- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Journalism

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

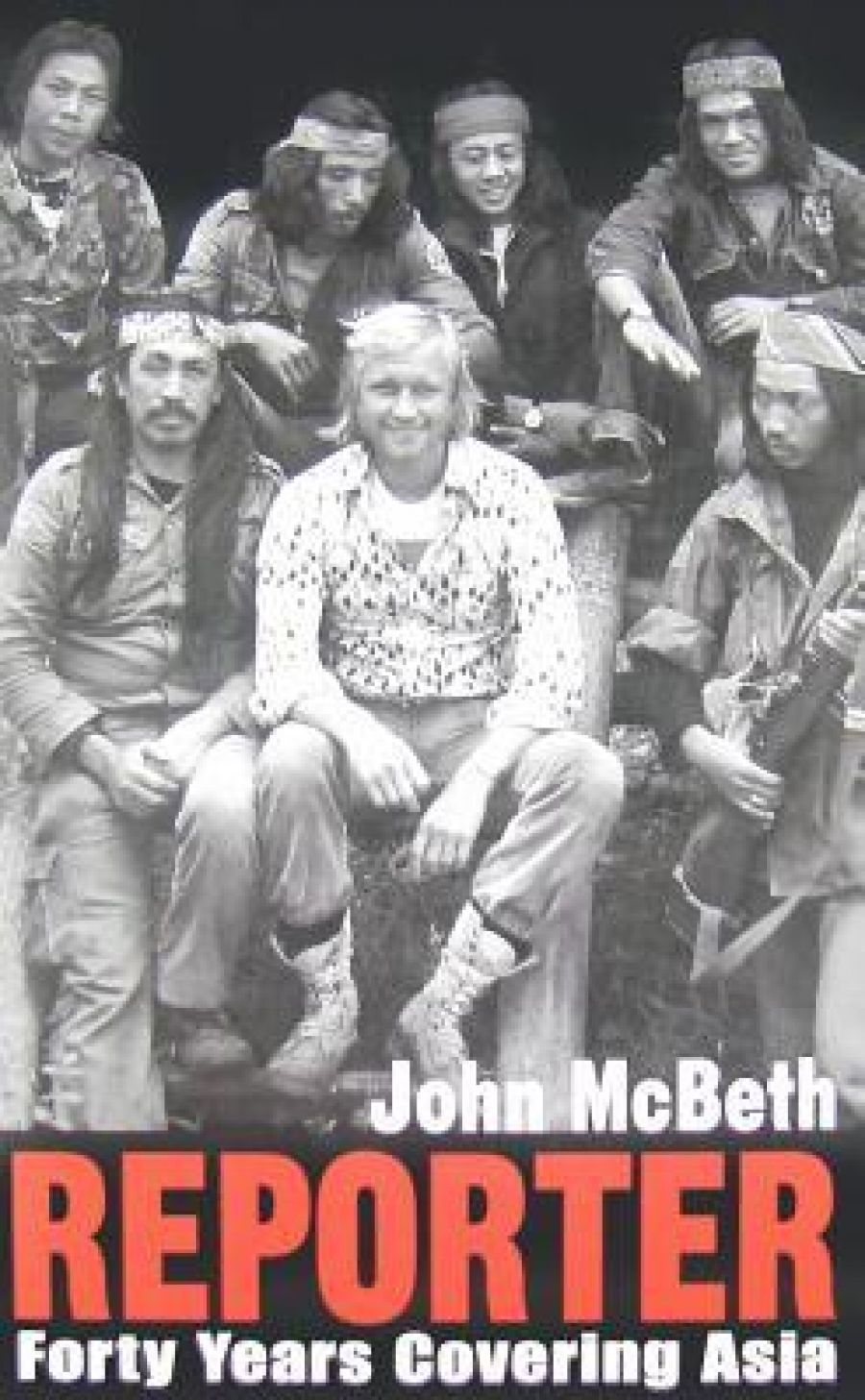

From childhood on a dairy farm in the flats beneath Mount Egmont, in New Zealand, John McBeth rose to become a senior foreign correspondent with the Far Eastern Economic Review, one of Asia’s most influential English-language news magazines. Like other old-school journalists, he asserts at the beginning of his highly entertaining memoir that no one can be ‘taught’ journalism; you are either born one, or not. So it proved in his case. A liberal arts education might have made the younger John a more reflective autodidact, but possibly not a more successful journalist.

- Book 1 Title: Reporter

- Book 1 Subtitle: Forty Years Covering Asia

- Book 1 Biblio: Talisman Publishing, $42 hb, 384 pp

McBeth cut his teeth at the Taranaki Herald and Auckland Star. He decided to make his home in South-East Asia when a boat carrying him to England ran aground in Jakarta in 1970. He lived rough in Bangkok and worked for the Bangkok Post. He wrote about the heroin trade along the Thai-Burmese border; a hotel fire where the brigade refused to turn on the hoses until it had negotiated a satisfactory payment for its services; and a Cathay Pacific airline crash in which the patently guilty bomber escaped scot-free on a legal technicality. McBeth followed the peregrinations of the French-Vietnamese serial killer, Charles Sobhraj, was an extra in Michael Cimino’s Vietnam War film The Deer Hunter, and befriended Jimmy Smedley, the drug-dealing American owner of a funky Afro-American bar off Petchburi Road.

