower motif on Karlsplatz Station, Vienna, designed by Otto Wagner (1894–1902), popularised by the English Aesthetic movement, and adopted by Siegfried Bing for the façade of his Maison de l’Art Nouveau in Paris in 1895. Indeed, the subtitle of this book, listing four of the major individuals it presents, Klimt, Schiele, Hoffmann, Loos, suggests the tensions across their works: functionality and ornament, planar geometry, line and rhythm, Freudian psycho-sexuality and primitivist urges, and simple, smooth, or embellished surface decoration.

‘To the age its art, to art its freedom’ was the motto of the new Secessionist building designed by Joseph Maria Olbrich and opened in 1898. An audacious antidote to the historicising grandeur of the neo-Renaissance and neo-Gothic architecture of Vienna’s Ringstrasse and the deadening art of the Academy, the geometric form of Olbrich’s temple of art was crowned with a large dome of interlacing gilded leaves. This building was the resplendent symbol of cultural and artistic rejuvenation, which the Secession, founded by Olbrich, Klimt, Hoffmann, Moser, and others in 1897, was determined to achieve. The flowering of this new spring, epitomised by the title of the new Secessionist art journal Ver Sacrum (Sacred Spring), issued regularly between 1898 and 1903, was extraordinary, and the local and international art exhibitions brought together by the Secession inspired Viennese art and design. As the book reveals, Viennese art and culture were replenished by aesthetic assimilation; Japanese arts, leaders of the Arts and Crafts movements in England and in Scotland, late Art Nouveau, French Impressionism and post-Impressionism, divisionism, and currents of European Symbolism synthesised into refined and unique expressions of art and design.

The scintillating, mosaic-like colour surfaces of Klimt’s closely framed landscapes, and his visual hymns to female beauty, are immediately recognisable today. But this book exonerates his art from a singular iconic status. It collaborates with architects and other artists, and reflects the desires of his patrons, who sought individuality within the élite echelons of the haute-bourgeois and predominately secular Jewry of Viennese society. Among the many revelations in Vienna, there are a few surprising omissions. The influence of the early nineteenth-century Austrian Biedermeier period on some of the geometric designs produced by the WW, and the neoclassically styled Viennese domestic interiors, is identified, but there is no mention of Schubert, whose music was a part of the earlier period’s Zeitgeist. Schubert plays the piano in Klimt’s incandescent sopraporta mural at Immerdorf Castle, in Southern Austria, which the Nazis detonated in 1945, destroying all of Klimt’s art inside; the composers Beethoven, Mahler, and Schoenberg otherwise add to Vienna’s new cultural spirit. The influence of the Anglo-American painter James McNeill Whistler is glossed over in the text, which is surprising, because Klimt and Whistler regularly corresponded. Klimt was invited to exhibit in London in 1898, and they shared aesthetic convictions about the way art should be framed and exhibited. Whistler’s atmospheric Aestheticism resonates in Klimt’s Hermine Gallia, in which painterly impressions of silken materials fabricate her reform dress designed by the artist. Klimt’s use of Friedrich Schiller’s dictum, ‘If you cannot please everyone by your actions and your art – please the few well. It is not good to please the many …’ echoes Whistler’s privileging of art’s autonomy above social realities. But Klimt moved this philosophy to a completely different register through his emotionally charged ornamental paintings.

Apart from the images and discussions about Emilie Flöge, Klimt’s companion and muse who established the stylish fashion house with her sister in Vienna, the section of WW fashion is thin. No mention is made of the French couturier Paul Poiret, who purchased many WW abstract textile patterns before World War I and established his own interior-decorating studio in Paris under its workshop’s influence. Design histories separate the WW into the ‘geometric’ and ‘form follows function aesthetic’ before World War I and the baroque decorative expressions designed after this war and into the 1920s. Dagobert Peche’s filigree jewel box, a fanciful mirror frame, and his fantastic walnut writing desk epitomise this swing in the book, but several photographs of fashions designed by Eduard Wimmer-Wisgrill would costume this change.

Another coup for the National Gallery of Victoria, this brilliant exhibition book contributes to the international appreciation of Viennese art and design at the turn of the twentieth century. A specialist, accessible, and handsomely illustrated volume that entertains with its probing perspectives and lucid commentary, Vienna: Art and Design keeps the period and its arts alive, and enriches scholarship on this leading early twentieth-century modern movement.

CONTENTS: JULY–AUGUST 2011

Comments powered by CComment