McBeth, in 1975–76, reported on the desperate wave of refugees that washed across South-East Asia at the end of the Vietnam War, the Thai fisher/pirates who raped and murdered Vietnamese boat people, and the Thai soldiers who forced Cambodian refugees back into a Khmer Rouge minefield instead of allowing them to enter Thailand. These were part of Thailand’s strategy of discouraging the influx of refugees. Altogether, McBeth covered five coups in Thailand, travelling everywhere by public transport.

In Bangkok, in 1979, McBeth joined the Far Eastern Economic Review. The following year hetransferred to Seoul as bureau chief. He wryly observed that in contrast to the Thais, the Koreans were intensely physical without having a sense of personal space. In crowded urban streets, McBeth’s rugby training served him well.

McBeth’s rich store of anecdotes in Seoul included tales of North Korea’s attempted assassination of President Chun Doo-hwan in the Rangoon bombing of August 1983; the surreal theatre between North and South Korean officials in the negotiating hut at Panmunjom; the arrest and trial of the pretty young North Korean spy Kim Hyun-hui, who helped bring down a ROK passenger aircraft over the Gulf of Mataban in November 1987, later became a Christian, and married her South Korean bodyguard; and the spectacular 1988 Seoul Olympics. McBeth claims that his best scoop came from this reviewer, who in late 1988 tipped him off about North Korea’s secret nuclear program, a story which, to McBeth’s chagrin, sank like a stone when the Review published it.

In meticulous detail, McBeth documented the untidy and contentious transition in Korea during the 1980s from military dictatorship to democracy, and the street theatre between security police and university students that accompanied it. He calculated that $US6.7 million worth of tear gas was discharged on the streets of Seoul in the first nine months of 1986 alone.

Two more postings followed McBeth’s stint in Korea: first to the Philippines at the end of the 1980s; and then to Indonesia. In Manila, in 1989, he wrote a richly detailed series of articles for the Review, analysing the reasons for the Philippines’ continuing economic malaise at a time when other countries in the region were beginning to prosper. He observed that nine million Filipinos – ten per cent of the population – were forced to head overseas for employment because a powerful and selfish élite had insufficient vision to employ them in home-based industries. McBeth observed that a thin veneer of democracy overlay a deep system of feudalism, reinforced by the Catholic Church, which stifled any sense of entitlement in the rural society. In his view, the overthrow of Ferdinand Marcos in the popular coup of 1985 and the subsequent installation of Corazon Aquino as president had changed nothing.

1991 was the year of the volcano – and of McBeth’s right leg. The volcano was Pinatubo in central Luzon, which erupted in March and buried the surrounding countryside in ash, including Clark, a large US Air Force base east of the volcano, and Subic Bay, a major repair base for the US Seventh Fleet. Both of them were permanently evacuated by United States armed forces. Meanwhile, McBeth’s leg began to deteriorate from gangrene attributable to his heavy smoking (he was a three-pack-a-day man). After a string of fruitless angioplasty procedures, it was surgically removed in 1992.

In the early 1990s McBeth became the Review’s bureau chief in Jakarta. He arrived there at a time of growing social unrest due to a widening gap between rich urban dwellers and the rural poor, a depletion of agricultural land in Java, poor income distribution engendered by twenty conglomerates controlling eighty per cent of the country’s top 400 companies, and a predisposition of city dwellers to believe that rural dwellers could not think for themselves. McBeth chronicled growing tensions between President Suharto and some of Indonesia’s top politicians, and increasing social disturbances, including anti-Chinese riots and troubles in West Kalimantan, which preceded Suharto’s relinquishment of power to B.J. Habibie in 1988.

McBeth believes that his best writing about Indonesia was inspired by the thoughts of four wise Indonesian friends: a diplomat turned shipping magnate; a former foreign minister; an oil executive; and an academic who advised Suharto on social issues. They did not blame Sukarno or Suharto for Indonesia’s 2002 financial meltdown so much as the oppressive Javanese culture, bureaucratic nepotism, a commercial licensing system that bred a generation of rent-seekers, and the residue of Dutch culture, which was expert at training mechanics and technicians, but not managers or political leaders. Notwithstanding these weaknesses, the Indonesians have a single language, many shared values, and a sense of nationhood. Indonesian students abroad, McBeth observes, usually return. Filipinos often do not.

McBeth’s most poignant observations concern the death of the Review, which was finally closed in 2009. Along with Asiaweek, it used to be read for its insights into local politics by every English-speaking diplomat and business person in the region. After its acquisition by the giant Dow Jones empire in the early 1990s, it was commercialised, downsized, and trivialised by an arrogant American management team unfamiliar with Asian cultures and values. Asiaweek was killed off in a similar way by Time-Warner.

McBeth belongs to a small club of foreign correspondents who, by way of thorough investigation, made sense of events in Asia during the tumultuous 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. No current English-language television – not CNN, the BBC, or Al Jazeera – can do this. In the nightclubs of Patpong, one could still hear echoes of the raucous and intensely competitive expatriate scribes – such as Neil Davis, Paul Lockyer, and Geoff Leach, all Australians – as they boasted about their latest scoops. Two passionate and intelligent Kiwis graced their company: Kate Webb, the UPI correspondent who spent twenty-three days in Viet Cong captivity in 1971, and John McBeth. His book should be compulsory reading for every student of media studies in the English-speaking world.

Comments powered by CComment